Some parents might have walked away after their child committed murder, too horrified to cope. Shelley Gilbert did the opposite. After her son, Thomas Gilbert Jr., shot and killed his 70-year-old father on Jan. 4, 2015, she paid for his defense attorneys, expert witnesses, and psychiatric examinations. She spent so much money that she never totaled it up; actually, she was afraid to know.

As a teenager, Tommy had exhibited signs of obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression; it may later have developed into full-blown schizophrenia. He managed to graduate from Princeton six years after entering, played a good game of tennis, and had an active nightlife, but was never able to keep a real job. One psychiatrist told his parents that unmedicated schizophrenics can play sports and socialize, but cannot settle down to work. He took a bartending class, which came to nothing, and got catering jobs here and there but frequently left before the event was over.

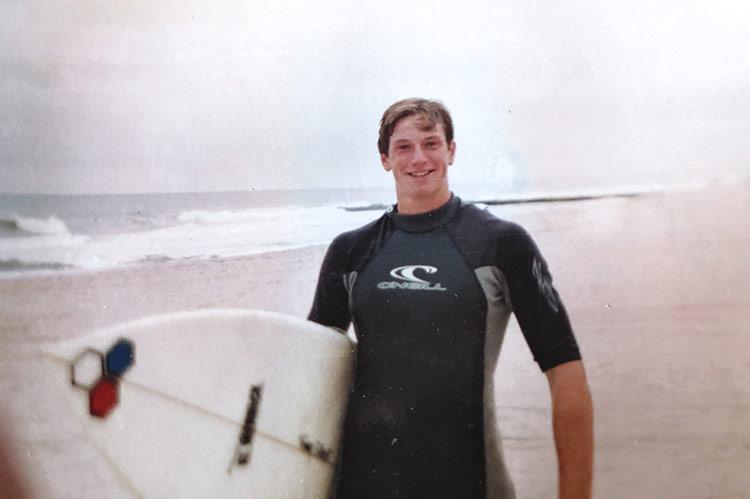

The Gilberts, who had a vacation house in the Georgica Association, paid for their son’s apartment in New York, his bills, his membership in the Maidstone Club, and gave him an allowance. Mr. Gilbert was “spoiled,” said the prosecution during his trial, but his mother said it was all therapeutic. “You want him to see as many friends as possible. Tennis and surfing, it helped relieve stress. It was almost like medicine. It was the best we could do for him.”

“Our goal was to keep him close,” she said. “If you did anything that really bothered him, he would disappear. He was disappearing anyway. You wouldn’t hear from him for long periods of time. So, we were doing everything we could to keep him in our orbit.”

She sat through most of the trial, leaving the courtroom only when the prosecutor was describing the details of the murder. “He’s my son. I love him dearly,” she said recently during a four-hour interview at a Manhattan restaurant. “What he did was not him, it was his disease . . . what a wonderful soul he was — that’s Tommy Gilbert.” What took place that day in the family apartment on Beekman Place, she said, was “as if Roger Federer got a tumor on his hip and you would say he’s a rotten tennis player.”

On the morning of the day he died, Thomas Gilbert Sr. left a message for his 30-year-old son saying he was again cutting his allowance. The younger Mr. Gilbert had been getting $1,000 a month; now it would be $300. The prosecution seized on that as the motive for murder, giving short shrift to the numerous mental competence hearings — on and off for more than three years — that preceded the trial.

Her son had been acting oddly, Ms. Gilbert said — hallucinating, claiming that the apartment was “contaminated” — even before he entered college. At least two psychiatrists found him to be mentally ill and not competent to be tried on murder charges. The Manhattan district attorney’s office disagreed, however, and hired forensic psychologists to examine him.

One of them, Stuart Kirschner, testified, according to court transcripts, that “although there are indications in the record that Mr. Gilbert has a psychiatric history, I saw absolutely no symptom of a mental disorder that would impact on his ability to proceed to trial.” The defendant, he told the court, understood the charges against him, as well as the roles of the prosecutor, defense attorney, judge, and jury, and was concerned about the media coverage his case had received.

That is the legal standard for competence to stand trial, established by the Supreme Court in 1960. Many legal experts feel it is outdated. Ms. Gilbert believes that her son was never competent to stand trial and that it was unconstitutional. He had refused to talk to either his lawyers or the psychiatrists hired to assess him, she emphasized, and was never aided in his own defense. He was prone to frequent nonsensical outbursts during the trial and often refused to appear in the courtroom at all.

In fact, there were storm warnings of mental illness in Tommy Gilbert’s ancestral DNA, going back to his father’s mother, who, according to court records, was considered “psychotic.” On his mother’s side, it was worse: Her father was diagnosed as bipolar and took his own life at 57, jumping from a fifth-floor hospital window.

“I have lived with mental illness twice now. I understand it exceedingly well,” Ms. Gilbert said.

Alex Spiro, her son’s first defense attorney, brought up the family history when he cross-examined Mr. Kirschner, who had suggested that Mr. Gilbert was faking mental illness, during a pretrial competence hearing. It sounded like there was a mood disorder in the family, he said. Was that not significant? the lawyer wondered. “You are aware that they checked on Mr. Gilbert’s grandfather, that he said he was perfectly fine and he then jumped out of a window to his death?”

“It’s not uncommon for people who commit suicide to say they’re okay because if they’re bent on committing suicide they don’t want to tell people what the plan is,” Mr. Kirschner replied.

“Right, and they might also be faking wellness?” Mr. Spiro fired back. Mr. Kirschner answered that it was more common to malinger during a competence hearing than to fake wellness.

Justice Melissa Jackson, who presided over the trial, agreed with the prosecution, ruling Thomas Gilbert Jr. mentally competent to proceed with the trial.

An insanity defense mounted by his second attorney, Arnold Levine, proved futile. The jury was not swayed by the argument that he did not know that what he was doing was wrong: He had bought a gun and gotten his mother out of the apartment before shooting his father in the head.

Even after the conviction that followed the five-week trial, Shelley Gilbert held onto hope that her son would receive a minimum sentence, and that, in prison, he would get the help he needed to one day re-enter society. “I don’t know what the judge was thinking when she gave him the max” — 30 years — she said. “What good is that going to do?” Would it, she wondered, deter “the next schizophrenic person who is in a rage and is about to kill somebody? Would that person say, ‘Oh, no. Tommy Gilbert got the max’? That’s not going to happen.”

She had hoped the Department of Corrections would place her son in a prison closer to New York City. That did not happen. He is in the Clinton Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in Dannemora, N.Y., near the Canadian border. She has not visited him yet. It’s a long trip, and there’s a chance, she said, that he might refuse to see her if she did get there. Meanwhile, privacy laws prevent her from knowing if he is getting any type of meaningful mental health care behind bars.

She did see her son a few times (he didn’t always agree to her visits) during the years he was at Rikers Island awaiting trial. She never asked him to talk about what happened. She knew it would be useless, she said. Only once did she even mention his father — she told him about the memorial service they had held for him. He thought it sounded “nice.”

Ms. Gilbert credits a strong support system with getting her through the last five years. “When Tom died, even before the police came, I thought, all my friends and family will flee — because they would be so horrified.” She could not have been more wrong. Friends she has had since grade school have stood by her; people she knew only in passing have become staunch supporters. Her daughter, Mr. Gilbert’s younger sister, was the only subject she would not discuss. “She needs to get on with her life,” Ms. Gilbert said.

She is certain that she and her husband did everything they could to get help for their troubled son. “We’re not irresponsible people.” Yes, she said, they could have stopped his allowance until he agreed to sign himself into a psychiatric facility voluntarily, but they feared he would wind up homeless and disappear from their lives completely.

Mr. Spiro, the lawyer, said that made sense to him. “The system was broken more than the Gilbert plan was broken,” he said. “There are some people who would say, ‘Let him sit in jail for another night.’ You could tell some kid to sit in jail another night and you could go to his cell the next morning and he could have taken his own life.”

The case was not about privilege or a spoiled child shooting his father in cold blood, Mr. Spiro said. “I think this case is really about trying to find a way so that our mentally ill don’t fill every jail and prison. . . . We have a draconian sense of justice that doesn’t deal with them in an appropriate way.”

—

This is the final installment of a three-part series. Thomas Gilbert Jr. is serving a 30-year term for murdering his father.