When a plaque honoring Lt. Lee A. Hayes, a World War II Tuskegee airman, was unveiled on Saturday at the youth park now named for him in Amagansett, the event was both a celebration of an East Hampton hero and the centerpiece of a Hayes family reunion of epic proportions.

Almost a century to the day after he was born, grandchildren, nieces, nephews, and cousins who had never met before came together under a brilliant blue sky to honor the man who would have turned 100 on Monday.

Mr. Hayes, who died in 2013 at the age of 91, was the oldest of 13 children who grew up around the corner from the park on Town Lane. The family calls the area Hayesville, because so many Hayes descendants made their homes there over the years. It was on Town Lane that Lieutenant Hayes built his own house after the war, and where he remained for the rest of his life. He passed what is now the park every day, on his morning walks down Abraham's Path to American Legion Post 419 at the corner of Montauk Highway. The park was renamed in his memory last year.

Fittingly, people gathered first at the American Legion on Saturday morning, to retrace his steps with what family organizers dubbed a Walk in the Path of an American Hero.

Dozens of relatives and friends, who had come from as far away as Texas and Georgia, wore black T-shirts bearing a photograph of Mr. Hayes in his flight gear, taken during the war. "Say Hayesville!" someone called out as they posed together for a photo before setting off.

A contingent from the Tuskegee Airmen Motorcycle Club and a color guard from Local Union No. 3 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers were on hand to lead them down Abraham's Path, which was closed to traffic. A police escort followed.

"We're trying to extend the legacy of the Tuskegee airmen and the contributions they made," said Don Hudson, a member of the motorcycle club. The Tuskegee airmen were the Army Air Force's first Black pilots, trained at the Tuskegee Airfield in Alabama during World War II when the United States military was still segregated.

At the youth park, speakers remembered Mr. Hayes, his military service, the challenges he faced after the war, and the legacy he left as the patriarch of an extended family.

Mr. Hayes dropped out of school to help support his family. Dissuaded by his mother from enlisting, he was eventually drafted into the Army in 1943. "Once he learned the Army was administering entrance exams for the Air Force, he jumped at the opportunity and scored one of the highest grades in the group," despite not having the two years of college normally required to become a military pilot, according to a biography on the town's website.

"He was soft-spoken and self-educated," said Rodney Hillman, a relative and Army veteran who spoke at the park on Saturday.

Mr. Hayes became a member of the 477th Bombardment Group of the Tuskegee Airmen. He trained as a bombardier in Texas and then returned to Tuskegee as an officer for pilot training. The war ended before he could fly in combat, Allison McGovern wrote in the biography on the town's website.

"After the war, he wanted to fly commercial aircraft, but was turned down," Mr. Hillman said.

"He once joked that he could fly 3,000 feet in the air and drop a bomb in a garbage can," but couldn't get a job as a commercial pilot, said Raymond Melville, a retired senior assistant business administrator with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Works Local Union #3. Mr. Hayes had spoken to the union about his experiences, and it made a strong impression on the members, Mr. Melville recalled.

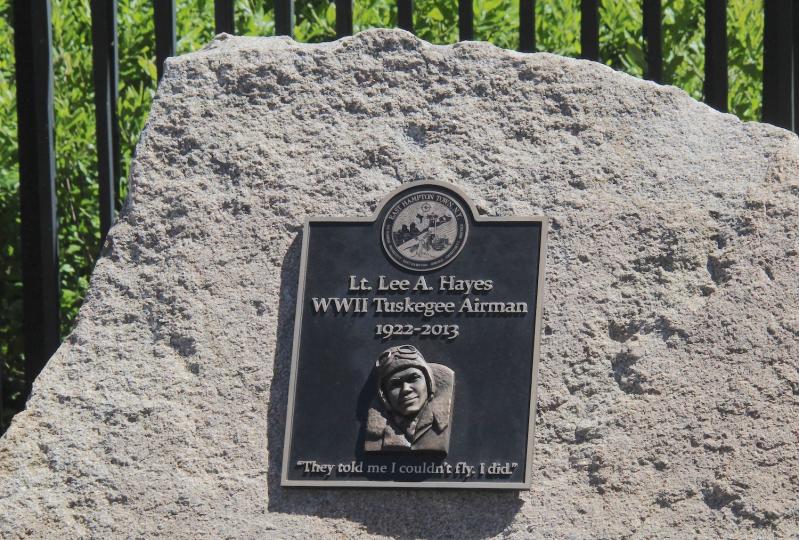

The plaque now affixed to a large boulder at the park's entrance includes a likeness of Mr. Hayes as a young aviator, with the quote: "They told me I couldn't fly. I did."

"It is an honor to recognize not only one who has walked with God, but who has flown with God," said the Rev. Walter Silva Thompson of Calvary Baptist Church in East Hampton, who called Mr. Hayes "an American hero" and "a giant of a man."

"He was allowed to serve his country in a way that had never happened before," but was denied the opportunities he deserved both inside and outside of the military, said East Hampton Town Supervisor Peter Van Scoyoc, whose office worked closely with the extended Hayes family to organize Saturday's event. Looking back at the racism Mr. Hayes encountered, both in the military and after the war, Mr. Van Scoyoc acknowledged to the crowd that there was much work still to be done in America.

"Our democracy is not a one-and-done," he said. "Today we walked in the footsteps of an American hero . . . and as we go forth today, let us pledge to be more tolerant of others, to rejoice in our differences, to strike down the barriers that prevent individuals from achieving their full potential."

Mr. Hayes became a builder rather than a pilot, and helped many of his relatives by "building houses for them when they couldn't obtain mortgages because of the color of their skin," said Audrey Gaines, a close family friend. (She thinks of herself as the 14th Hayes sibling, she said.) A former town youth services director, Ms. Gaines was instrumental in getting the youth park built.

Mr. Hayes was a charter member of the Calvary Baptist Church, an East Hampton Town Democratic Committeeman, and an important advocate for the hiring of the town's first African-American poll-watcher and its first Black postal service employee.

Part of what makes America great, Representative Stacey Plaskett, a family friend, told Saturday's crowd, is that we are "willing to face our wrongs" and to "try to change." Ms. Plaskett, who represents the U.S. Virgin Islands and was a Democratic House impeachment manager last year, was a college roommate of one of Mr. Hayes's nieces, Aleta Williams.

On the eve of Juneteenth, the federal holiday celebrating the emancipation of the last enslaved Africans in the United States, Ms. Plaskett credited Mr. Hayes and his fellow airmen with "breaking down barriers that no slave or even his parents could have imagined."

"You have done your duty to your ancestors," she said, addressing the people at the park, and "you need to work for the future now. . . . We need you on the front line, voting, raising your voice. . . ."

"The baton has been passed, and it's now critical for us to pick up that baton and think about the way forward and what sacrifices we need to make and what battles we need to fight," Ms. Williams said by phone on Tuesday from Washington, D.C.

Former President Barack Obama was invited to attend the dedication. He could not, but his scheduling department told Ms. Williams by email that he "is deeply moved by the impact you, your uncle, and your family have had on your community."

For family who had come from near and far, the weekend included the dedication Saturday morning, a dance on Saturday night, church at Calvary Baptist on Sunday morning, and a beach day at Maidstone Park on Sunday afternoon.

"We have very strong roots in this community and it was a wonderful homecoming," Ms. Williams said. The fact that it all turned out so well, with the weather cooperating to boot, was a sign to her that Mr. Hayes and his siblings were looking down on the festivities. "We are all completely convinced that the 13 plus our grandparents had a hand in that."

Jolyn Hopson, a niece whom Ms. Williams credited with "seeding the idea" of the park dedication, put it best on Saturday morning as she called out to her extended family: "You should be honored to call yourself a Hayes!"

With Reporting by Judy D'Mello