HABITAT: Re-Imagined With Style

HABITAT: Re-Imagined With Style

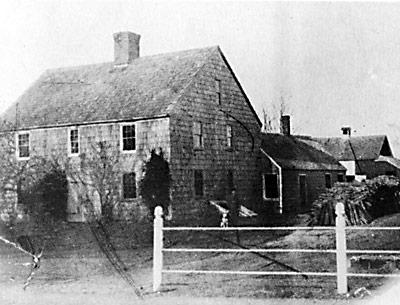

It may come as a surprise that a Dutch colonial house built in 1920 would epitomize an Italian minimalist style. But, after modest renovations, that is just how one would describe a Bridgehampton house today.

East of the Bridgehampton School, between the Montauk Highway and fields farmed by the McCoy family, the property also has a barn and several outbuildings, including a guest house.

Click to See More Photos

Fulvio Massi, an artist from Milan, and his wife, Naimy Hackett, who grew up in East Hampton, bought the property in 2008 from the estate of the renowned painter Esteban Vicente, who, with his wife, Harriet, had owned it for about 40 years. The house is said to have been built on the footprint of an 1850s house that burned down.

Mr. Massi, an architect as well as a painter, and Ms. Hackett, who writes English lyrics for pop songs produced in Italy and has taught playwriting at the Bridgehampton School, moved to the States in 2000 after living in Italy for some 30 years.

“The thing that we fell in love with,” Ms. Hackett said recently of the house, “was that it has such good bones and structure. It is a beautifully made, sturdy house.”

As it was once for Esteban Vicente, the barn is now Mr. Massi’s studio. It has an attached storage shed, and there are a tiny potting shed and a tool shed on the grounds in addition to the guest house, which has its own small kitchen area as well as a patio.

Of 2,000 square feet and with four bedrooms, the house itself had enough space for the couple to work with. At the rear, or south side, a small office became a sun-filled breakfast room with a view of the barn and fields. A tiny bathroom was moved near the kitchen pantry, and, coveting more interior space, the couple moved the entrance to the basement from inside to outside.

The breakfast room, which abuts the kitchen and living room, now has French doors, and there are two sets in the living room. The breakfast room is the only part of the house where flooring was replaced, using Douglas fir to match the rest of the floors. The chairs here and in some of the bedrooms are by Arne Jacobsen.

The kitchen, where the couple spend most of their time, restates the black-and-white, organic theme they adopted in other places they’ve lived. They installed black granite countertops and a black granite-topped work island, and replaced small, high windows with larger ones that are double-hung. Behind the counters, the backsplash is of quilted stainless steel, which, Ms. Hackett said, was inspired by some of the mobile food vendors in New York City.

The dining room’s black Le Corbusier table was brought from Milan, and the chairs around the table are by Bellini, a Milanese designer. A two-foot-long “Queen Titania” lighting fixture over the table, which some say is reminiscent of a flying saucer, was designed by Paolo Rizzatto and Alberto Meda. At night, the intensity and the color of the light it emits can be adjusted. The fixture, from Luceplan, comes in 5 and 10-foot lengths as well.

Sculptural sconces by Tobia Scarpa hang in several places in the house, including the second-floor hallway, which produce, Mr. Massi said, a lovely, sensual light.

In the living room, to the right of the entryway, an orange sofa by Piero Lissoni faces the fireplace. Two Eames chairs, a Le Corbusier love seat (“LC2 Petit Loveseat”) and two black, metal-rod-backed chairs (“LC2 Petit Arm Chairs), also by Le Corbusier, came from Milan as well.

Mr. Massi and Josh Dayton, a friend, built narrow bookcases on either side of two smallish windows in the living room, a window seat, and the fireplace moulding and mantelpiece. They replaced the trim and Mr. Massi added a crisp line to the existing door and window casings. He and Ms. Hackett built a coffee table, which sits in front of the fireplace, using wooden containers they found in the basement.

Mr. Massi also built all the beds, including one in the guest house, where the couple lived while the renovations were under way. The beds in the rooms that the couple’s two adult daughters use when they visit were made of cedar; the master bedroom bed is of stained poplar. The master bathroom has slate tiles, two marble basins, and a drawing of naked women dancing about by the Springs artist Ralph Carpentier, who gave it to the couple as a housewarming present. Mr. Massi added a round window to the bathroom, which looks out over a Concord grape arbor, the barn, and the fields.

Most of the paintings in the house are by Mr. Massi, who has been showing his work for about six years. An artist’s proof over the master bed is by Adolph Gottlieb, a founder of the New York Abstract Expressionist School, who lived in East Hampton and was a friend of Ms. Hackett’s parents, Walter and Vivian Hackett. A large painting on the wall next to the stairway is “Messy Diary” by Emanuele Diliberto, a Sicilian.

And the couple have other projects in the works. One is to put up a small, glassed-in area outside the Dutch door at the front of the house, to use as a mudroom. They also plan to turn one of the bedrooms, which Ms. Hackett now uses as a study, into a walk-in closet and to transform the 500-square-foot attic into her own aerie.

“We’re so in love with this house,” Ms. Hackett said. “It’s the perfect size. It’s not too big, but if you want to have guests, there’s room.”