In East Hampton, the lifespan of the so-called Spanish influenza was for the most part during the winter of 1918-1919 and into early spring. Leafing through old issues of The Star from that time, the flu’s effects here could be told from the number of dead and ill.

In those days, the notes from the various villages and hamlets frequently listed who was visiting, the names of summer tenants, and who was sick. The first report of someone ill with the flu was in September 1918 from Amagansett. A fortnight later, there were 6 cases in East Hampton and 35 cases by Oct. 11. A week later, the paper reported “some 125 cases of colds, grippe, and influenza.”

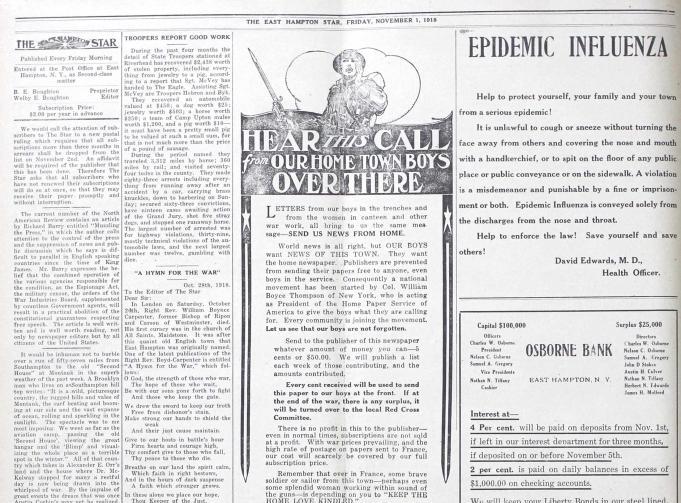

Schools were closed and children ordered off the streets. A quarantine was imposed at all the Long Island Coast Guard stations. Sneezing or coughing without properly covering the face became a misdemeanor. Yet influenza continued to spread.

The head of the New York Board of Health became convinced about healthy carriers of flu after reading an account of an outbreak immediately following a ship arriving in Alaska whose passengers had all been carefully examined before their departure from San Francisco and found to be symptom-free.

On Jan. 3, 1919, Virginia Seely, aged 7 months, died in Southampton. Her father died two weeks later, also of influenza.

Arthur Dominy, a member of the East Hampton family of celebrated craftsmen, died at home in Bay Shore.

The E.J. Edwards Pharmacy, in the Main Street building that is now the Star office, was advertising something called Kresano as “splendid aid in the prevention of infection.”

Reports of new cases declined in April and May. Summer came, and from The Star, it appeared that the influenza threat had subsided. On the Monday morning after the July 4 weekend in 1919, the Long Island Rail Road sold a record 226 parlor car seats on its two westbound trains.