“Let’s talk about movies.”

Anyone who spent time with Esteban Cordero during the last years of his life became used to these words, which he repeated whenever conversation would drift to the medical topics that envelop so many of the 80-and-over set. He was resolutely, even defiantly, uninterested in talking about aches, pains, X-rays, M.R.I.s, CAT scans, cancer treatments, sickness. He hated talking about doctors and even to doctors. But he loved talking about movies.

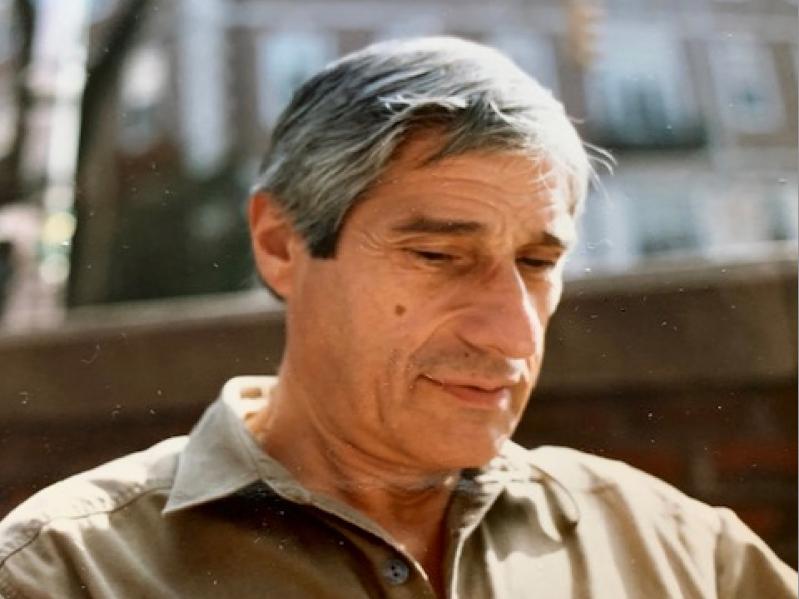

Mr. Cordero died on Sept. 15 in New York City. He was 92.

He was born in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, to Sixto Remigio Cordero and the former Carmen Queipo on June 9, 1931. It was a few years later, when his family moved to the Argentine capital, that he received his education in the literature, art, and film that would entertain him all his life. Those were the movies he liked to talk about — “Battleship Potemkin,” “Grand Illusion,” “Port of Shadows,” “Brief Encounter,” “Rashomon.”

Sergei Eisenstein, Marcel Carné, and Akira Kurosawa were his earliest heroes, later followed by Americans like David Lynch and Quentin Tarantino. Their works sat on his bookshelves in New York City and East Hampton, which held an eclectic collection of VHS tapes, DVDs, and books on World War II history, the Spanish Civil War, Mexican art, Soviet art and propaganda, and titles by Anton Chekhov, Roberto Arlt, and Jorge Luis Borges.

The tag sales and Ladies Village Improvement Society thrift store he adored visiting produced other, more idiosyncratic finds, from “The Intimate Lives of Famous People” and “The Gay Book of Days” to gardening and local history books.

From Argentina he moved to Mexico in the 1950s, where he was an advertising copywriter and occasional model for McCann Erickson. It was there he met Wilma Milson, a Brooklyn girl on a summer holiday. His first words to her — “May I park here?” — were taken from a phrase book. The answer was yes. They were married six months later on Feb. 17, 1961.

In the 1960s they moved to New York City, where he wrote ads for Eastern Airlines. For 10 years the couple would regularly travel to Europe, India, Nepal, and other destinations on free last-minute tickets before settling down and welcoming two daughters, Alexandra and Kristina. He later opened his own agency, En Espanol, with a couple of partners.

In 1980 the family came to East Hampton, first to a small house in Springs, and then Northwest Woods.

Mr. Cordero was not much for organized religion. He was raised Catholic and his wife was raised Jewish. Their devotions were of another order — cooking (from pizzas and asados to coq au vin and choucroute Alsacienne), the beach (always Indian Wells, far to the right of the lifeguard stand), and his basement workshop, where he would frame prints, build tables, and fix and fiddle.

He was especially enthused at the influx of Latin Americans to East Hampton. Whenever a fellow Spanish speaker would come by to do garden work or house painting, he would serve them lunch and they would exchange tales of how life had brought them to the town he loved so much.

Toward the end, as his cancer progressed and he retreated into a bit of a private world, he would sit outdoors in the late afternoon, drink in hand, admiring his wife’s flower garden, with statues of Buddha and St. Francis and outdoor sculptures by friends. To anyone who would listen he would say, “Thank God for East Hampton.” Then he would drain his glass of wine and retire to the bedroom, where he would watch a movie on Turner Classic Movies.

To honor him, his family suggests that friends and family do the same — watch a good movie.

Mr. Cordero is survived by his wife and by his daughters, Kristina Cordero of New York City and Santiago, Chile, and Alexandra Cordero of New York City, and by his grandchildren Beatrice and Carlota Gumucio, and Lucas and Pablo Cordero-Dinnerman. — Kristina Cordero