Peter had been living in Southampton for some time in February 1659 when he was offered a deal.

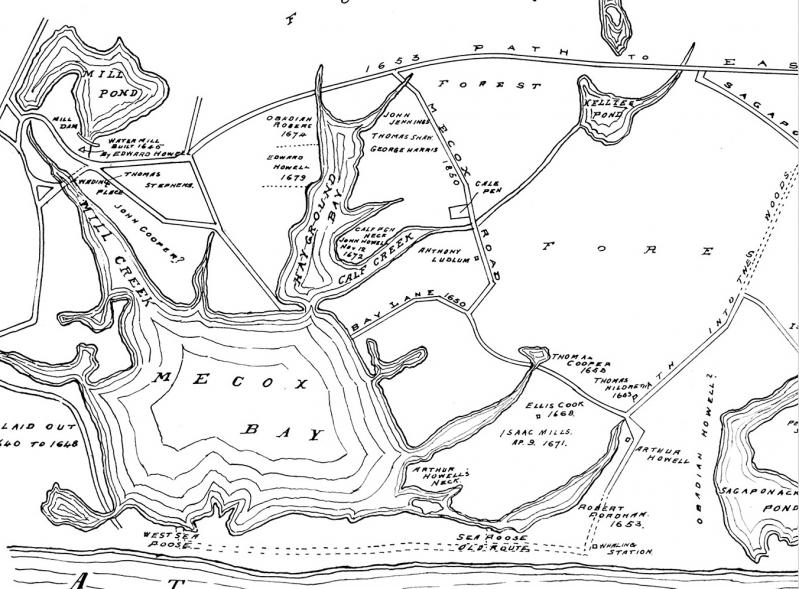

“Peeter the Neigro,” as he appears in handwritten town records, evidentially a free man of African heritage, was asked to move off land he occupied in present-day Water Mill. In exchange, he would have three acres on the far side of Mecox Bay, close to the head of Sam’s Creek.

Today, the place where Peter may have farmed and lived, more than 70 years before George Washington was born, is hidden behind privet hedges where Ocean Road jogs left toward the ocean beach.

Southampton historians have long argued that their town is the oldest established by Englishmen in what would become New York State. Southold also has staked a claim.

What may be the earliest reference to an enslaved person in Southampton Town, and therefore, English Long Island, comes from 1644, when George Wood and an Indian named Hope “consented to commit carnal filthiness together.” Their child would be held in bondage until he or she was 30. Given the frequent enslavement of Indians in the wake of the 1639 Pequot War, there is ample reason to believe that Hope was in bondage.

In Plain Sight: |

Slavery in what would become New York goes back further, at least to when the Dutch New Netherland Company set up its first outpost, near present-day Albany, a generation earlier. Enslaved Africans were in Virginia in 1619 and on the Island of Manhattan five years later.

Yet the presence of people of African origin in what would become the United States goes back further still. Juan Garrido, a free black Spaniard, was with Ponce de Leon’s conquistadors when they landed at Puerto Rico in 1509.

Puerto Rico became a United States territory in 1898. The first major uprising by enslaved people in the Caribbean took place there in 1527. But a year earlier, a Spanish trade outpost in what would become Georgia failed amid disease and violent resistance from enslaved Africans.

An enslaved Moroccan identified as Estevanico, variously described as a Moor or black in early translations, was one of four survivors of a 1529 shipwreck on the Texas Gulf Coast to make their way overland to Mexico City, arriving in July 1536.

Nonetheless, Peter’s possession of land near Cobb’s “pound” (pond) before 1659 is noteworthy and raises many questions, but that he was a known figure in the community is not at issue. A contemporaneous land division in town records describes land belonging to Thomas Halsey “at ye bottom of ye mill neck next Negro Peter’s.”

Mill Neck appears to be where Edward Howell, who had owned a grist mill in Lynn in the Massachusetts Colony, set up the water mill that gave Water Mill its name.

Edward Howell was in the first nine of the Southampton “undertakers,” who together bought a sloop on which they would embark from Lynn in the Massachusetts Colony for Long Island. At nearly the same time as Lion Gardiner was setting out his farm and homestead on his Isle of Wight, Howell and the other men obtained permission to occupy eight square miles, wherever they pleased. Howell was also the enslaver of the child of the Indian Hope and George Wood.

The push eastward in the mid-1640s of which Howell’s mill was part was the first significant expansion of the town. For some reason or other, Peter’s land, after he had used it for some time, was later needed by the town. In exchange, Peter was offered the new home lot:

At a towne meeting ffebruary 20, 1659 It was granted vnto Peeter the Neigro that hee should have 3 acres of land in some convenient place by Arthur Howell his close at Meacocks, provided the Said Peter give up to the Comon that land hee hath in vse by Cobbs pound. And hee is to fence what he shall make vse of with sufficient fencing, and stande to his own damage and after he hath Done vsing the said land it is to returne to the Comon Interest.

Meanwhile, Edward Howell “hath granted vnto him the land lying within Peter the Neigre his fence adjoining to Cobbs pound after the Neigre hath Done with the vse thereof,” perhaps after the last harvest. It is notable that the plot the town fathers offered to Peter was three acres; that was the standard size of a home lot, set some years earlier.

The historian James Truslow Adams in his “History of the town of Southampton” located Arthur Howell’s “close at Meacocks” at what would be the place today where Ocean Road and Mecox Road meet. This was at the head of Sam’s Creek, a place where a well would not have to have been dug too deep to reach potable water, at the narrowest point between the upper reaches of Mecox Bay and Sagg Pond.

If Peter had taken the town fathers’ offer, he would have had Ludlows, Cooks, Toppings, and Hildreths among his neighbors. Headstones marking the graves of members of those families can still be seen in an ancient cemetery off Job’s Lane.

Where Peter came from can at this point be only a matter of speculation, though it might have been from the Dutch colony, where the enslaved made up about a third of the population.

The Dutch at New Amsterdam had then a more flexible concept of slavery than the English and most slaves were considered property of the company. In the 1640s, the Dutch West India Company offered a kind of half-freedom to some of its enslaved people. The terms under which this would be granted were onerous, nonetheless, including that the former enslaved had to pay a tax to the company and return to work for it when summoned.

Worse, their children would be enslaved, not free. These conditions would have been a strong incentive for these semi-free people to slip away and settle in another colony. Peter may have been among those who would have moved eastward.

Intriguing, too, is a decision recorded in the East Hampton records for 1676. In it, a free black man named John was given leave to continue building a house for himself overlooking the town pond, on the condition that it remain his alone. After describing the location, the record notes John might “. . . have this land for his life time in Case hee live there but he is now way to dispose of or to sell it away but if he remove from it yn it is to remain again to the towne as before.”

Land ownership, as with many rights in the New England colonies of which the East End was a part, was reserved for Europeans. Whether Peter actually made use of the land at Mecox remains a puzzle to be solved.

Much of the research reflected in this article came out of the work of Plain Sight Project volunteers and student interns. The project is an ongoing collaboration between the East Hampton Library and The East Hampton Star to understand the scale of slavery on the East End. For inquiries about volunteering, send an email to [email protected].

More about early Long Island:

In Plain Sight, a Long-Buried History of East Hampton's Enslaved

In Hook Mill's timbers, a present-day connection to early black America

Historical Voices Tell Story of Enslaved in North

Accounts by people of African heritage whose paths crossed Long Island at one time or another provide glimpses of what their lives were like. They tell a story of brutality, deprivation, and, above all, resistance.