The Art of Living Together

Living together is an art, not a mere scientific or mechanical adjustment. All the mechanizations of all the social engineers will not help a heterogeneous people to live together in brotherly, peaceable, happy relationship unless the individuals of society begin early, practice diligently, and learn to delight in the art of living with other peoples and different races.

In the United States we have the representatives of all races, but the major distinction in thought, and often in practice, is made between the vast “black” race and the vaster “white” race. This distinction is not biological; it is sociological and historical.

If the problem lay in biology, it would be hopeless for us, for it could be solved only by evolution, and evolution may take a million million years. In sociology we may take relatively short cuts through education, acquaintanceship, cooperation, social reaction. This is simple, but it is difficult, for we are hindered by habits, prejudices, selfish interests, and fear — and the worst of these is fear.

We need first acquaintanceship. People do not get acquainted through caste relationships. The master does not know the slave. The boss does not know the laborer; the employer does not know the employee as a man and fellow-citizen. The relationship of “inferior” and “superior” stands in the way of fraternal acquaintanceship.

Whenever two groups are handicapped by caste-customs, the stronger and advantaged group can never understand the weaker and disadvantaged group as well as the weak understand the strong. This is not due to any superior virtue in the weak but is due to their necessity: The weak must understand the strong; it is a condition of the survival of the weak.

Let us take Georgia for an example: Cultured, intelligent, and refined white homes in Georgia will be well known to colored people, but the homes of the poor whites, the uncultured and disorderly, will be unknown to colored people. Now let us get at the other end of this social telescope and take a look and everything will be just reversed. The better, the more cultured, and the more orderly a black man’s home is in Georgia, the surer we can be that no white man ever entered it. But the low, uncultured, disorderly homes of black people in Georgia are almost certain to be well known to white people, and to very influential white people: the sheriff, the chief of police, the prosecutor, the judge, the jury, and the readers of all the newspapers.

Neither race is to be blamed for this abnormality — it is nobody’s deliberate planning — it is in the very nature of segregated relationships. In such relationships the strong will control the weak and will therefore deal chiefly, almost exclusively, with the undesirable qualities and elements of the weak, while the weaker and poorer people will serve the strong and will therefore develop contacts with the economically better off and generally more cultured and refined sections of the strong.

But while we cannot be blamed for the inevitable results of a given system, we are to be blamed if we do not seek to alter the system and thereby secure better results. A dominant race will have an almost 100-percent knowledge of the crime and criminals of a subject race, because the dominant race will run all the courts and jails; but the dominant race may have an almost zero knowledge of the law-abiding persons in the weaker group, but that the others just have not been caught yet.

This is the only possible apology for the ridiculous statement of impatient and exasperated whites, who have dealt only with Negro thieves, when they say heatedly that there are no honest Negroes; when they have dealt only with ignorant blacks, that there are no intelligent Negroes; when they have had relations only with black prostitutes, that there are no colored women who are virtuous and chaste. If color-caste is capable of such vitiation of human relations, color-caste ought to be destroyed, and men of the same cultural levels ought to be recognized as men and granted the privileges of their culture.

In analyzing the art of living together, it is well to know that a human will like people better when he does something for them and hate them most when he does most against them. It is not the sentiment that causes the deed, it is the deed that causes the sentiment. If we want to like people, let us start doing good to them; if we wish to give nourishment to our hatred, let us feed it with deeds of ill against the objects of the hatred. Hate, in and by itself, is an empty illusion that would tend to vanish; to be kept in the semblance of life, it must be continually fed on the substance of deeds.

Let us see: There are two men in Illinois who are equally indifferent to Negro education, but being solicited, the one gives a thousand dollars toward Negro education and the other gives nothing. Subsequently let both of these men hear the same violent attack on Negro education. The one who gave will feel outraged by such an attack: “Negro education is all right, otherwise I would never have been such a fool as to give my money toward it.” While the one who refused to give will feel justified: “Good! I knew it was not stinginess and the lack of generosity that caused me to refuse to give, it was my good sense about the problem.” So much for the man who refuses to do good.

That explains why those who have for over two generations supported Negro education in America are practically 100-percent defenders of that cause, while some who have opposed it have become more desperate and violent in their opposition and will not acknowledge even when they are convinced. The man who fights a good cause must continually show that the cause was wrong in order to show that he is right.

White people have often marveled at the phenomenon that the American Negro, enslaved and oppressed, has not quite developed the hatred against his oppressors that some of his oppressors have developed against him. This has been erroneously set down as a contrast in racial traits, but it is simply the differences in spiritual need as between the perpetrator and the victim of a wrong. The one who is so unfortunate as to do a wrong has a far greater motive for developing hatred than has the unfortunate to whom that wrong is done; namely, the motive of self-justification.

Evidently, the more cooperation, the better understanding, and the better understanding, the better for living together. Cooperation brings acquaintanceship, and there is no substitute for acquaintanceship. No church creed, no bill of rights, no constitutional article, no wordy resolutions, and no pious prayers can ever be substituted for plain, old-fashioned acquaintanceship in the business of living together.

Segregation prevents or handicaps acquaintanceship. Therefore, no form of interracial segregation that it is practicable to avoid in a given community should ever be tolerated. An evil should not be allowed to spread; like slavery, race discrimination should be confined to its present boundaries and limitations until it can be destroyed.

Infinite patience is needed; sheer force can achieve little. In the present moment force cannot open the public schools of Georgia to colored children, but wisdom and foresight can prevent the closing of the public schools of New York to the children of any race.

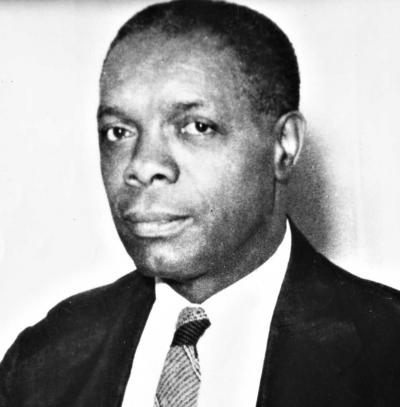

This is an excerpt from a 1934 speech written in hopes of improving race relations in America. William Pickens was a member of the committee that founded the N.A.A.C.P. in 1909 and a Phi Beta Kappa, summa cum laude graduate of Yale University in 1904. Bill Pickens of Sag Harbor is his grandson.