It was tide, not bombs, that did in Fort Tyler.

Fort Tyler, a pile of rubble and concrete walls that had been a landmark for boaters and favorite fishing spot, has nearly been consumed by the sea after standing for 120 years on a shrinking island north of Gardiner’s Island.

The Ruins, as the crumbling fort is known, had long been part of local lore. On-and-off bombing practice by the United States military had made it off-limits to civilians for fear of unexploded ordnance. Ed Michels, East Hampton Town’s chief harbormaster, said that a bomb found there not long ago was safely blown up by a demolition team. The blast was felt all the way across Block Island Sound in Montauk.

At high tide now, the sand island on which the old fort sits is gone. An aerial photograph taken during an especially high tide in the fall shows only the tallest few remnants of the walls above water.

In was in 1898, at the start of the Spanish-American War, that attention turned to long-neglected defensive positions along the East Coast. Without firepower at the entrance to Long Island Sound, enemy ships might approach New York City from the back, wreaking havoc before the U.S. Navy could respond. The Eastern Shield, a string of fortifications from the Connecticut shore to Montauk, was rushed into construction.

Work on Fort Tyler was commissioned by the War Department. It was to be built on a 14-acre island on what had until the blizzard of 1888 been known as Gardiner’s Point. The fort was not completed by war’s end. Troops were never stationed there, and no guns ever mounted. For years, its only occupants were seabirds and the occasional group of picnickers — including at least one class from East Hampton High School.

Building Fort Tyler had been a significant undertaking. A total of $500,000 had been set by the War Department at the outset. Tap rock was brought by barge from the Palisades for the base of the 30-foot-tall concrete walls. Workers slept aboard ships anchored nearby.

Had Fort Tyler ever been occupied, headquarters for its detachment would have been on Fishers Island, at a larger fort that was named for Major Gen. Horatio G. Wright, a distinguished Civil War commander and head of the Army Corps of Engineers from 1879 to 1884.

No one wanted the island, The Suffolk County News reported in 1924. “Congress some time ago passed a bill authorizing its sale but the spot seems to have no value to local people,” it said, noting that it had become “a picnic ground for sailing parties and a haunt for water fowl and bootleggers.” Visitors from about that time reported finding empty liquor bottles in abundance in one of the fort’s empty chambers, evidence, they said, of a rumrummers’ bacchanal. Then for a time, the island — by then eroded to about 3 acres from its original 14 — was under the authority of the Long Island State Parks Commission.

In July 1936 the Ninth Bombardment Group of the Army Air Force tested its new Glen Martin bombers there. According to the New York Herald Tribune, the air crews dropped metal containers filled with 100 pounds of sand and 2 pounds of black powder for a telltale smoke cloud up to 18,000 feet to simulate bombing runs, from 8:30 in the morning, Mondays through Fridays “until further notice.” Residents on the North and South Forks were not pleased. Then-New York Gov. Herbert H. Lehman got involved, adding to “the deluge descending on the War Department,” The Star reported that August.

Finally, acting Secretary of War Malin Craig announced that he had ordered the Army Air Corps to stop its bombing practice there after numerous complaints that the planes had frightened away fish and fishermen.

After World War II, the assaults on the fort became more intense, with live bombs, rockets, and machine guns trained on its crumbling walls.

Weekend reservists continued using the Fort Tyler ruins as a range, irritating fishermen no end. The Star reported that most of the firing took place in a half-mile radius of the fort from Marine Corps and Navy aircraft.

An account in The Star reported with restraint typical for the time, “For a time a helicopter equipped with a loudspeaker was employed to cajole the trollers from the danger zone. The conversations between the helicopter crew and the fishermen, conducted on the latters’ part in sign language, were often interesting to hear and observe. But as all good things must come to an end, Secretary of the Army Cyrus Vance announced that year that the area was no longer needed as a range.”

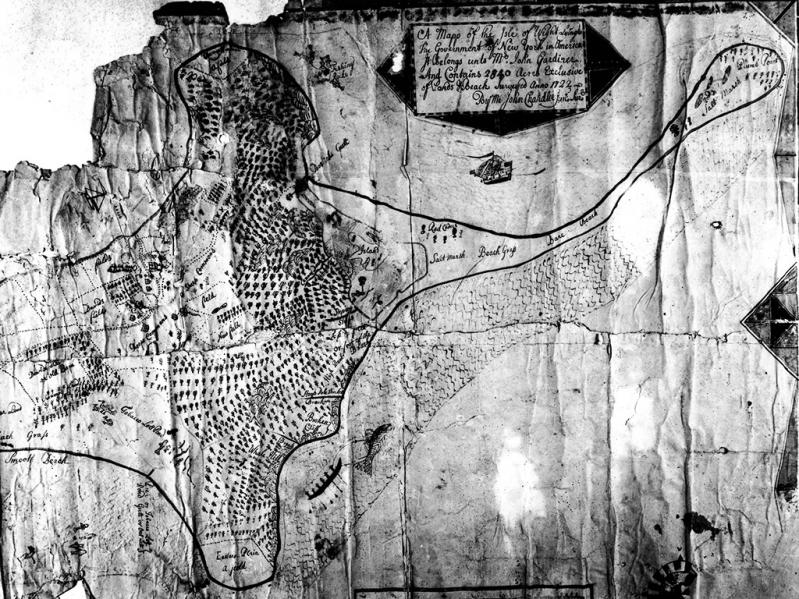

Just who owns the island or former island is not immediately obvious. The official tax map prepared annually by Suffolk County does not include that portion of the bay. In the 1700s and well into the 19th century, there was no question about it, as the site was connected to Gardiner’s Island by a long sand point running northward from Bostwick Harbor.

The federal government built a lighthouse there around 1854, and it was operated until it was removed to make way for the fort.

With the island nearly gone, Chief Michels said that the location might soon have to be marked with a buoy as hazard to navigation. “We know there is more ordnance out there. It’s going to be interesting,” he said.