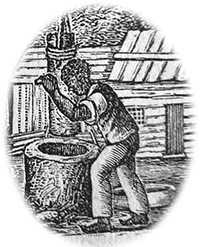

Shem was already an old man the day in 1806 when he crossed the bay to Gardiner’s Island to cut timber for a new grain mill. As the boat shoved off from Fireplace, a lingering mist and rain from a storm the night before was giving way to a mild morning. Soon, the wind came around the southwest, pushing it along. With Shem were two Montaukett boys and Nathaniel Dominy V, who was to build the mill.

Years later, one of Dominy’s grandchildren recalled that Shem, a Black man who had likely been enslaved earlier in his life, helped fell the trees while Dominy squared them with a broadax. When enough logs had been accumulated, Shem and the others used a team of oxen to drag the timbers to the beach, to be rafted to the other side.

Shem’s story is but one of the thousands that could have been told about people of African heritage in the North but who were scarcely noticed by the tellers of what passed for history. And yet, glimpses of their lives are everywhere, in account books, town records, and notations in church papers of their baptisms and deaths. There are bills of sale, wills, and manumission records. They turn up in household inventories and legal proceedings. The enslaved are, in fact, there if one simply looks.

In Plain Sight: |

In East Hampton and Southampton and across Long Island and New England, enslaved Blacks were present from the beginnings of the colony. Here, they toiled with their mostly English enslavers, though without the right to control their fate, helping to secure a toehold on the edge of a new world. There were freemen as well; one, named John, built himself a house on Main Street in 1676.

The earliest known record of an enslaved person in East Hampton comes from 1654; the last, 1830. Between those dates, about 300 enslaved individuals have been identified, a figure that is almost certainly low, perhaps representing just a third of the total. As early as 1687 there were 25 enslaved people living in East Hampton out of a population of 500. Of that total there are individual records for just seven. And yet slavery on the East End, and in the North as a whole, is not widely understood for the essential place it had in the American experiment.

Nearly everything that is known about the enslaved people of East Hampton has come out of research by the Plain Sight Project, a joint effort with The East Hampton Star, East Hampton Library, and Donnamarie Barnes, a preservationist at Sylvester Manor on Shelter Island.

One way to frame the fundamental contribution of people of African heritage is that if the white colonists built the towns that became the colonies that kicked off the royal yoke and became the United States, and if enslaved men, women, and children worked side by side with the colonists, then they too built the towns that became the colonies that became the United States.

It was not an arrangement that the enslaved had ever wanted, and resistance in ways large and small was frequent. Enslavers would go to lengths to find runaways. Advertisements were placed in the newspapers. Frothingham’s Long Island Herald announced in 1791:

Ran away from the Subscriber, about three years and a half ago, a Negro man, named Tom, between 90 and 100 years of age, had on when he went away, a snuff coloured great coat, white plush breeches, blue yarn stockings; one leg somewhat shorter than the other; about 4 feet high, Africa born, spoke very broken. Whomever will bring said Negro to his master shall receive SIX PENCE Reward, and no charges paid by LEMUEL PEIRSON.

N.B. All persons are forbid harbouring said Negro at their peril.

Local governments, themselves comprising enslavers, would get involved. For example, the East Hampton town trustees agreed to hire a man to “carry Mingo negro the servant man of Pinchus Faning to Southold & to Deliver him to his master.”

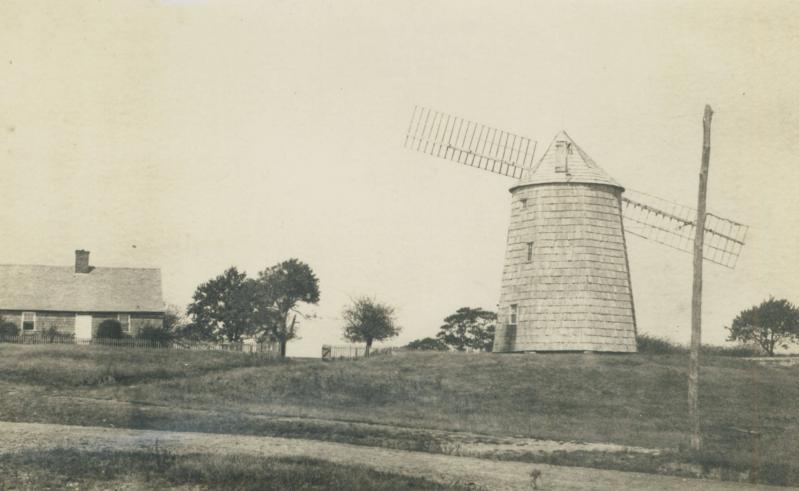

In 1806, Nathaniel Dominy, who was East Hampton’s best craftsman, joined a group of shareholders who organized as the Hook Mill Company to erect a new mill to replace one built about 70 years earlier that had reached the end of its usefulness.

It was to be a new-style smock mill at the north end of the village at the place called the Hook. But for good timber, most of what Dominy needed could no longer be found in East Hampton, larger trees having been cut into boards for houses and for the firewood to heat them. John Lyon Gardiner, then the proprietor of the island, welcomed them to come for timber, though each board and beam had its value, which was carefully tallied in one of the ledgers he kept. In addition to the wood, Gardiner recorded that the Hook Mill Company owed him by the end for 36 meals as well.

As best records appear to tell, in 1754 Shem had been enslaved to Eleazer Miller. Like some of the enslaved and free Black townspeople of the time, he was baptized and received into the town church. Miller was a man of means, and one of his sons, Burnett Miller, for many years was town clerk and was a member of the Fourth Provincial Congress and in the New York Legislature for about 35 years. Records indicating if this Shem was free in 1806 are not conclusive.

As in white families, names were reused from generation to generation among Blacks. If the first Shem was an old man in 1806, it was another Shem who lived in East Hampton about a generation later and was married to Ellen. Their house was in what was called Freetown and they had a daughter, Binah.

Jeannette Edwards Rattray, who was East Hampton’s unofficial historian during much of her adult life, speculated in 1966 that this was Shem Gardiner, one of the enslaved people freed by the island’s proprietors and who settled in that part of North Main Street or, perhaps, the son of one of them.

That one or both Shems were closely linked to the Dominys is clear. Erastus Dominy wrote in his diary at about the time of the Civil War, one day in May, “Father, Sylvanus Osborn, Shem and I down to beach fixing seine.” Another time Shem and another man were hired for a dollar a day to work on the property; Erastus explained that the high rate was because the two had furnished their own food.

Hook Mill ran until August 1879 “when it was disabled by having its iron shaft broken during a terrific gale.” It was repaired and continued to mill flour commercially until about 1914. About Shem, Ellen, and Binah — and the rest of East Hampton’s early Black Americans — much more remains to be learned.

Much of the research reflected in this article came out of the work of Plain Sight Project volunteers and student interns. The project is an ongoing collaboration between the East Hampton Library and The East Hampton Star to understand the scale of slavery on the East End. For inquiries about volunteering, send an email to [email protected].