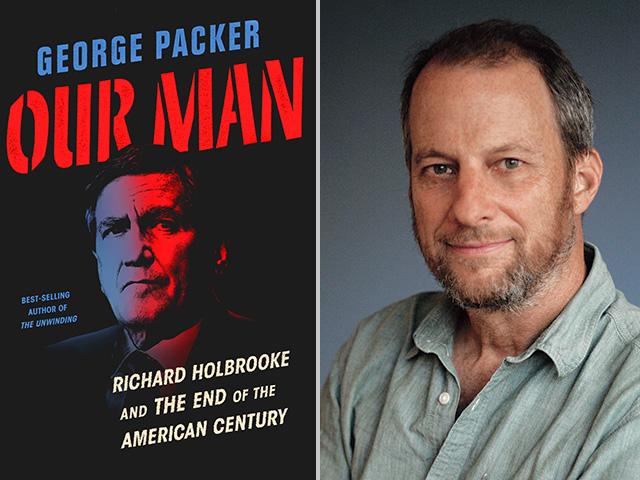

“Our Man”

George Packer

Knopf, $30

Even those who admired Richard Holbrooke, and there were many, would have to agree: The dedicated diplomat often went too far, and finally fell short of his ultimate goal.

“The world will look to Washington for more than rhetoric next time we face a challenge to peace,” the soon-to-be U.S. ambassador to the United Nations wrote presciently in “To End a War,” his 1998 account of historic peacemaking in embattled Bosnia.

“And Washington, no doubt, will look to Mr. Holbrooke — as civilian, U.N. ambassador, or some Democratic president’s secretary of state — for what this book shows to be his remarkable energy, imagination, persistence, and passion for the most daunting diplomatic crises of our time,” predicted a review in The East Hampton Star (mine) of the distinguished Bridgehampton resident’s memoir.

But that forecast, really Holbrooke’s dream, never fully materialized. Changing political tides, plus the flip side of his passion and persistence — a history of leaks, lies (personal and professional), libidinous larks (even with a best friend’s wife), and shameless self-promotion — often left him on the sidelines, albeit well-paid Wall Street sidelines. And just short of the cabinet role for which he always felt destined.

A sad truth lingers from “Our Man,” George Packer’s warts-and-all but loving biography: Of all the foes Holbrooke faced across diplomatic negotiating tables and within the upper echelons of American government — with the Agency for International Development in Vietnam, as staff assistant to two U.S. ambassadors there, assistant secretary of state for Asia, and later Europe, ambassador to Germany and the U.N. — his worst enemy was frequently himself.

“Holbrooke? Yes. I knew him,” Mr. Packer writes. “I can’t get his voice out of my head. . . . Calm, nasal, a trace of older New York, a singsong cadence when he was being playful, but always doing something to you, cajoling, flattering, bullying, seducing, needling, analyzing, one-upping you — applying continuous pressure. . . .”

It’s no little irony that the fatal bursting of an aneurysm in Holbrooke’s aorta began in the very office he so coveted, where then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was already under orders to start bringing the ax down on his long, dramatic career.

Ironic, too, that a man even many detractors had to admit was among the best American diplomats could also be so undiplomatic and impolitic with colleagues — so heedlessly, needlessly abrasive to inferiors and superiors — that he became anathema to them.

“He’s such a pain in the ass — nobody can stand him,” Vice President Joe Biden advised Les Gelb, a mutual friend and foreign policy veteran.

But in what seems to be a great State Department tradition of bureaucratic backstabbing and counter-stabbing, Holbrooke even from the grave has some revenge. Mr. Packer quotes a long diary note (“I want you to hear his voice one more time”) including the argument that Holbrooke, as Hillary’s special representative for war-plagued Afghanistan and Pakistan, made to Biden about guaranteeing the rights of Afghan women once Taliban forces were beaten or bargained with.

Biden erupted, Holbrooke recounts: “I am not sending my boy back there to risk his life on behalf of women’s rights, it just won’t work, that’s not what we’re there for.” Not a great moment for Joe from the current #MeToo perspective.

Mr. Packer paints Holbrooke not only as a creative and realistic representative of American interests and humanitarian values, but also as embodying (another form of representation) the spirit of our nation in a particular arc of its history — from sole superpower after the Cold War, convinced of its military and moral might, to defeat in Vietnam and subsequent doubts and division over handling challenges from the Balkans to Somalia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and beyond.

The future diplomat was not to the manor born. But close enough that at Scarsdale High his best friend was the son of the State Department veteran Dean Rusk, then president of the Rockefeller Foundation, later John Kennedy’s secretary of state, and in between a kind of surrogate father when Holbrooke’s own dad died, never mentioning the family’s Polish-German Jewish origins.

Upon immigrating to the U.S., Dr. Daniel Golbraich found the sound-alike name Holbrook in a Manhattan phone book and added an “e” for good WASP measure. The secret was kept from Richard for years.

And it was Rusk who swore him in at the Foreign Service Institute in July 1962, inscribing a volume on diplomacy: “With warm congratulations to my friend Dick Holbrooke as he enters upon the greatest profession.”

In Vietnam Holbrooke learned the importance to successful counterinsurgency of shirtsleeved work with folks at paddy level, the limits of firepower or coup-plotting, and the limitless tendency toward deception and self-deception when it came to bad news going up a chain of command — all the way to L.B.J.’s White House.

“I have my doubts, getting deeper and deeper, about our basic approach here,” he wrote at the time. A visit by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara “added weight for the exponents of Victory through Air Power — the Air Force, and the armed helicopters. I feel this is a terrible step, both morally and tactically.”

In the case of Bosnia, however, and Serbian genocide of the Muslim population that Holbrooke had mixed with personally in Sarajevo — as a civilian on behalf of the International Rescue Committee — air power seemed critical.

In early 1993 he proposed bombing Serb targets and permitting weapons in for the Muslims’ defense. But that was out of tune with civilian and military leaders of the incoming Clinton administration. “If I don’t make my views known to the new team, I will not have done enough to help the desperate people we have just seen,” Holbrooke wrote to himself. “But if I push my views I will appear too aggressive. I feel trapped.”

Indeed, it wasn’t until 1994, deep into the third bloody year of war (10,000 dead in Sarajevo alone), that Holbrooke began to gain the leverage necessary for what would become his famous peace deal in unlikely Dayton, Ohio.

By then Clinton’s ambassador to Germany, Holbrooke agreed to step back in rank and become assistant secretary of state for Europe, including the Bosnia problem, amid vicious bureaucratic division over that issue, and over Holbrooke himself.

And it wasn’t until the summer of 1995 that Secretary of State Warren Christopher actually gave Holbrooke the green light — finally realizing, as Mr. Packer writes, “that the same traits of character that made [Christopher] shudder — the self-dramatization, the aggressiveness — would be more than a match for the Balkan warlords.”

It was a Hail Mary pass with Holbrooke as football — or fall guy.

He got a continuation of U.S.-NATO bombing, though it was killing Serb civilians as well as fighters, as pressure to finally win acceptance in Dayton of redrawn boundaries and borders. That gave the Bosnians, Serbs, and Croats all enough ground gains that their leaders — after 20 days of bluffs, bullying, and nonstop negotiating — could live with.

“A kind of relentless harassment of the parties into concessions that they were not ready to make unless pressured by the United States with the credible threat of the use of force,” Holbrooke judged, though the deal was beginning to fray.

“It seems inevitable now that he would end in Afghanistan . . . a final circular logic to it,” Mr. Packer writes. For what seemed to start as a good war, provoked by the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and meant to wipe out Al Qaeda and its Taliban host, had become a quagmire not unlike Vietnam: rural insurgency, corrupt and unreliable government, cross-border enemy sanctuary (in Pakistan).

But in his early, only meeting with Barack Obama, Holbrooke was overly self-serving and focused more on State Department process than the tough policy choices that concerned the newly elected president. Others in his administration had little time for the lessons from Vietnam Holbrooke kept repeating.

He had, however, forged good relations with Hillary as a candidate, and she got Obama to let her have him as “a strong civilian counterpart to the military effort in Afghanistan — a diplomat who could match David Petraeus, the four-star general who commanded U.S. forces.”

Not surprisingly, Holbrooke’s expansive vision of the problem — and of his own mandate — broadened to include Pakistan, a dubious ally, therefore its nuclear archrival India, and even Iran, whose influence in western Afghanistan he’d witnessed.

It drove some abroad and at State crazy. And Holbrooke’s strategizing and charm were less than fruitful in Kabul and Karachi despite exhausting personal visits, even a potential channel to the Taliban leader Mullah Omar. “How can we lose when we’re so sincere,” he scribbled, the line he recalled from a Vietnam-era “Peanuts” cartoon.

Holbrooke himself was in “fairly typical” shape for 67, Mr. Packer writes. But he had paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (rapid, erratic heart rate), and was on Toprol for blood pressure, Coumadin for clotting, Zeta and Niaspan for cholesterol. Every few years he had to be “cardioverted” with electric shocks to restore normal heart rhythm. And then a scan showed the aortic aneurysm, but only watchful waiting was prescribed.

Back in Washington from Kabul, at dinner with Career Ambassador Frank Wisner Jr., a colleague since Vietnam, Holbrooke scratched his nose on a clamshell and lost so much blood that it took two napkins to sop up. “What are you doing this for? Get the fuck out,” Wisner urged.

“I will. I will,” Holbrooke said, yet persisted — crashing meetings in Clinton’s office, being eased out by young staffers, left out of Obama’s Afghan visit and a NATO summit.

Finally came the formal meeting with Clinton herself, Dec. 12, 2010. “Oh my God, Richard, what’s happening,” she cried as his face turned “so furiously red it was cartoonish,” Mr. Packer writes. Holbrooke, bewildered: “. . . Something horrible. . . .”

Then it was a desperate rush to the medical office, terrible chest pain, an ambulance to George Washington University Hospital, Hillary’s personal doctor in attendance, and 20 hours of surgery from which he never awoke.

Burial at Arlington was requested but denied because Holbrooke never served in the military. It took his third wife, the writer Kati Marton, five years to part with his ashes, finally buried in a nearby South Fork cemetery.

Mr. Packer doubts that Holbrooke, with limited influence left in D.C., could have solved the Af-Pak puzzle. And you can feel his own heart giving way at the end.

“That’s all I have to tell you,” he writes. “I’ve gone on longer than I meant to. There was too much to say . . . of a life lived as if the world needed an American hand to help set things right. . . . But now that Holbrook is gone, and we’re getting to know the alternatives, don’t you, too, feel some regret? History is cruel that way. He loved it all the same.”

David M. Alpern interviewed Holbrooke, McNamara, Gelb, and others in this book over more than 30 years as host of the “Newsweek on Air” radio program (from which he will play key clips at the Rogers Memorial Library in Southampton in July). He moderates monthly discussions on foreign policy for the John Jermain Memorial Library in Sag Harbor.

George Packer is a staff writer for The Atlantic.