Ever since having to abandon somewhat beyond the midpoint an open-water swim from Montauk Point to Block Island in September 2017 that would have been a first, Spencer Schneider has thought of giving what Sinead FitzGibbon has called “the local Everest of swimming” another try.

It all came together recently as the 64-year-old Schneider, Drew Harvey, 27, Michal Petrzela, 49, and the 54-year-old Jeremy Grosvenor made the crossing under the Dawgpatch Bandits’ banner as a relay, in 8 hours and 44 minutes, thus laying claim to being the first to achieve the feat in an easterly direction. Lori King of Amagansett swam it in the other direction, from Block Island to Montauk, in the summer of 2022.

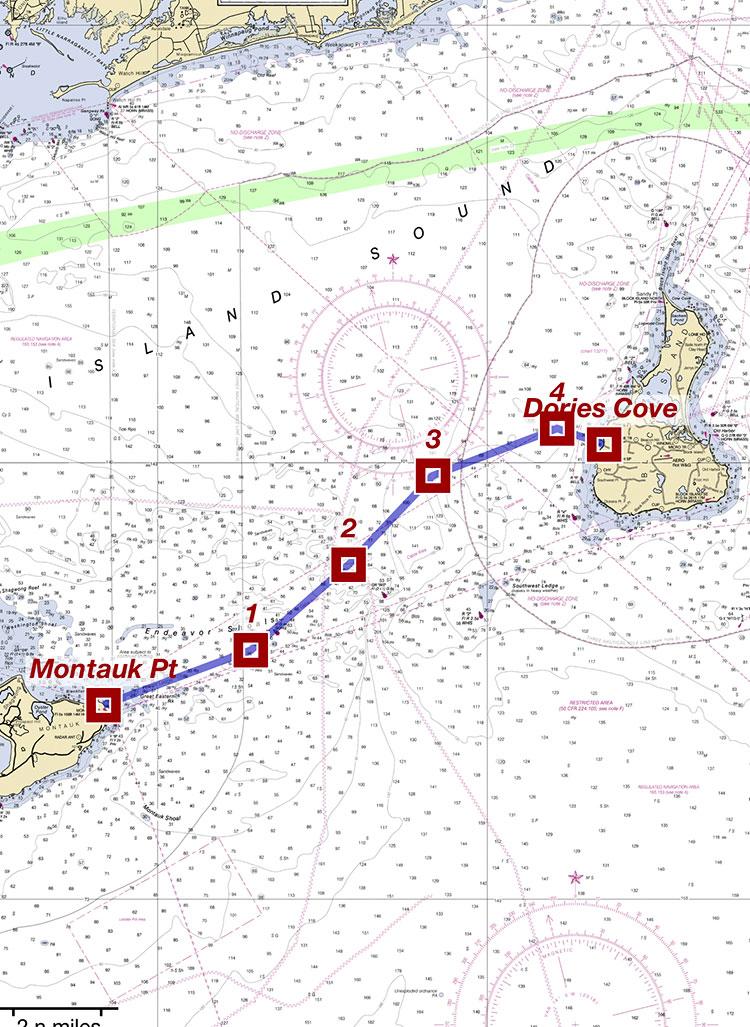

“Lori’s route was much different,” Harvey said. “It’s 14 miles to Block Island as the crow flies, and we tried to cross the current as close to the mark as possible. We ended up swimming 15.8 miles.”

Asked to sketch the route, he drew on a manila envelope an elongated, recumbent S linking Montauk Point and Dories Cove on the west side of Block Island.

When such a demanding test is considered, several potential problems present themselves, having to do with tides, currents, water temperature, winds, weather, and “sea life.”

Concerning the latter, Harvey said that “fishermen are always telling you not to try it because of the sharks. We didn’t see any, though we did see a pod of about 30 dolphins at around the halfway point. I was in the water then. Ultimately, they were friendly, but they did come very close. The key is to keep swimming, not to stress out. They can sense what you’re doing in the water.”

“There are only two windows of time in the year when you can attempt this swim,” he added, “the chief considerations being the tides and currents. You’ll never be able to swim against the tides.”

“You have to get off the Point at the right time, at slack tide, which in our case was at 6:31 a.m. You’re actually heading toward the southern point of Block Island at that point. You have to go hard at the start, and Spencer — he was our first swimmer — did. You have to get out a certain distance before the tide changes; otherwise, the current coming into Block Island Sound will push you north toward the North Fork. Two hours into it you want to be a third of the way done. . . . If you miss your marks your chances of success fall exponentially.”

If the tides were timed correctly, said Harvey, the outgoing one at Block Island, some six hours later, would “push you back south so that you finish where you need to be. . . . Once the outgoing current picks you up, you drop down south quickly. Block Island is a much smaller target than Long Island is — you might miss it and be swept into the ocean if you’re pointed too far south. . . .”

“Spencer led off — he got us going great. We rotated every half-hour, observing all the Marathon Swimmers Federation’s rules. At 7:01, I started swimming and then Spencer got out. Tom Heine and my dad [Dave Harvey] were on the 32-foot guide boat, captaining and spotting the swimmers. Nick Stevens, who’s also from Sag Harbor, and is a lifeguard at the Georgica Association, paddled the entire way, keeping the swimmers on the line and keeping them between him and the boat as a safety precaution.”

“After me, Michal swam. We’re all open-water swimmers, which is key. This is probably the most exposed swim you can do on the East End of Long Island. . . . Block Island is like the white whale of open-water swimming on eastern Long Island. The logistics and the sea life are genuine concerns. Fishermen, as I said, will say, ‘Don’t do that.’ The statistics are on your side, though we tried to be as smooth as possible, just swimming, not making a fuss. A lot of it is chance. There could have been sharks, there could have been whales. It’s a risk you assume when you do something like this.”

As for the water temperature, “it’s always a factor because of the ocean currents and the depth of the water, which is consistently over 100 feet. The day we did it the water temperature was in the high 60s . . . 67 to 69. The beauty of doing it as a relay, of course, is that you’re able to warm up when you get out of the water.”

Harvey said he met Petrzela, a frequent winner of the Montauk Playhouse’s long-distance ocean swims, when they set out on Heine’s boat from the Sag Harbor Yacht Club at 5 a.m.

“Spencer recruited him. Jeremy” — with whom Harvey and Schneider have swum long distances before — “didn’t commit until he was on the boat that morning. We were prepared to do it with three, but it was key that he decided to do it. It would have been a much different day if he hadn’t; otherwise, we wouldn’t have been able to keep up the pace we needed to make it across. . . . We all finished the last 500 yards together.”

The singular relay was not done as a fund-raiser, Harvey said, but as a sporting adventure attesting to the value of fitness and to natural, versus drug-induced, highs.

Harvey founded the Dawgpatch Bandits, a nonprofit promoting mental health and fitness, following the death eight years ago of Mike Semkus, a Sag Harbor teacher, coach, lifeguard, and triathlete who became addicted to the opioids that had originally been prescribed to treat a soccer injury.

“We’re trying to get guys like Mike Semkus, guys who need endorphin outlets, into adventure-style sports — we want them to push themselves in the natural environment, whether it be through swimming, running, or biking challenges, so their mental health will improve.”

To that end, the Bandits have, he said, constructed a dozen all-purpose fitness areas, six of them on Long Island, with four out east — at Pierson (Sag Harbor) High School, at the Phoenix House in Wainscott, at Shelter Island’s Fiske Field, and at Stony Brook Eastern Long Island Hospital in Greenport. “They’re for everybody,” said Harvey, who has twice crossed the United States on a bicycle, “but particularly for those in recovery. We want to make sure the local community is taken care of.”

Asked what the Bandits, who have now done about all the long-distance swims that can be done out here, would do next, the interviewee replied, “We might do some longer prone paddles, from Block Island into uncharted waters.”

Those interested in taking part in Bandit adventures can keep posted through dawgpatchbandits.com and through @dawgpatchbandits on Instagram.