East Hampton straddled two worlds in the summer of 1969.

In one of them there was Vietnam, and men walking on the moon, and Woodstock, and the Manson murders, and Stonewall. The civil rights movement was in full swing and war protesters were arrested in cities across the country, even as the words “peace” and “love” came to define the era.

In the other world, a small beachfront town was still small enough that almost everyone knew everyone else, for nine months of the year anyway. Summer was starting to be a different story. Current events were on people’s minds, but it was largely business as usual here. The town had only recently seen its very first bank robbery.

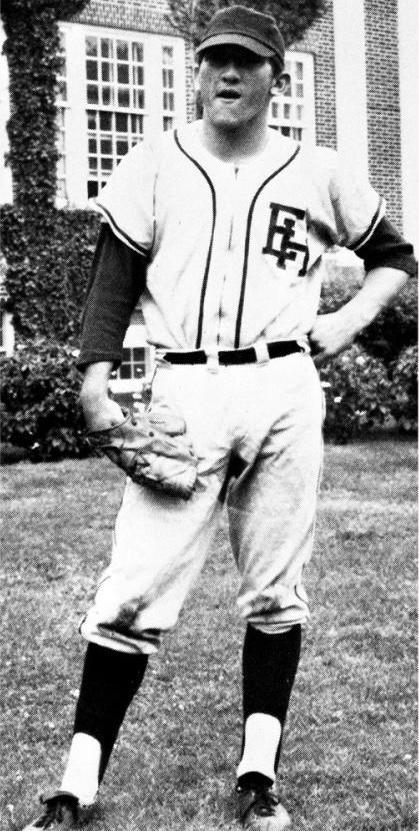

“Every night on television, the news channels covered the war in Vietnam — how many people were killed, how many troops were deployed,” recalled Larry Cantwell, a lifelong Amagansett resident and former East Hampton Town supervisor. “I think everyone during that year was taken by both the protests of the war and the war itself, the civil rights movement, people being killed in the streets.” He graduated from East Hampton High School in ’69, and said that for his senior class, “the events of the world that were occurring at that time were a big influence on you.”

Mr. Cantwell went on to C.W. Post College and did some traveling before returning home. “I learned that it was okay to be antiestablishment, which is ironic in that I spent 42 years as a public servant,” he said.

A look through the archives of this newspaper and conversations with people who were here at the time paints a pretty clear picture of how things have — or have not — changed.

Beach parking stickers had only recently come into being in 1969, and were causing confusion over which beaches were the town’s and which the village’s. “Parking System Working?” The Star wondered on July 10, after the big holiday weekend.

On June 5, the paper reported that East Hampton Town had hired its first black police officer, Robert David Cooper, a 27-year-old former grocery store stock clerk. “Police Chief John Henry Doyle said he was ‘very pleased’ with the board’s action, and added that he had been trying to persuade Mr. Cooper to join the town department for more than a year.” (Efforts to reach Mr. Cooper this week were unsuccessful.)

Mr. Cooper was hired at first as a temporary patrolman at a salary of $6,600, which puts in perspective the magnitude of the $4,500 that Harry G. Lester of East Hampton won in the state lottery a few weeks later. The “big, smiling, friendly man who works as a painter here” had bought the ticket in Riverhead, and told a reporter on July 24 that he planned to add onto his house on Cedar Court. (People here today remember that Mr. Lester moved to Alaska some years after he collected his winnings.)

On July 3, under the headline “Taxpayers Protest Rentals to Groups,” The Star wrote that “the town board was beseeched at its meeting yesterday by members of the Amagansett East Association and others to do something about curbing group rentals.”

“These people are operating a business in a residential zone,” Dr. Wayne Barker told the board members. A petition opposing group rentals, with 139 signatures, was presented to Charles T. Anderson, the town clerk.

Irene Silverman, an Amagansett resident and longtime editor and reporter for The Star, covered the “grouper” issue up close and recalled numerous ads running in The Village Voice for “alternate shares,” meaning every-other-weekend use of a shared bedroom.

“By the late ’60s, group houses were concentrated in the Beach Hampton section of Amagansett, down in the dunes east of Atlantic Avenue,” she said. “People would congregate at Asparagus Beach, which got its name because at 4 in the afternoon, all the singles who didn’t have dates that night would stand up and look around at each other, like asparagus stalks. That was the story, anyway, but there was truth in it. The families used to be on one side of the lifeguards and the singles were on the other, and you could see what was happening.”

“There may have been a sense of live-it-up-before-we-die,” Ms. Silverman said. “These kids were kids, men in their early 20s who were probably terrified of getting drafted.”

“Under Trying Circumstances”

Leslie Porte was to wed Nathan Schenker on Aug. 21 at the estate of her aunt, Phyllis Newman, on Georgica Road, but the wedding was very nearly postponed when the Tudor-style house caught fire as caterers prepared the food. The couple were married under a tree a distance away as firefighters sprayed water on the flames. Some 100 wedding guests and about that many goggle-eyed passers-by looked on.

Brian and Prudence Carabine of East Hampton were married that summer, too, under similarly challenging circumstances. Mr. Carabine’s brother had been in a car accident on the way to the ceremony and, as the guests and wedding party waited at the church in Southampton, a Jewish bridesmaid who had tired of the heat suggested they take a drink from the baptismal font.

“I wasn’t in any mood to correct anybody,” Ms. Carabine said.

About nine months earlier, Ms. Carabine, then a student at Syracuse University, had been arrested for protesting the Vietnam War. “There was upheaval, angst, political animosity, and anger on the university campuses, in the streets in Washington, D.C., on the bases, and the only thing I can compare it to is what’s going on now,” she said last week. “There was a lot of anger, a lot of frustration, a lot of feeling like, ‘Where is our country going?’ ”

Her soon-to-be husband had recently come home from the war, a Marine who remained on active duty until 1972 and was later recalled in the early ’90s to serve in the Middle East.

“I think we are not necessarily emblematic of the ’60s, because we maintain traditions,” Mr. Carabine said, speaking of himself and his wife. He remembered, though, that “we were acutely aware of what was going on in the world at that point.”

Where People Went in 1969

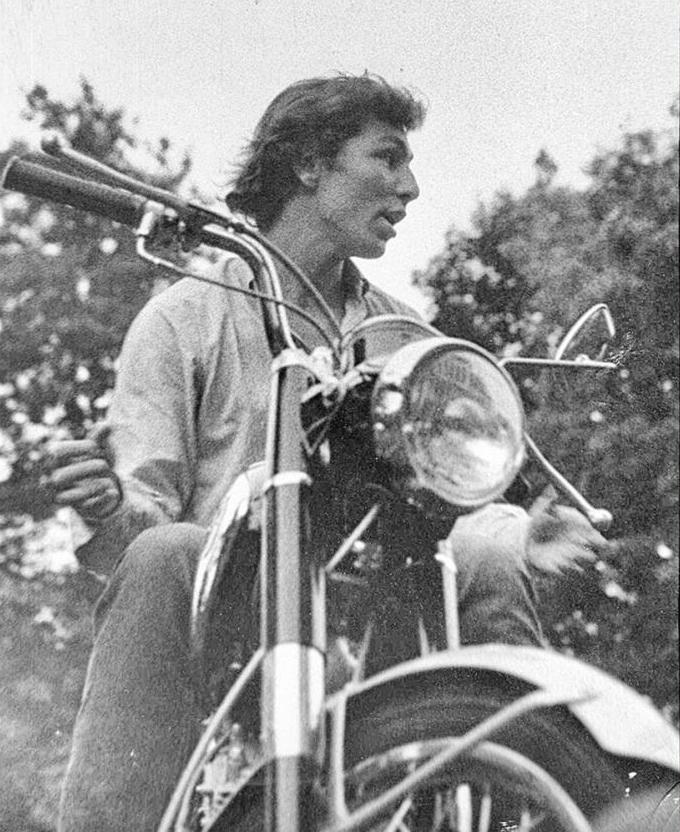

When 400,000 people went to the three-day music and arts festival called Woodstock in August 1969, Arlene Reckson of Amagansett was among them. It capped a 60-day hitchhiking trip with two girlfriends, from New York City to Nova Scotia and back.

“By the time the concert started,” she said in an email, “the lines to the bathrooms were never ending. The access to food — for days we ate free brown rice and vegetables — and water was becoming scarce. Then the rain came. We looked at each other and knew we wanted to leave. We could hear Richie Havens as our thumbs went out to hitch a ride back home.”

That was on Aug. 15. “It was after Woodstock that I switched careers from a successful shoe/fashion designer to working at Record Plant Recording Studios,” Ms. Reckson said, “where, by the time I started working, they were working on ‘Woodstock the L.P.’ ”

Todd Strasser’s novel called “Summer of ’69” is based largely on his experiences that year. A summer resident of Montauk, he was at Woodstock and the Led Zeppelin concert in Central Park, did the drug thing some, and watched the lunar landing, “which had mostly black-and-white coverage,” on a color TV.

“That was the time of life when world events really do begin to impact upon you,” Mr. Strasser said. “You suddenly got out of high school — you weren’t really in touch with reality — and then, boom, you could be drafted and sent to this war 9,000 miles away where people were dying by the dozens every day.”

Just before Woodstock, Ms. Reckson and her friends heard about the Manson family murders, which happened while they were on the road. “We had no idea about the Tate-LaBianca killings,” she said.

Fashion State of Mind

For Amy Zerner, an artist who moved to East Hampton in 1967 from an even smaller town in Pennsylvania, fashion was a highlight of the summer of ’69. She and her friends would sew their own clothes and make original outfits out of vintage clothing from the ’40s. Her father, upon hearing that the fellow who made fringe coats for Crosby, Stills, and Nash was in town in Sag Harbor, was able to convince him to make a fringed purse for her.

She doesn’t have the purse anymore, but she definitely has the same fashion sensibility. “I was always an artist, but the fashion, music, art, it was happening in such an amazing way,” she said.

She graduated from East Hampton High School that year and headed to Pratt Institute to study art. Her father died later that year, making 1969 “a big turning point in my life.”

“I think I carried on the feeling of peace and love, which was really permeating the air at the time, in my artwork,” said Ms. Zerner, who will have a solo retrospective next month in Southampton, opening on Sept. 21 at MM Fine Arts Gallery.

In her opinion, East Hampton has not changed terribly much. “It was always so beautiful,” she said. “People always say, ‘It’s changed so much, you must not like the changes.’ To me, it’s the same beauty, it’s the same special place. It’s so cultural. I don’t think there’s any other place that has this mix of artists and writers and creators.”

To the Moon and Back

David Saskas was 9 when he was photographed wearing an Apollo 11 T-shirt, kneeling next to his family’s TV set, the day the rocket was launched. The photo appeared on the cover of the July 24 edition of The Star, shortly after the lunar landing.

“It might be more my remembering it from seeing it over and over again through life,” Mr. Saskas said this week. “It was such an iconic event.”

Not everyone, though, was over the moon about it.

“Hitting the moon? What has that to do with nature? With birds and animals?” the artist Herman Cherry told The Star that summer. “Granted, it’s a fantastic event; the moon won’t come to us, but so what? Man’s mind is remarkable, but it is what he does with it that is horrible, meaningless. . . . Nobody writes poems like Keats anymore.”

Reflecting and Reuniting

Mr. Cantwell, Ms. Carabine, Ms. Zerner, and Mr. Strasser all suggested that the political turmoil of 1969 was comparable to today’s.

“In terms of my lifetime, and for students that were in high school, graduating, or in college at that time, it made the United States today a piece of cake,” Mr. Cantwell said, “and that’s saying a lot.”

Mr. Cantwell is one of the organizers of East Hampton High School’s 50th class reunion. (Fellow graduates: Email him at [email protected].) “When you grow up in a small town and go to a small school, you build more of a primary relationship with your fellow students,” he said. “You went through things together, you got in trouble together, you succeeded and failed together. That’s the beauty of growing up in a small town, and East Hampton was still a small town in 1969.”

With reporting by Christopher Walsh and Jack Graves