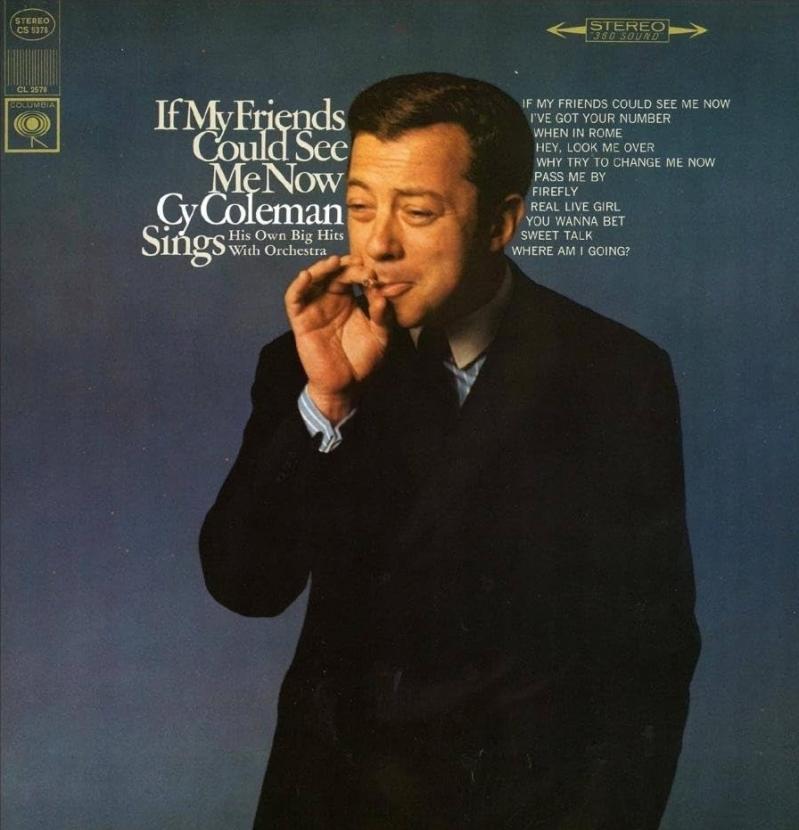

The celebrated Broadway and pop composer Cy Coleman (“Witchcraft,” “The Best Is Yet to Come,” “If My Friends Could See Me Now”) died nearly 20 years ago. But Grammy Week (he won two and was nominated countless times) and the recent release of his best songs on CD (“A Collective Cy: Jeff Harnar Sings Cy Coleman”) bring back memories of seeing him in the Hamptons and in Manhattan in the 1970s. Something fun was always about to happen. And did.

“Wouldn’t you like to have fun, fun, fun / how’s about a few laughs, laughs / I could show you a good time” — from “Big Spender,” which appeared in the musical “Sweet Charity” by Cy and the lyricist Dorothy Fields in 1966. My fave show before and after I knew him.

I met Cy in the Upper East Side office of Dr. George Serban, the brilliant Romanian head of the Society for Existential Psychiatry and an N.Y.U. clinical professor. My shrink. Cy’s, too. Everyone had one. Cy checked in once a week forever with George, his most trusted business and life adviser.

I was coming, Cy going, and we began to talk. He asked for my phone number — a big no-no. George disapproved of patients mingling. He kept it private, on a first-name basis only. Cy called anyway: illicit, irresistible.

Our first date was at Elaine’s, prestigious table number two, just us. He was quite the character — comedian, a quintessential Gemini chameleon, upbeat like his music. Adorable apple cheeks, protruding lower lip, mischievous smile, a tad chunky. A cockeyed optimist and fascinating conversationalist, he loved wordplay. We clicked.

One by one the regulars came by. Everyone loved Cy; they wanted to catch some stardust. He had two musicals on Broadway at the same time, “I Love My Wife” and “Barnum,” no mean feat — never so much the book and lyrics but his sparkling scores.

We’d return often to the Fat Lady’s (as she was known behind her back), dine with Jimmy Lipton (host of “Inside the Actors Studio”) and his wife, Kedakai, or alone, never for long.

Cy worked on multiple projects. In 1974 he co-wrote Shirley MacLaine’s one-woman, one-hour TV special, “If They Could See Me Now,” Shirley a constant presence, how it often goes with such collaborations. Cy, a nimble jazz pianist, played and sang with her for a private musicale at the apartment of Cy Feuer (director of Cy Coleman’s “Little Me,” producer of “Guys and Dolls” and the film “Cabaret”).

Shirley looked chic in a Ralph Lauren brown corduroy maxi dress and long nails. Cy introduced us. I got the cold shoulder, relegated to “Why should I bother with another in a series of Cy’s girlfriends?” It was a long list; he was the most eligible bachelor in town for decades.

Cut to a double date at the popular Trader Vic’s under the Plaza Hotel months later with Shirley and her then-beau, the author, columnist, and editor Pete Hamill. Cy was in heaven, holding court, and Shirley was again ignoring me — Cy didn’t notice — as she got drunk (who wouldn’t) on two notorious Scorpions, bowls of a toxic concoction served with a gardenia on top.

“Do you mind taking her to the ladies’ room?” Cy prompted. What could I say? I was stuck, her reluctant caretaker and cleaner-upper.

Out this way, Cy’s ramshackle beach house on Dune Road in Southampton had a Fire Island feeling. A blue-and-white-striped old-fashioned swing was on the front porch, inside nothing much matched. No woman had lasted long enough to pressure him into interior redecorating (until he found Shelby Brown in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, and married her late in life).

He came out on weekends all year. We’d go grocery shopping first, Cy in one of his comfy “country” outfits — T-shirt and Bermudas, funky hat, while he was always dressed to the nines in the city. He pushed a filled-to-the-gills cart, enough food for the rest of the summer, including junk food and cookies, Mallomars, Fig Newtons, chocolate chips. He had a sweet tooth.

Food stashed, we changed into bathing suits, walked down a narrow path at the top of the dune, his private entry to the beach, the ocean, a dream location.

“Last one in is a rotten egg!” He went right in regardless of the temperature. I was always the last. He wore a bathing cap to protect his toupee, which was never mentioned, ever.

Cy was always game for games. We played tennis at a friend’s court down Dune Road, both of us in whites. He had a wood Wilson Jack Kramer; mine, a metal Wilson T2000, same as Jimmy Connors.

Cy’s tennis was like him, surprising; his slices dropped dead, to his glee. My strokes were better, which didn’t always matter. Ron Mallory, an artist who worked in mercury, Cy’s best friend, joined us for Australian doubles. They laughed as they made impossible shots, everyone extremely competitive. When they sometimes beat me, Cy teased about how “old men out of shape, playing tennis once in a blue moon, can massacre you and your metal racket.” Take that.

The Hamptons were then home to a host of authors who congregated at night at Bobby Van’s, a dark bar founded in 1969 in Bridgehampton. Later occupied by World Pie after Bobby moved across the street. He played the piano drunk, and it was the pits. James Jones, Kurt Vonnegut, Truman Capote, Willie Morris, and Winston Groom hung out. Cy hated it: “bad food, worse music.”

After lots of drinks, Cy and I discussed a project we’d been bantering about, making a musical of “An Unmarried Woman,” the film with Jill Clayburgh — how a happily married woman’s husband leaves her after meeting a woman at Bloomingdale’s. I’d found a copy of the script. We could buy the rights and call it “Unmarried.”

On the spot he offered to write the music if I wrote the book and lyrics. Me? I was overwhelmed. I wrote one song, a tango, that went, “I had an encounter at the counter of Bloomingdale’s.” Then I petered out, 30-something and lacking confidence. “If only” is all I can say. It’s one of the great regrets of my life.

Cy walked me into his shows, the best seat in the house. One, “I Love My Wife,” a satire of the sexual revolution of the 1970s he created with Michael Stewart, was a would-be ménage à quatre. Cy put the band up on the stage like a Greek chorus. It was revolutionary.

“On the Twentieth Century” was a big choo-choo train of a show in which a rubbery Kevin Kline cavorted, an instant star, and Madeline Kahn was divine. And then there was “Barnum,” with real circus performers and the glorious song “The Colors of My Life.”

The last time I saw Cy was at a party in New York in the early 2000s. We met around the shrimp. He looked spiffy. We caught up with the same ease as ever.

“I’m happy. Love my kid. Shelby is somewhere.” He gestured toward a crowd.

I told him I loved “The Life,” which was his latest on Broadway. “Ready for six degrees of separation?” He nodded, all ears. “Ira” — Gasman, librettist and book writer of that two-Tony-winning musical — “is also a friend. So funny, such style. That cigar. Quel coincidence.”

“Thanks. Ira’s a little meshuganah, but a lot talented.” We inhaled more cheese. “What are you doing?” he asked.

“Working on another self-help book, ‘Over It: Getting Over Being Under It.’ ”

He laughed. “Great!” The Cy seal of approval. It was our last conversation. Two years later he died, a heart attack.

I listen to his music every day with love on Legends, 100.3 FM, the Great American Songbook station out of Palm Beach. I smile as I sing along, “Out of the tree of life I picked me a plum. . . .”

Susan Israelson, the author of “Water Baby,” a novel, and co-author of “Lovesick: The Marilyn Syndrome,” is at work on “Magic Moments,” creative nonfiction with essays, poetry, and illustrations. She lives in East Hampton.