My grandparents had a passion for steamships that, as these family inclinations do, has somehow trickled down to me as a vague sentimental affinity, even though the age of the great trans-Atlantic crossings is long gone: “We like ocean liners.”

My grandfather, Arnold Rattray, was the editor of The Star but also a ticket agent for the Cunard Line. He sold passage on the Cunard and White Star liners out of the newspaper front office between the late 1920s and the early 1950s. The ships’ names ring in our modern ears with perfumed mystery and grandeur: Berengaria, Scythia, Mauretania. . . . I think Arnold picked up his agent’s license in 1928, the year the Cunard Line and the White Star Line — and the Holland-America Line, the French Line, the North German Lloyd, and even officials from the Navigazione Generale Italia, swinging walking sticks and wearing suits tailored to show off their waists — came sniffing around Fort Pond Bay in Montauk.

The steamer companies conferred and held magisterial inspections but eventually decided Montauk wouldn’t be suitable as a terminal for ocean liners. I imagine this must have been a sharp disappointment for Arnold, particularly when the stock market crashed the next year, in 1929, and the Depression followed, and the Rattray family found itself scraping by, eating many repetitive dinners of cheap potatoes and bluefish (which were caught in Gardiner’s Bay by father-in-law, and free).

My grandfather’s own parents — my paternal great-grandparents, the Rattrays, were poor but educated Scots with a salty sense of humor and heavy Glaswegian accents. Faether taught mechanical engineering at Berkeley, but the family house in Alameda, outside of San Francisco, was crowded and noisy, everyone playing an instrument and singing choral music in the tonic-sol-fa. What did they think when Arnold, the baby of six siblings, dropped out of high school at the age of 15 to work for a shipping magnate on the docks at Oakland? All Arnold wanted to do was steam around and around the world. I can relate.

At 19, Arnold got his wish and boarded his first Cunard liner: It would take him to France as a sergeant in the medical corps.

On a Thursday in June 1918, he left barracks at Camp Merritt, New Jersey, and marched in the predawn darkness to the landing at Spuyten Duyvil Creek to board a ferry that carried them down the Hudson River to Pier 54, the Cunard pier, on the west side of lower Manhattan. The Lusitania had left from this pier, before it was torpedoed by a German U-20 in ’15. The Carmania brought survivors of the Titanic to Pier 54 in ’12. It wasn’t just any Thursday in June. It was June the 6th, 1918: the day the American Marines hurled themselves across a wheat field at the German machine-gun nests in Belleau Wood. The day, they say, the “American Century began.” The first great American bloodletting on foreign soil, the first test, the first national intervention, the birth of the legend of the U.S. Marines.

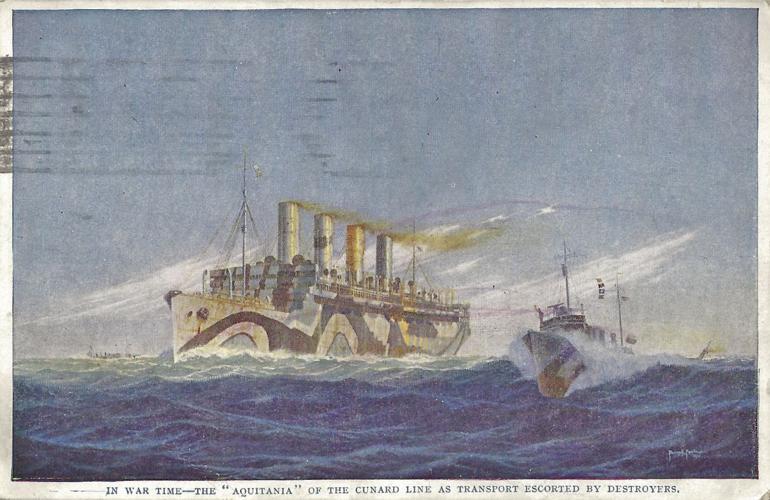

Some of the troop transports in World War I were aged freighters, foul-smelling rust-buckets, but some were the finest passenger ships the world has ever seen, and Arnold was assigned to the Aquitania, the most glamorous, most modern, most lovely liner ever built. The Aquitania, once shiny black on its sides, had been freshly painted with zebra-zigzagged “dazzle” camouflage, which, at the bow, curled into a sinister Halloween grin.

Cunard. The Aquitania! As a noncommissioned officer sailing on an extraordinary ship, Arnold escaped the lower holds where canvas berths stacked four or five high were strapped to iron pipes called standees. He was assigned to a small stateroom that he shared with several other sergeants; one man, who slept on a cot between the bunks, had to be woken so he could lift it up when someone else climbed down to go to the latrine. Bunks lined the promenade deck and hallways. Mahogany trim had been stripped from the dining saloons, and extra berths of rough pine nailed incongruously to the fancy work of the staterooms.

No one got to see the Statue of Liberty as the Aquitania left the Port of New York: They were all confined to their berths, in case spies were watching. The Aquitania steamed through the Narrows, then south of the Borough of Queens into the Atlantic. A man-of-war joined the convoy at Sandy Hook. At midday, the men were allowed on deck to watch America fade into the distance. The ship was joined by a convoy of half a dozen more British and American transports out of Hampton Roads. A dirigible from an Army base at the Rockaways, plump and comical in its slow maneuvers, seemed to be following them, and a pair of hydroplane patrols above. The weather was unsettled. By midafternoon they could no longer see land, and a few men were already throwing up.

The light craft — airplanes, torpedo boats — accompanied them out to the hundred-fathom curve and then returned to port.

Not far from Iceland, it turned cold. The sun stayed up until 9:30 at night. At the 15th meridian west, the Aquitania was met by an escort of four European destroyers, who ushered her through the danger zone. Then they headed east, toward Ireland, and the seas were high. The man-of-war raised a Union Jack signaling their entrance into British waters. The boys were ordered to wear life belts and carry canteens of water at all times. They were ordered to sleep in uniform, ready to jump if the ship was torpedoed.

The Aquitania fired depth bombs, and Arnold watched the sub chasers as they scoured the water, relentlessly running fore and aft, as they cruised south of Ireland, through St. George’s Channel, into the Irish Sea. The boys could soon see white beaches and lighthouses. The green water of the Irish Sea, the Isle of Man off the port side, and then Liverpool. It was a slow slip up the Mersey, past elevated light railways carrying shipping crates, an awe-inspiring flotilla of tugs, cruisers, scows, punts, steamships, yachts, and transports.

A band at the wharf played “God Save the King” and “The Marseillaise” and “It’s a Grand Old Flag.” There was a long wait on the landing stage, and the men flopped down on their packs. They couldn’t help but notice that there weren’t any young or even middle-aged men anywhere to be seen, just women and children, the lame and the halt.

My grandmother Jeannette loved steamships, too.

Jeannette and Arnold met in the Far East, in Indonesia, in fact, in 1925. He never returned to San Francisco after the war, but stayed in Paris, living with a bob-haired waif in a bohemian quarter, in an apartment building where Man Ray kept a studio, then lived in Moscow for a time, and then Japan. My grandmother’s ocean liners? That is a whole other steamship story. She set out from East Hampton as a “girl reporter” in 1923, headed for Constantinople and then China, where she would interview warlords and type up her interviews — going on and on at great length; I relate — on a portable typewriter she carried with her in her steamer trunk to Shanghai.

All that’s left of this 20th-century grandeur is a thick, very heavy, black-wool deck blanket embroidered with the words “Queen Mary,” clearly pilfered, that is upstairs right now, smelling of mothballs (antique mothballs, themselves left over from the previous century) on a shelf in a linen closet, and a black Bakelite ashtray, also from the Queen Mary, that made its way home — naughty grandma — but, since no one smokes anymore, either, and we are all boring, has fallen from use.