To Save a Barn

To Save a Barn

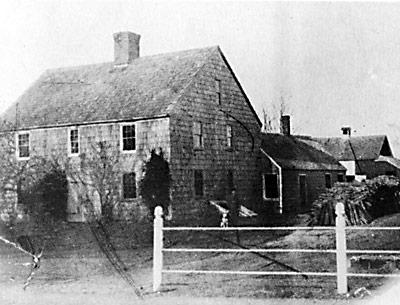

It may have been a hay barn at one time, but Tracy and David Gavant and their daughters call it the “happy house.” The Amagansett building, just off Main Street, dates to the early 19th century, but with expansion and some updating, it feels quirky, but modern.

Ms. Gavant said she and her husband fell in love with the house in 1999 at first sight. “We had been coming out here since we started dating, first in house shares, then graduating to couple shares. The house was available for rent or sale, and we looked at it for a rental but then realized we had to have it.”

CLICK TO SEE MORE PHOTOS

___

Ms. Gavant had been the publisher of Elle Decor and is now chief marketing officer for Interiors magazine. Given her background, “the last thing we were interested in was anything cookie-cutter or catalogue,” she said. The house, with its different rooflines and haphazard additions over the years, fit the bill.

Mr. Gavant was attracted to the house’s history. It was he who dated parts of it to the early 1800s. The surrounding land was once the Conklin farm and dairy. The original part of the Gavants’ house, the hay barn, is now the main hallway. The dairy barn has been moved to another part of Amagansett.

Legend has it that peonies around the property were offshoots of plants brought back by a Conklin ancestor, a sea captain who sailed to the Far East in the 19th century.

The Conklin family, who lived in a larger house on Main Street, which dates to the 17th century, used the small building out back as their summer house. This may have been because they were running out of room or, what is more likely, because they rented their house to city folks in the summer, a common local practice. In any case, the small house grew organically. “Whenever they needed more room they converted more to living space. Then, they would add more rooms to the house,” Mr. Gavant said.

When the Gavants first bought it, the house was cozy, perfect for a couple, if not necessarily for guests, who had to traipse through the living quarters to get to the guest bathroom off the kitchen.

Even so, the Gavants found the low doorways and eccentric layout charming — that is, until they had children. By then, the Thermidor industrial oven that came with the house, which had one side exposed, was becoming an uncomfortable hazard. It was hot to the touch and heated the house too much for comfort on a summer’s night.

Thinking about a kitchen redo, the couple consulted the architect Erica Broberg and her husband, Scott Smith of Smith River Kitchens. Ms. Broberg offered further suggestions that intrigued them. “The first thought was to replace the stove, which led to renovate the kitchen, which led to create two kids rooms, which led to renovate an old bathroom. It’s the ‘while we’re at it’ renovation,” Ms. Broberg said.

“We decided to keep with the ‘cottage scale’ and add a series of rooms,” Ms. Broberg said. The new rooms include a master suite, office, and kitchen addition on the first floor and bedrooms for the couple’s daughters, now 6 and 11, on the upper floor, with a reading nook and playroom. The former master bedroom is now the guest room.

Ms. Gavant said the reading nook was her favorite part of the house. Set into the upstairs landing over the kitchen with a built-in daybed and shelving, it was inspired by one at the Sunset Beach hotel and restaurant on Shelter Island.

The additions were to tie into the complex series of roofs on the original structure. But once Robert Biondo, the project’s contractor, who specializes in old houses, opened up the walls and beams, he found it “significantly under-supported and dangerous,” according to Ms. Broberg.

“We found old shutters used as subflooring and chicken wire within the walls. Those working on the site started calling the house ‘the chicken coop,’ ” Ms. Broberg said.

For Mr. Gavant, the work took on the character of an archaeological dig. “Everything seemed to have seven different layers.” Whether it was the exterior shingles, which were simply added on top of earlier ones over the years, or the different levels of carpet, wood, and linoleum on the kitchen floor, the house certainly had a history. The renovation revealed the barn’s original red-painted shingles as well as doors and wood co-opted from boats.

In the master bedroom, Mr. Biondo’s crew bent wood to form a gothic arch to mimic an existing one in the main hall. New floorboards had to be installed in parts of the house, but they were given a dark stain, consistent with the wide boards of an earlier time.

The kitchen has up-to-date appliances now and a drinks area, a second sink below an outside view, a corner fireplace, a butcher block island with a kids refrigerator built into it, and a wine refrigerator. The house now also has three porches, a front porch for after-dinner relaxing, a porch off the kitchen for outdoor meals, and a covered porch with a swing where the children play.

A second fireplace straddles the kitchen and living area. When she’s in the kitchen, Ms. Gavant said she likes to watch her two girls on the couch in the great room “hopefully reading, but probably watching TV, with my husband on the computer. With the fire going we get to share in the warmth of it all.”

The couple had discussed the renovation with a number of contractors, who told them to tear down the house and start from scratch, Mr. Gavant said. “Renovating the original structure would be more complicated and more expensive, but we said we didn’t want new construction. That’s not why we’re here.”

Mr. and Ms. Gavant praised the architect and contractor for managing to erase the transitions between this century and previous ones. “Their main goal was that people would walk in and not be able to figure out where the new construction began and the old house ended,” Mr. Gavant said, noting that most guesses are wrong. With merging rooflines and old-meets-new angles, Mr. Gavant noted “there’s not a straight line in the house.”

The furniture is subdued and the color palette neutral and bright. The Gavants personalized the space with flea market and tag sale finds, including bottles, books, and a huge collection of rubber ducks.

There is a calm that overtakes the family when they enter the door, Ms. Gavant said. “We will sit and do a puzzle at the dining room table as a family,” she said. The couple love to travel and are prone to cabin fever, “but I never feel that way here. There’s so much light and the peaceful surroundings are so much more conducive to relaxation. I want to stay home.”