During the long buildup to the Paris 2024 Olympics, I began to feel a vague sense of unease at the prospect of millions of athletes, organizers, and spectators swarming that beautiful, magical city.

Yes, the Olympics are special but Paris is . . . well, Paris.

I worried for naught. The Olympics did not overtake Paris. Indeed, Paris took over the Olympics. There were bumpy moments, to be sure. Rain pelted the opening ceremony, the Seine was briefly corrupted with bacteria, and an agitator sabotaged the railway at dawn on opening day.

Undeterred, Paris proceeded to present an Olympic Games that were fully Olympian but also reflected the soul of a 21st-century Paris. Sophisticated technology kept the mechanical aspects humming while imaginative designs suffused every venue with an artistic flavor.

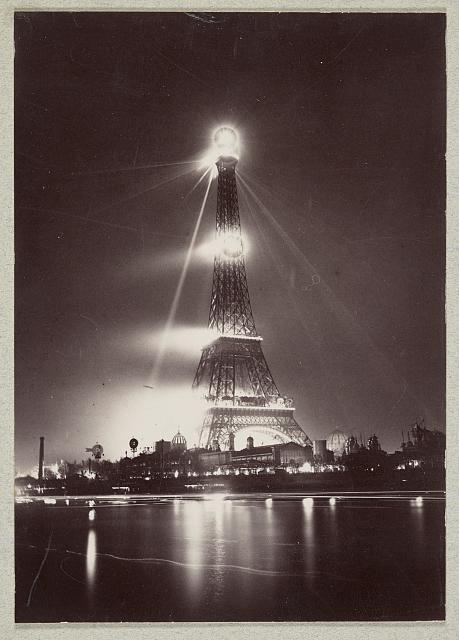

Outdoor events were in full view of gorgeous buildings, vibrant greenspaces, and, of course, the River Seine. NBC’s go-to image every night was the twinkling Eiffel Tower. Commentators reported from sidewalk cafes, quaint side streets, and the winding walkways along the Seine.

These glimpses of Paris awakened memories of my first visit. It was 1970 and I was a 20-something living in New York City, eager to travel. I had saved enough money to quit my job, pay three months of rent in advance, and finance my adventure. I felt it was then or perhaps never. A romantic relationship was getting serious and my unencumbered days seemed to be dwindling.

The game plan was simple. Once Icelandic Airlines deposited me in Brussels, I planned to travel all over Europe by train, finding places to stay within walking distance of the train station. I hoped to eventually make my way to Beirut, where a cousin managed the InterContinental Hotel.

Paris would be my first destination.

I found a small pension a short walk from the station. It was run by a family — mother, father, and a daughter probably in her 30s. The room, including breakfast, cost the equivalent of $3.98. I was in Chambre 15 on the second floor.

My first morning I headed downstairs for breakfast and sat alone at a small table. The daughter approached and, in French, asked for my room number. I had studied French for only six weeks before leaving the U.S., but I knew the numbers up to 20.

“Quinze,” I said, smiling and confident.

She frowned and repeated the question in English.

I sheepishly replied, “Fifteen.”

It was the first of many times that I felt so utterly un-French. I would see French women effortlessly wear the simplest clothing with amazing style. French men seemed to project a piercing, sensual look even when simply handing me a croissant in a busy bakery.

The next day we repeated the routine. She asked in French, I answered in French, and after pausing to frown, she repeated it in English. This continued for a number of days. Finally, one morning, after I said “quinze” as confidently as I could muster, she paused and gave me a curt nod.

This was puzzling. Was my French suddenly understandable? It couldn’t be that. Instead, I sensed that she wanted me to “be there” and not just a visitor looking “at” her. And in that moment I did feel the difference. Our awkward interactions had led me to actually being there. In all my years of travel since then, I strive to be there no matter where I am.

For the rest of my stay, she didn’t ask for my room number. We exchanged greetings and sometimes there was a hint of a smile.

Meanwhile, all of Paris beckoned.

With so many museums, ancient churches, and monuments seemingly on every corner, it was overwhelming. The first day, I set out with a list of must-see attractions and map in hand, but after several hours I escaped to a leafy riverbank along the glorious Seine. A young man approached and gestured a desire to sit near me. I nodded and soon we were deep in conversation — thankfully in English.

He looked remarkably like Yves Saint Laurent — tall, slim, with a full head of wavy hair and wide-rimmed glasses. His name was Emile and he worked in the Paris office of the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency.

He invited me to dinner and that evening I sat at a table with Emile and a half-dozen of his friends, both men and women, everyone jovial and pleasant. The conversations were in French, and while Emile would translate here and there, I was happy just to be there and soak in the sounds and faces, the food and ambience of the cafe.

We had an instant connection, somewhere between friendship and romance, and met every day after he finished work. Emile was proud of his city and wanted me to know the Paris that he loved.

His enthusiasm was a powerful incentive and transformed me into a Super Sightseer. I set out early each morning determined to see it all. I spent nonstop hours taking in art and architecture, gardens and bridges, all over Paris. I just couldn’t disappoint Emile when he would eagerly ask, “What did you see today?”

As a novice tourist, I learned it was permissible to walk through a room of paintings and not pause unless captivated. And then I would stand motionless and fully immersed, embracing the visceral experience. I learned to take the unexpected detour if a monument, shop, or garden beckoned while I headed from one destination to another.

Those days were exhilarating, but seeing Paris at night with Emile was intoxicating. The street lamps were dreamy, softly illuminating the winding back streets and cozy cafes. At dinner, we would talk about the hopes, fears, desires, and ideas that swirl in your head but are never shared with your family or friends. It was an intimate, wondrous relationship without a romantic involvement.

After a whirlwind week, it was time to leave Paris. My next stop was to be Monte Carlo, timed so I could be there for the Grand Prix auto race. It was surreal to say goodbye to Emile, and I could feel more than a twinge of sadness.

He asked if I might be returning to Paris.

Maybe, I said.

Karen Lane is at work on a true-crime book. She lives in Montauk and New York City.