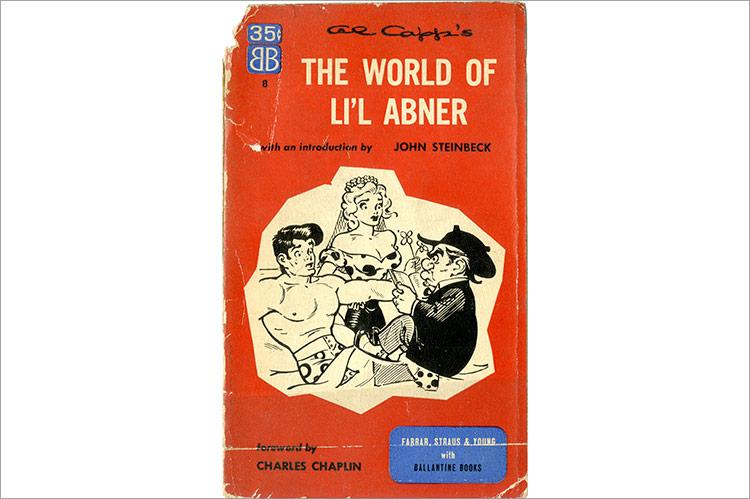

A 66-year-old paperback called “The World of Li’l Abner,” with a cover price of 35 cents, turned up recently in a pile of old books destined for an Amagansett yard sale, and if the owner, who declined to be identified, hadn’t noticed the name of John Steinbeck on the cover, it would have been sold by now for a nickel.

In the early 1950s, the years of the Korean War and Joe McCarthy, “Li’l Abner” was the most widely read comic strip in America, beating out even “Superman” and “Captain Marvel.” In 1952, one in three people in this country gobbled up the strip, with its clans of Dogpatch hillbillies, every day (in color on Sundays). Adult readers far outnumbered children.

On March 31, 1953, after the cartoonist Al Capp, creator of Dogpatch’s vast cast of hayseeds (most of whom were meant to satirize some irritating aspect of human nature), finally gave in to reader entreaties and allowed his trusting, eternally innocent, hero, Li’l Abner, to marry his sexy but virtuous girlfriend Daisy Mae — who’d been pursuing him for almost 20 years — Life magazine put the unthinkable event on its cover.

Famous actors, writers, poets, politicians, historians, and others (including Queen Elizabeth II) all loved the strip. Charlie Chaplin was a big fan. So were William F. Buckley, Harpo Marx, John Kenneth Galbraith, John Updike, Marshall McLuhan, and the author of “Grapes of Wrath,” “Cannery Row,” and “East of Eden,” later to win a Nobel Prize and have a forthcoming waterfront park in Sag Harbor, where he lived from 1952 until his death in 1968, named for him.

John Steinbeck was a huge fan of Capp’s, so much so that when asked to write an introduction to “The World of Li’l Abner,” he put aside whatever he was doing — maybe starting “The Short Reign of Pippin IV,” his only work of political satire, published a few years later — and agreed with alacrity.

“For years I have tried to get into Capp’s act,” he tells us — “have sent him wires full of humorous suggestions and directives, suggested subjects he should deal with, and he, with dreary consistency, has ignored them. Maybe my pleasure in writing this introduction comes from a sense that I have finally got into the act.”

“I think Capp may very possibly be the best writer in the world today. I am sure that he is the best satirist since Lawrence Sterne.”

Joan Baez took Capp to court in the ’60s over his character Joanie Phoanie, in an attempt to force a public retraction. The judge decided for the cartoonist, declaring that satire was protected free speech.

“Capp has taken our social structure, our economics, and examined them gently like amusing bugs. Then he has pulled a nose a little longer, made outstanding ears a little more outstanding, described it in a kind of dreadful folk poetry and returned to us a hilarious picture of our ridiculous selves but with such effective good nature that we seem to have thought of it ourselves,” Steinbeck wrote in his introduction.

“Capp seems to have no weaknesses. He tweaks with equal pressure all classes, all groups, all levels. He is the greatest collector and inspector of entrenched nonsense in the world. Cousin Weakeyes, Available Jones, Lonesome Polecat are all pretty close portraits of people we know. [. . .] The Wolf Girl is the eternal threat to the marriage of every middle-aged woman. Ol’ Man Moses is a beautiful example of all the prophets in the world — always right but always understood too late.”

Steinbeck declares at one point that Al Capp “is probably the greatest contemporary writer,” and suggests that “if the Nobel prize committee is at all alert, they should seriously consider him.”

A bit over the top, maybe, but it must have made a great quote for the publicists.

“I run into people who seem to feel that literature is all words and that those words should preferably be a little stuffy,” he continues. “Who knows what literature is? The literature of the Cro Magnon is painted on the walls of the caves of Altamira. Who knows but that the literature of the future will be projected on clouds? Our present argument that literature is the written and printed word in poetry, drama and the novel has no very eternal basis in fact. Such literature has not been with us very long, and there is nothing to indicate that it will continue with us for very long (at least the way it is going). If people don’t read it, it just isn’t going to be literature.”

Earlier in the introduction, Steinbeck told us he’d been “out of touch with my little world for a matter of three weeks” at the time Capp finally relented and got Li’l Abner hitched. The author, with his sons, Thom and John, was on Nantucket for spring vacation while Elaine Steinbeck was in Texas for her annual visit to her family.

“When I finally came to a stop so that mail could reach me, I found about thirty letters. [. . .] And practically every one of those letters began — ‘Have you heard that Daisy Mae and Li’l Abner are married?’ It was the most important thing that had happened in America. Well, that seems to me to prove that Capp is literature [. . .] Dogpatch is a very real place to us.”

“The World of Li’l Abner,” with its Steinbeckian introduction, is soon to be donated to Sag Harbor’s John Jermain Memorial Library. It seems the right place for it.