While clicking the heels of her ruby slippers near the end of “The Wizard of Oz,” the character Dorothy Gale voiced the famous movie lines “There’s no place like home. There’s no place like home.”

It’s generally assumed the words in the 1939 musical mirror the book “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” published in 1900. But L. Frank Baum’s actual words were: “No matter how dreary and gray our homes are, we people of flesh and blood would rather live there than in any other country, be it ever so beautiful. There is no place like home.”

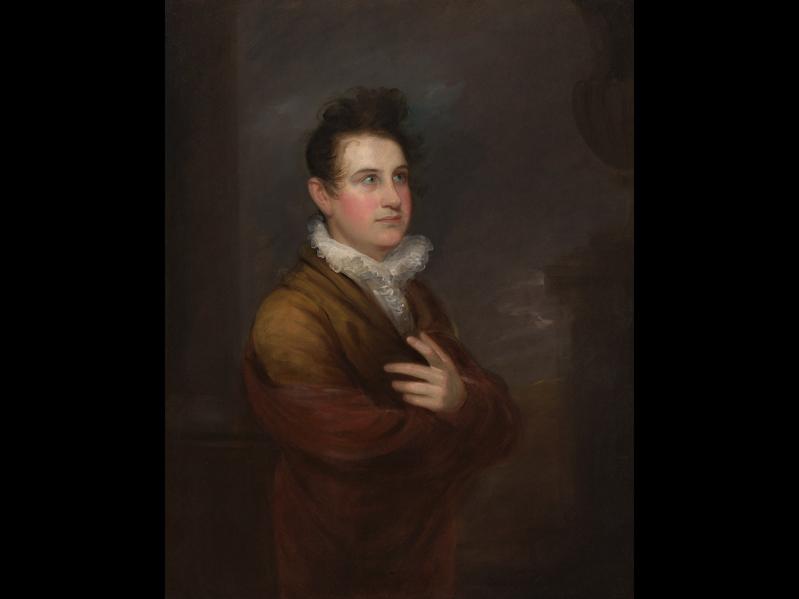

The earlier origin of “There’s no place like home” dates to 1823 — 200 years ago — when the playwright, actor, and lyricist John Howard Payne (1791-1852) premiered the song “Home Sweet Home” in Paris for the operetta “Clari, the Maid of Milan.”

Unlike Baum’s stiff writing, Payne’s chorus was a heart softener, pulling out all the sentimental stops. What seems to be a constant in its many adaptations are these core words: “ ’Mid pleasures and palaces, where’er we may roam, / Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home / . . . Home! Home! / Sweet, sweet home! / There’s no place like home, / There’s no place like home.”

Payne’s parlor ballad, set to music by Sir Henry Bishop, became the most popular song in the English-speaking world of that era.

The idealized tribute to home life was easy to sing and remember. Decades after the 1823 premiere, the melancholy tune was still quite popular. Charles Dickens during his American tour of 1842 confided that he played it on his accordion every night with “great expression and a pleasant feeling of sadness.”

Although copyright laws back then precluded great monetary gains, Payne was rewarded with a taste of fame for “Home Sweet Home.” Two years before his death, for example, the songwriter and thespian — also known by the sobriquet “America’s Hamlet” — was in the audience when the Swedish soprano Jenny Lind sang his composition in Washington, D.C., on Dec. 17, 1850. The crowd included President Millard Fillmore, Secretary of State Daniel Webster, and Senator Henry Clay. Before her encore, according to a recounting of the evening in Hall’s Journal of Health, Lind turned in the direction of Payne, and “people of the undemonstrative sort clapped, stamped and shouted as if they were mad, and it seemed as if there would be no end to the uproar.”

The acclaim for “Home Sweet Home” continued through the Civil War. Among the devoted fans were President Abraham Lincoln and his wife, Mary, who in 1862 after the death of their son Willie invited the opera star Adelina Patti to perform it at the White House. She later serenaded Queen Victoria with the tender song at Windsor Castle. (A remaster of Patti singing “Home Sweet Home” is available on YouTube.)

What the rootless Payne, who moved to Europe at age 22 and stayed abroad for 20 years, considered “home” has been the subject of debate. East Hampton was formerly cited as his birthplace, with good reason. His ancestors were founders of the town, and his father and mother were educators at Clinton Academy. Payne’s birthplace is more likely to be Pearl Street in Manhattan, according to an 1872 report from a committee investigating the origin story.

Brooklyn has considerable reason to claim him as well. His brother Thatcher and adored niece, Eloise Elizabeth, lived in the Clinton section of Brooklyn. The famously impecunious Uncle Howard, who was jailed in London’s Fleet Prison for debts and used the quiet opportunity to write another play, stayed with them often, particularly when money was tight.

In September 1873, the city of Brooklyn demonstrated its affection for Payne with a turnout of an estimated 6,000 citizens to an unveiling of his 17-foot statue at the crest of Sullivan Heights in the newly opened Prospect Park. The Faust Club, a short-lived arts and social group, stayed organized long enough (1872-1875) to commission the “bright bronze bust on a highly polished granite pedestal” to honor Payne, whom members considered a founder of the American theater.

A more peaceful “homelike spot can scarcely be imagined,” said Gabriel Harrison, the club’s president. The spot is within walking distance of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, which today houses the botanical artwork of Payne’s grand-niece Eloise Payne Luquer.

A decade after the unveiling of the monument in Brooklyn, the art collector William Corcoran, who as a boy had watched the handsome Payne perform, paid for the remains of the actor-songwriter to be exhumed and shipped from Tunis (Payne was a consul there) to New York. After a “unique and dramatic” cortege in Manhattan, Payne lay in state at City Hall, then traveled by special railroad car to the nation’s capital.

On June 9, 1883, precisely 92 years after his birth, John Howard Payne was reinterred in Oak Hill Cemetery. Troops from five military companies “were in line along the avenue in front of the Corcoran Gallery,” according to the Faust Club’s Harrison, who was an eyewitness and Payne’s biographer. One hundred “voices of the Philharmonic Society” sang “Home Sweet Home.” The full U.S. Marine Band led by John Philip Sousa played before an audience of 2,000 people.

Congress was adjourned to attend the funeral. The stately procession accompanying the coffin included foreign diplomats, members of the cabinet and Supreme Court, and President Chester A. Arthur. In the heart of it all, between the pallbearers and the president, were John Howard Payne’s relatives Eloise Elizabeth Payne Luquer, his only niece and sole heir, and her husband, the Rev. Lea Luquer of Bedford, N.Y.

Payne’s tombstone in Washington endures. Alas, the object of admiration in Brooklyn would have a restless fate like its subject. In 1974, vandals covered the Prospect Park bust in graffiti. The once-proud monument on the hill, a scrawled-over eyesore, was removed and languished in storage for more than 25 years.

It was given a careful scrub, and found a more fitting place of repose in 2001. “We have the head,” assured Hugh King of the Home, Sweet Home Museum in East Hampton.

“ ’Mid pleasures and palaces, where’er we may roam, / Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home.”

Judy Culbreth is the author of “Bedford Garden Club Originals: New York’s Eloise Luquer and Delia Marble,” just out from the History Press.