A dull orange tint rose high above the western skyline as East Hampton was getting ready to go to bed the night the Sea Spray Inn burned to the ground. At about 9 in the evening on the 20th of February 1978, someone noticed flames coming from a crawl space and called in an alarm.

There was snow on the ground, which made fighting the fire difficult. The water supply was poor; a thin, dead-end main on Ocean Avenue gave a poor supply. Firemen tried to chop through the ice in Hook Pond but found it frozen near the shore, all the way to the bottom. A village payloader was brought in to clear a passage for a pumper truck, and a hose finally reached water near the pond’s outlet pipe. Pumpers also hooked into a larger water main on Lily Pond Lane.

Despite all this, the fire could not be stopped. In the end, some 125 volunteer firefighters from four departments were unable to save the building. A set of separate guest cottages on the Sea Spray property were not damaged in the fire.

Arson was immediately suspected. Police questioned a suspect later that winter, but the lead did not pan out. No one was ever charged in connection with the fire.

Within a year, village residents voted by a 3-to-1 majority to buy the 16-acre property and to add the land and its 10 cottages to the village’s roster of parks and recreational sites.

Soon, the village board decided instead to lease out 13 units among the cottages as summer rentals, with the tenants responsible for repairs. This, however, did not pass muster with the state, which pointed out that the village could not legally rent out cottages on parkland. It took an act of the State Legislature to solve the problem, approving an exemption that allowed the village to offer leases, with the rental income going to the budget’s general fund.

For more than 20 years, the mostly oceanfront cottages were arguably the best deal on the South Fork, starting at about $15,000 for the season. Rents crept upward over time. In 1980, the units produced $84,000; in 1999, the village took in $260,000. About $1.2 million in rental income is anticipated this year, against expenses of about $125,000. For many years the cottages had been rented by the same tenants each season, until 2010, when the village began awarding them instead to the highest bidders.

Talk of changes at the Sea Spray property has been heard around East Hampton Village in recent weeks. There have been conversations among village board members about the cottages and whether it would be advantageous to turn their management over to a private company, which would then be responsible for their upkeep. This may be considerably more easily said than done, requiring an act of the New York State Legislature.

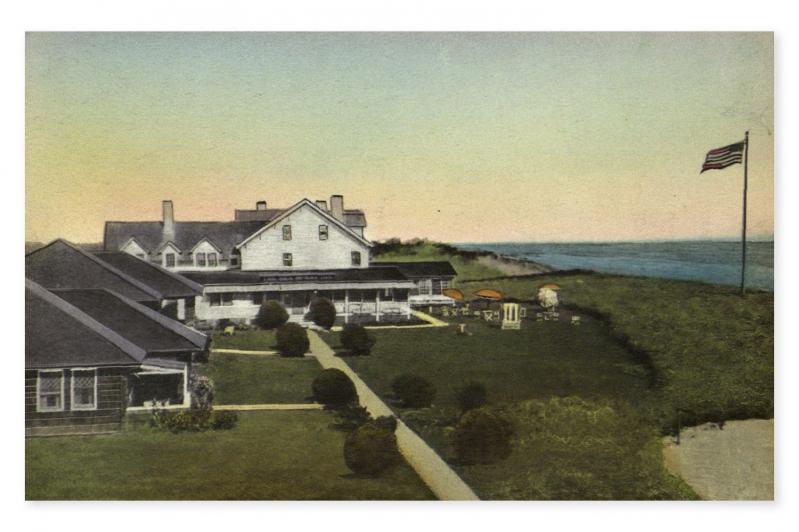

At its peak, the Sea Spray Inn could host 125 guests, who would be looked after by a staff of about 55. Its restaurant could handle as many as 166 diners at each seating. In its postwar heyday, the staff went all out on holidays. On the Fourth of July, they wore costumes and cooked bouillabaisse over an open fire in a whale-blubber try-pot supposedly salvaged from an old ship. A six-foot-long American flag was fashioned from blueberries, sugar stars, and alternating rows of onion and tomato slices suggesting stripes.

The fire’s aftermath was not the first time that village officials had eyed the property. In 1971, a crowd of angry residents had shouted down a plan that would have allowed the inn to expand to almost 370 units. In the mid-70s, its then-owner, Donald J. Clause, proposed a residential subdivision. But the village planning board dug in and recommended instead that the Sea Spray and its adjoining property be acquired for use as an expanded Main Beach public bathing facility. Price was the sticking point, however, and a deal did not materialize.

The Sea Spray had not always been an inn, nor had it always been near the ocean. It was built for Josiah Mulford, sometime in the first part of the 19th century, on East Hampton Main Street, as a house. In the 1860s, it became a hotel under the management of William Gardner, who had been the Montauk Lighthouse keeper. Averill Dayton Geus, writing in The East Hampton Star in 1959, noted that Gardner “liked gaiety and held oyster suppers and dances at his establishment.” It is thought that the celebrated landscape painter Thomas Moran and his wife, Mary Nimmo Moran, also an artist, had their first stay in East Hampton there. W. Cohu White became its manager in 1886 and gave it the name Sea Spray, perhaps after Cornelia Huntington’s 1855 East Hampton novel of the same name.

E.D. Terbell bought the Sea Spray in early 1902 and had it moved to the dunes as a summer house. The work began in February, but was delayed because of snow, and for weeks the house sat on rollers in the street. When the process began again, trees along the narrow section of Main Street at the south end near Town Pond had to be cut back or removed entirely to let it pass. Thomas Moran was among those that summer said to have threatened to shoot anyone who touched his silver birches. Instead, a fire hydrant at the Woods Lane corner was removed. The house finally reached its new foundation in mid-May.

The cottages came along later, after the house had again become a hotel. The Star reported in 1914 that Geo. Eldredge & Son were building two bungalows to face the ocean. George A. Eldredge, a self-taught architect and builder, designed the cottages, as he had done for a number of East Hampton summer houses in the 1890s and early 1900s. Among his commercial projects was the E.J. Edwards Drug Store on Main Street, a gambrel-roofed building that now houses The East Hampton Star.

Donald Hunting, who was associated with the Sea Spray Inn on and off for 25 years until 1969, recalled that World War II had been a boon to the inn, what with travel opportunities strictly limited. Managing a combined staff and guests of roughly 175 people during the war was a challenge, though. The inn’s gasoline ration allowed just one trip each day into the village, and if something was forgotten, they did without. There was a victory garden where a parking lot is today, and even a pigpen. Mr. Hunting told a Star interviewer in 1998 that the uneaten food and kitchen scraps from 500 meals each day kept the pigs very well fed.

Arnold Bayley was the owner and innkeeper during that time, and a person of great thrift, Mr. Hunting said, “who would fly into New York in his own private plane, register at the Plaza, and be found by his bedroom window darning a sock.” One reason so much of the Sea Spray property and 1,800 feet of beachfront remained undeveloped is that Bayley “was such a conservative Yankee that he would only expand the facilities from profits.”

Ever since the village voters agreed to buy the property in 1979, there has been recurring worry that the cottages might someday be expanded. About 15 years ago, two nearby neighbors sued the village, asking a state judge to rule that the site was “held in trust for the residents of the village for beach and park purposes only.” The suit ended in a settlement, in which the village promised not to sell, lease, or otherwise transfer the Sea Spray property without a public hearing, and that any plan to do so would require approval by the State Legislature, as had the original rentals. Then-Mayor Paul F. Rickenbach Jr. signed the formal declaration in 2008.