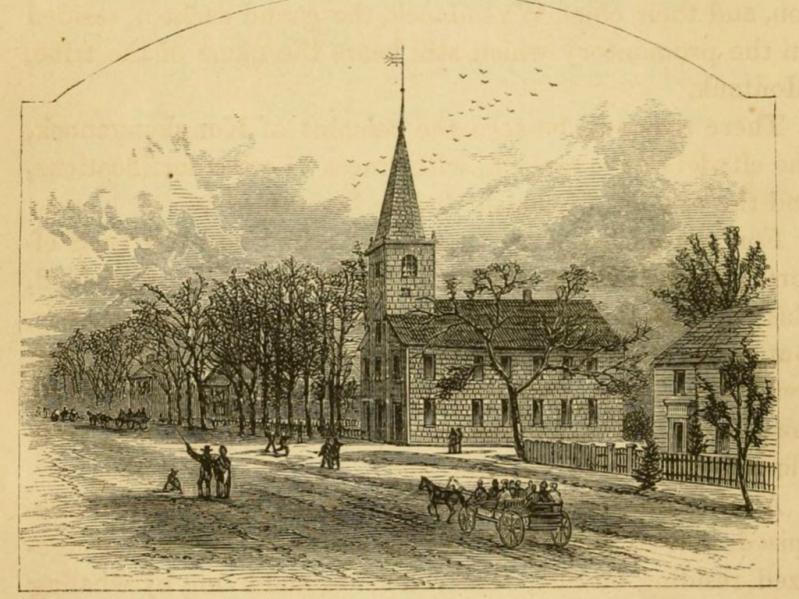

On the 17th of November 1723, an enslaved man named Peter crossed the massive granite doorstep of the East Hampton church. The pastor, Nathaniel Huntting, greeted him and asked if he was ready to make testament of his faith. He was ready.

“You believe that the Great God, who is ye father ye God & ye H.G. made you and all the world,” Huntting began, as he wrote on a scrap of paper later. Peter assented, and Huntting welcomed him as a member of the church, “This owning of God & engagement ye same as usual at ye baptism of other adult persons,” he noted.

In Plain Sight: |

And so, here is a fragment of a day long ago in which an enslaved man, “Peter, negro sevt. of Capt. Burnet,” speaks to the present, if only indirectly.

Voices of the enslaved in the North are few, though slavery existed here for 200 years. First-person slave narratives exist, but the vast majority are from the South. Yet accounts by people of African heritage whose paths crossed Long Island at one time or another provide glimpses of what their lives were like. They tell a story of brutality, deprivation, and, above all, resistance.

Peter was hardly the only enslaved person in East Hampton to join the church in the 18th century. There were his wife, Chriss, and their son Daniel and their other children. Sharfer, enslaved by Josiah Miller, was baptized in 1724.

The Rev. Samuel Buell, who followed Huntting in the pulpit, baptized Jude, Judge, Jars, Hittie, and Virgil during his much-acclaimed revival of 1764. Blacks attended worship in the town church, whether members or not; an area in the second gallery was set aside for them.

To get a fuller picture of American slavery it is necessary also to look back across the ocean to West Africa and to the stories the enslaved later told about their capture and the Middle Passage.

“They then came to us in the reeds, and the very first salute I had from them was a violent blow on the head with the fore part of a gun, and at the same time a grasp round the neck,” Venture Smith, who was first enslaved on Fishers Island and later visited and worked on Long Island, dictated in 1798.

Smith had been a child of about 6 when he was taken by native raiders in his home countryside, a flat and fertile region of present-day Ghana. It had been a time of tumult, and Smith — then still called by his birth name, Broteer Furro — and his family fled as an attacking force he estimated in the thousands swarmed over their village.

He watched as part of the attackers beat his father, demanding he tell them where his valuables were hidden. “I saw him while he was thus tortured to death. The shocking scene is to this day fresh in my mind, and I have often been overcome while thinking on it,” Smith related toward the end of his long, difficult life.

From there, the young Smith was made to walk what he said must have been 400 miles to the coast, at times carrying the gun of one of his captors, at other times balancing a heavy grindstone on his head. The older captives were pinioned and bound together into what slavers called coffles from which escape was close to impossible.

In this way, Smith’s account is brutally similar to narratives by Africans dating back to the 15th century, when Portuguese slavers helped supply the Spanish empire in the Caribbean and South America with people to dig for gold and raise crops and livestock. Even a century after Smith’s capture, after slavery had finally been ended in New York, the path from freedom to bondage remained essentially the same.

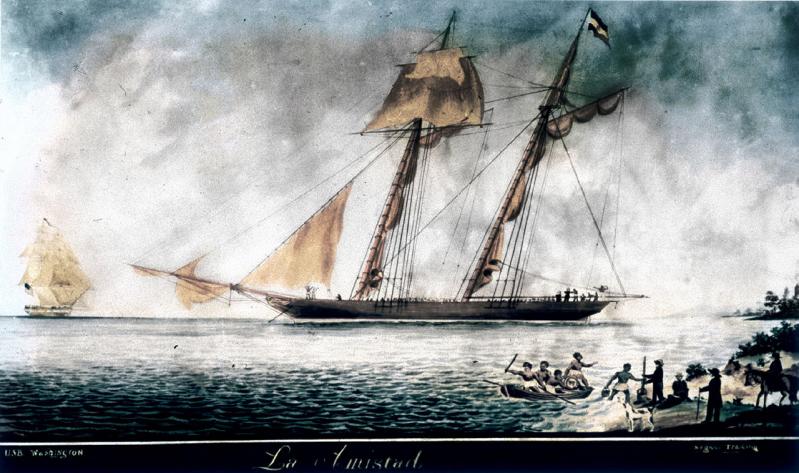

Near the end of August 1839, Cinque, a young rice planter from the Mende region of Sierra Leone, was on the beach on Fort Pond Bay in Montauk when several Sag Harbor men accosted him. This marked the start of a legal and moral battle that reached the United States Supreme Court for the former captives who had mutinied aboard La Amistad, a Spanish-flagged sailing ship bound from Havana to Puerto Principe.

Held in Connecticut while their fate was decided in court, Cinque and the other surviving Africans who had been aboard La Amistad provided accounts that are rich with detail. He described his capture while traveling, and how his right hand remained tied to his neck during a 10-day trek to the coast, where he was sold to a Spaniard. Eventually, he and the others were forced onto a ship that he said might have held as many as 500 captives, the men crammed against one another in a fetid space below deck in which they could not stand and had to crawl to move about as they sailed across the ocean to Cuba. Whippings were frequent. Captives died at sea and were thrown overboard in the morning.

Transferred to La Amistad, Cinque and the others rose up, killed the captain, and took over the ship about four days out from Havana.

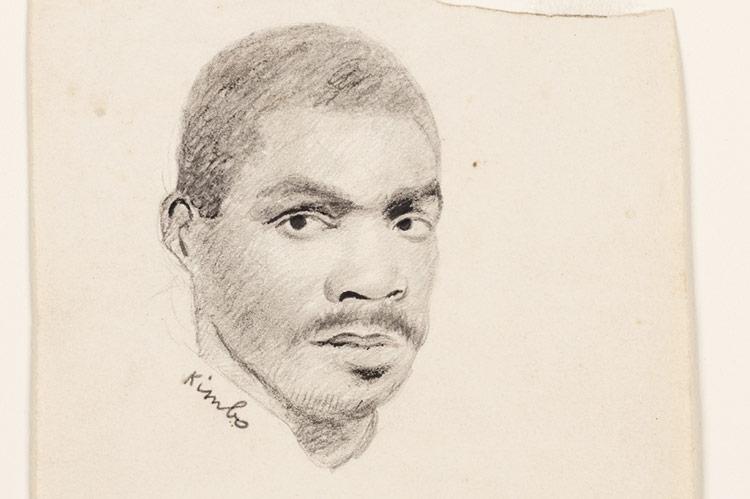

While waiting on their case to be resolved, the former captives were more than eager to tell their tales. Gilabaru was taken in the Bandi region as he walked to another village to buy clothes. A rival village attacked Fuliwa’s town and he was made a prisoner, then sold into slavery. Teme, a young girl, was taken when a party of men broke into her mother’s house. Kimbo had been enslaved to a king of his home region, then sold and sold again before being loaded onto a waiting slave ship at Lomboko.

Suma, or Shuma, had been taken during a war; he told an interviewer that he could count in the Mende, Timmani, and Bullom languages. It was four months before he arrived at the coast.

The Supreme Court eventually ordered the Amistad captives freed.

After many years of hard work, Venture Smith was able to save enough money to buy his way out of slavery, eventually owning 100 acres of land. “My freedom is a privilege which nothing else can equal. Notwithstanding all the losses I have suffered by fire, by the injustice of knaves, by the cruelty and oppression of false hearted friends, and the perfidy of my own countrymen,” he told his transcriber.

Much of the research reflected in this article came out of the work of Plain Sight Project volunteers and student interns. The project is an ongoing collaboration between the East Hampton Library and The East Hampton Star to understand the scale of slavery on the East End. For inquiries about volunteering, send an email to [email protected].

More about early Long Island:

In Plain Sight, a Long-Buried History of East Hampton's Enslaved

In Hook Mill's timbers, a present-day connection to early black America