By 1930, the superintendent of highways could not remember where the Freetown cemetery was.

It was George S. Miller’s Memorial Day routine to see about cleaning up all of the untended cemeteries in town. As Miller and his highway crew were about to call it quits, he asked the men if they thought any of the old cemeteries had been overlooked. One of them mentioned a small plot off Three Mile Harbor Road, not far from the Neighborhood House.

With some difficulty, they found it, “a tiny, forgotten collection of mounds not over 18 or 20 in all, and only one marked” Miller told a columnist for The East Hampton Star.

The lone headstone was for a freeman named Ned, “Faithful Old Negro Servant of Jeremiah Osborn, Died August 8, 1817, Age 68.”

In Plain Sight: |

Miller said he believed the small cemetery was for people freed from slavery. “And you know East Hampton people owned a good many slaves in the early days,” The Star noted. “And as long ago as that the name ‘Freetown’ must have originated; for that district which is now generally known as ‘North Main Street.’ ”

Uncertainty lingers even about the actual origin of Freetown as a place name, as well as the cemetery’s location. The predominant assumption, according to Hugh R. King, the official East Hampton Town historian, is that the area had been home to enslaved people freed around 1800 by members of the Gardiner family.

Mr. King said that he had never heard about a cemetery in Freetown and described himself as “stunned.” “What this does, to me, is give further indication that there was a thriving community in Freetown and we need to find out more about it,” he said. “It’s good and bad news, good that we know they are there, bad that we don’t know where they are.”

In early United States censuses, only the heads of households were listed. In the waning days of slavery in New York, few formerly enslaved people were counted with last names — or perhaps not in the estimation of white authorities. But there, among Plato, Rufus, Judas, and Prince, is Edward, likely the Ned on the headstone, with eight others in his home.

Adding credence to the idea that Freetown was home to the formerly enslaved are records that show Bills Gardiner, Luce Gardiner, and Cato Gardiner were black residents living at the north end of East Hampton in the early 19th century. Of course, the Gardiners were by no means the only people in East Hampton to hold fellow human beings in slavery.

Other Freetown households headed by black people included those of Isaac Right, Cyrus Dep, Sally Cuffe, Caroline Dominy, and Dence Jack. Over time many of those names disappeared and other black households appeared, including Scipio Schellinger, Peter Hand, and Dina Barnes’s.

But as late as 1810, 68 people were listed as enslaved in East Hampton, about 5 percent of the population. There were 118 free blacks.

With only two exceptions, where East Hampton’s formerly enslaved and born-free black Americans were buried is gone from memory. There is Ned’s headstone and one for Peggy in the South End Burying Ground, a small sandstone marker somewhat apart from all the others.

Richard Barons, the curator of the East Hampton Historical Society, said that, like Mr. King, he, too, had never heard of a cemetery in Freetown.

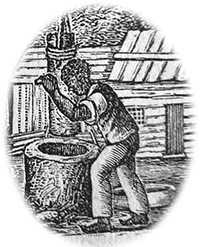

One of the possible leads comes from where Ned’s headstone was found leaning against a fence some years ago and placed by volunteers in a spot approximated to be where he might have been laid to rest. The memorial can be visited today, up a narrow path leading along a fence on Morris Park Lane in East Hampton. It is still about as legible as the day Superintendent Miller and his crew cleaned around it. Ned had been a member of the East Hampton community before his death in 1817. He swept the town church, hired by the trustees for a number of successive years, and some years he was hired to ring the church bell, too.

The East Hampton Library has a land deed of sale between Jeremiah Osborn and Ned in its collection, but, though the deed bears Osborn’s signature and those of two witnesses, neither Ned’s signature nor mark appears, and there is a blank where the price for the half-acre would have been. Suggesting that the deal might not have gone through, there is no matching property tax record in subsequent assessment rolls.

Slavery was not even in its final decade in New York by the year Ned, or Edward, perhaps, died. Emancipation was painfully slow for the enslaved; a 1799 law provided freedom for children born into slavery after July 4, 1799, when they turned 25 for women and 28 for men. An 1817 law extended backward to include all enslaved people, but slavery continued to be legal in the state until July 4, 1827. Despite the state law, the last known record of an enslaved person in East Hampton comes from 1829. It is a bill of sale for a girl named Tamer, who was 14.

Much of the research reflected in this article came out of the work of Plain Sight Project volunteers and student interns. The project is an ongoing collaboration between the East Hampton Library and The East Hampton Star to understand the scale of slavery on the East End. For inquiries about volunteering, send an email to [email protected].

More about early Long Island:

In Plain Sight, a Long-Buried History of East Hampton's Enslaved

In Hook Mill's timbers, a present-day connection to early black America

Historical Voices Tell Story of Enslaved in North

Accounts by people of African heritage whose paths crossed Long Island at one time or another provide glimpses of what their lives were like. They tell a story of brutality, deprivation, and, above all, resistance.