It has been three years since commercial baymen and recreational harvesters have enjoyed bountiful catches of bay scallops in local waters. The season, which runs from early November to the end of March, has been a bust for all.

The struggling bay scallop population, which was first hit hard by a devastating brown tide that appeared over a three-year period commencing in 1985, has witnessed another round of greatly diminished catches that started in 2019. It was another catastrophic blow.

By all accounts, the highly savored scallop is very much imperiled. But can the popular bivalve, which lives for upward of 22 months, be saved for future generations to enjoy? Science, as well as a nudge of assistance from Mother Nature, may ultimately play a key role in the return of once-plentiful landings.

“The bay scallop is currently in a very precarious position,” Dr. Stephen Tettelbach, a Cornell Cooperative Extension scallop specialist, said in a presentation on the current state of the bivalve on Friday afternoon at the Ram’s Head Inn on Shelter Island. “Right now, the news is not good, but there could be some hope down the road. Time will ultimately tell the story.”

Dr. Tettelbach, who has studied the roller-coaster-like rise and fall of the scallop population for more than 35 years, said that the most recent adult die-offs, which typically occur a few weeks after scallops begin to spawn in early to mid-June, were due to a combination of several complex environmental factors. He said the physiological stress of spawning, in conjunction with higher water temperatures, lower dissolved-oxygen levels, and the discovery in 2019 of a coccidian protozoan parasite have all played a role.

“Unlike clams and oysters, scallops are, unfortunately, much more sensitive to various conditions when they are in the process of spawning,” he said. “Spawning itself is very taxing on scallops, plus when you add all of the other stressors, it’s why in the summer months we have witnessed the die-off of so many adult scallops.”

In 2019, Dr. Tettelbach said, about 95 percent of the adult scallop population succumbed during the summer, when waters were warmer. In 2020, the figure was even worse: a 99-percent die-off. The results for 2021 were marginally better; approximately 10 percent of adult scallops managed to survive.

“It’s possible that with the slightly improved numbers we saw last year, that the scallop is starting to build a natural resistance to disease and other external factors,” he observed. “As well, it’s great that the juvenile recruitment remains excellent. Over the past three years, we have seen more baby scallops than ever before in the seven dive locations we observe.”

“They are very hardy and resilient,” he added. “It’s just unfortunate that so few of the adult scallops survive after they spawn. We, sadly, are currently in a loop.”

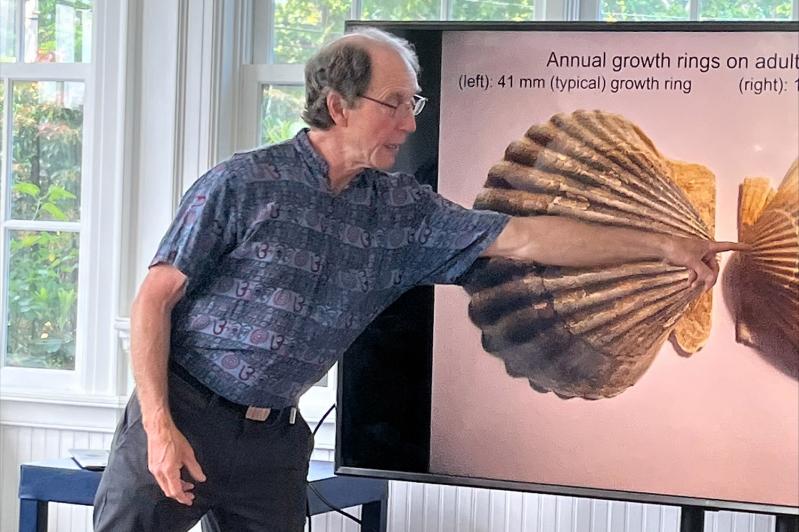

Last summer, scientists at Stony Brook University received $240,000 from New York Sea Grant to research a selective scallop-breeding program, in partnership with Cornell Cooperative Extension. That program, said Dr. Tettelbach, will evaluate which scallops fare better under environmental stress. Last fall, he and several colleagues donned scuba gear to search the bay bottom for the oldest living scallops, on the theory that those specimens had been able to withstand all of those factors that killed a vast majority of their peers.

“We spent many hours diving, and came up with about 45 of the oldest living scallops we could find, to begin the selective breeding program,” he said. “What we need to know is whether the resistance to those combined stressors is genetically dictated. If so, then there is a chance we will be able to identify those scallops that are resistant to such stressors, and [the knowledge] can then be ultimately used for aquaculture restoration.”

It will likely take a few years to see the results of the study, he said, but he has his fingers crossed. “It’s been a long, winding road for our bay scallop,” he said. “We want to restore what we once had, and hopefully, science will play a