My son entered a screenplay into a national contest. Took grand prize. Won $3,000. Life was good. Movies made sense.

Six months later, he was still waiting on his winnings. Silence and no replies. Life was unfair. The movie had a wrong ending.

That’s when I called Mike Gordon.

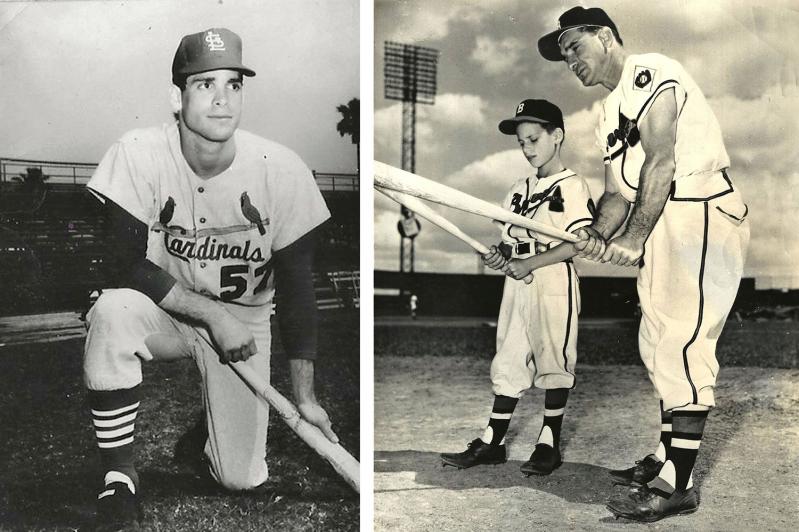

Mike Gordon was a dear friend I had met on the softball field in Bridgehampton. He swung easily and the ball traveled mightily. A classic pull hitter, he was so far in front of every pitch that the opposition played him in foul territory, in deep left field, where Carl Yastrzemski spent his high school afternoons. Everyone loved Mike Gordon. The melding of machismo and kindness in one man was irresistible; he pulled up every Sunday morning with a big Harley and a bigger smile. And then he volunteered to catch every game, the position he had played in the St. Louis Cardinals farm system after serving in the Army.

In the first game of a spring training doubleheader with the Cards, a foul ball hit his throwing hand and broke his index finger. He said Bob Gibson’s fastballs hurt his glove hand even more, so he played on. Between games, he saw his name penciled in to catch the nightcap as well. (Tim McCarver needed a day off.) “Skip,” Mike told his manager, “that foul ball broke my finger.” The manager stared at him and asked, “Are you a catcher or a pansy?”

In the second game, five Phillies stole second base and Mike Gordon’s future. He was sent to the minors with his busted finger and broken dream. He was devastated. Baseball was the family business — his father, Sid Gordon, had starred for the New York Giants and Boston Braves. Twice an All-Star, he hit 30 home runs when that was a feat. In 13 years in the majors, he had twice as many walks as strikeouts and a busload of buddies. The Gordons were close friends with the Robinsons, Rachel and Jackie.

In the second game, five Phillies stole second base and Mike Gordon’s future. He was sent to the minors with his busted finger and broken dream. He was devastated. Baseball was the family business — his father, Sid Gordon, had starred for the New York Giants and Boston Braves. Twice an All-Star, he hit 30 home runs when that was a feat. In 13 years in the majors, he had twice as many walks as strikeouts and a busload of buddies. The Gordons were close friends with the Robinsons, Rachel and Jackie.

Mike Gordon worked in law enforcement for the City of New York, and then became a private detective. Soldier, catcher, copper, sleuth. Years later, Mike had a heart attack. A stranger shoved aspirins down his throat and helped save him. Quadruple bypass helped too.

When my son didn’t receive his winnings for his screenplay, I called Mike Gordon and told him the story.

It took him one week to find the outfit responsible and another week to collect the money. When they met, my kid was less impressed with his investigative skills than with the man himself. Mike was Hollywood handsome, genuinely humble, good-natured, and generous. His fee? Satisfaction. He just wanted to right a wrong. He had kids too. And a more devoted father you’ll never find.

My son’s next script featured a handsome private eye who was nostalgic for his Little League days. He couldn’t make the lead character a charismatic soldier/catcher/copper/gumshoe with a Harley because no one would believe it. He made him a drunk instead. Everyone could buy that.

Mike Gordon had another heart attack this summer. Aspirins did him no good. He died on Aug. 13, on his father’s birthday. Mike was buried in Sag Harbor two days later. The funeral was awash in tears and love. No one could believe he was gone. Not his wife, not his three kids, his grandchildren, his brother, his friends, or his softball gang. Every speaker said Mike Gordon was his or her best friend, and the person to call in time of need.

This time, there’s no Mike Gordon to call. Some movies end all wrong.

Bruce Buschel is a writer who lives in Bridgehampton.