"The Father of Baseball," Henry Chadwick, whose retirement house in Noyac, not far west of Trout Pond, still stands, is to be among those inducted into the Suffolk Sports Hall of Fame on Oct. 1.

Originally, this year's class, which includes Mark Herrmann, a retired Newsday sportswriter who began his career at The Southampton Press in the early 1980s, was to have been inducted on May 26, at Watermill Caterers in Smithtown, but the coronavirus pandemic intervened.

Born in England in 1824, Chadwick came as a teenager with his family to Brooklyn, and apparently saw his first baseball game in 1856 on Hoboken's Elysian Fields while writing about a cricket game there for The New York Times. Smitten, he said that in baseball — derived, he maintained, from rounders and cricket — "all is lightning; every action is as swift as a seabird's flight."

In short order, Chadwick, who worked as a sports journalist until his death, in 1908, at the age of 84, helped to shape America's pastime, journalistically, statistically, executively, serving on and chairing early rules committees, and morally, railing in the periodicals he wrote for against alcoholism and gambling — as his grandfather, a Methodist minister, had done.

That such things as steroid use and sign-stealing still trigger opprobrium these days can be traced to Chadwick's philosophy enunciated a century and a half ago, Andrew Schiff, his biographer, said during a telephone conversation Sunday.

"Even then, long before endorphins, Chadwick knew that sports offered a way to improve one's body and mind," an ethos in step with the American spirit.

Chadwick and baseball were well met, given the fact, said Schiff, that the mid-1800s was a period in which America was asserting itself in the arts, in literature — Emerson and Whitman come immediately to mind — and in sport as well.

Despite what it says on Chadwick's Hall of Fame plaque in Cooperstown, "he did not invent the box score," said Schiff, "though his influence on the game was multifaceted. He was a journalist, statistician, a rules committee member, and a moral voice for the game. . . . While he didn't invent the box score, he did invent the in-game scoring system. Though the modern scoring system looks much different from what Chadwick created, the use of the term 'K' for a strikeout still remains part of the terminology that came from his original invention."

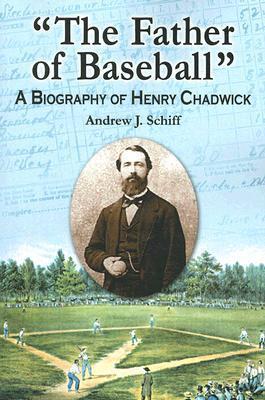

"Chadwick, as I've said in my book" — "The Father of Baseball: A Biography of Henry Chadwick" — "was clearly a giant in his time. And since baseball is the sport of America, the game most identified with American culture, Henry Chadwick was one of the men who helped America discover its identity."

In addition, said Schiff, "He was also the inventor of sports journalism in America. In the days before radio and television, his writings were a descriptive link between the playing action and the fans. . . . Before Chadwick's contributions, newspapers only sporadically mentioned games, with an occasional nod to cricket and horse racing. However, within a decade after the appearance of his first articles in the late 1850s, dailies routinely covered sporting events, and by the 1880s sports pages had been developed."

Sag Harbor claims Chadwick because he lived in Noyac for about two decades in the late 1800s, Benito Vila, a Sag Harborite himself, wrote in The Sag Harbor Express on the occasion of that village's 300th anniversary in 2007.

Vila has a scorecard of Chadwick's that dates to an 1874 game played here between teams from East Hampton and Bridgehampton.

As part of the 300th anniverary's celebration, two baseball games under rules extant in 1864 were played at Mashashimuet Park, one that year and one the next, matching the Sag Harbor Nines and the New York Mutuals Base Ball Club of Bethpage.

The players, who in 2008's game included Vila, Sean Crowley, Fred Marienfeld, Matt Malone, Gregg Schiavoni, Paul Federico, and George Kneeland, were bare-handed, the pitchers pitched underhanded from a line — a string of popcorn actually — 45 feet from a saucer-shape plate, with the catcher well back of it and the umpire to the side.

The strike zone was from the shoetops to the shoulders, there were four balls and four strikes, called at the umpire's discretion, all base runners advanced on a walk, you were out if the ball you hit was fielded on one bounce, or bound, either in fair or foul territory, and downward-chopped balls spinning into foul territory after having hit fair were . . . fair, reminiscent of cricket, the tortuous game against which the Americans rebelled.