The Bad Old Days

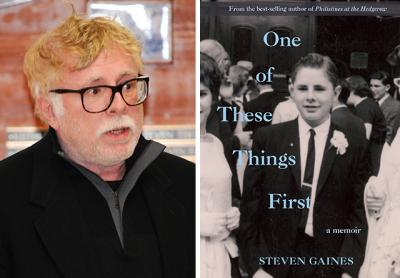

“One of These

Things First”

Steven Gaines

Delphinium, $24.95

A brief bit of history as prologue: The pathologizing of homosexuality is one of the great shames of psychiatry (and all other mental health professions). In 1952, with the publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-I, “homosexuality” was officially and disgracefully classified as a “sociopathic personality disturbance.” It was not until 1973, more than 20 years later, that the American Psychiatric Association finally removed homosexuality from its official DSM-II and started to treat it as other than a mental disorder.

Steven Gaines is the author of several books, including the 1998 best-selling “Philistines at the Hedgerow: Passion and Property in the Hamptons.” “One of These Things First” is his memoir. He was born in Brooklyn in 1947 and grew up there. Suffice it to say that in the 1950s and ’60s Brooklyn was not a wonderful place to grow up gay. I very much doubt that 50-some years ago there was a terrific place to grow up gay, but Brooklyn sounds, from his memoir, like a particularly challenging one.

It was unbearable enough that just a few pages into the memoir, when Steven is 15, he decides to end his life, and not in the take-some-sleeping-pills-and-slip-gently-into-a-sweet-oblivion kind of way.

I stepped back and considered myself in the mirror. No strapping high school freshman here. I was pale and pudgy, and I had tortured my mess of wavy strawberry blond hair into a perfect inch-high pompadour, hardened in place with thick white hair cream, like plaster of Paris. I had meticulously doctored an inflamed whitehead under my bottom lip with Clearasil, so I wouldn’t be embarrassed when they found me. . . .

Like a conductor about to give the orchestra a downbeat, I raised my clenched fists and then with all my might I punched through the two lower windowpanes of glass, one fist though each, one fist, two fists, except I ruined it because I had to punch the left one twice to get my fist through it. I sawed my wrists and forearms twice back and forth across the shards that held in the frame.

“The fairy is dying,” Steven thinks as he fades on the ground, predicting what Arnie and Irv, owners of a local luncheonette and two of his many tormentors, will undoubtedly think when they hear of his suicide. The police take him to Brooklyn Doctors Hospital. The doctor gives him a sedative injection and “whoosh I was numb all over. I vomited, probably wonton soup from the Great World that I had chosen as my last meal. . . .” And then he feels himself slipping into unconsciousness, “and the bus came by and I jumped on it just as graceful as Gene Kelly hopping on a trolley.”

Despite the grimness and gravity of the beginning of his memoir, Mr. Gaines employs an ironic and droll tone in viewing and portraying himself and his supporting cast of characters. There is zero self-pity here. No despondence or moping. The young Steven must certainly have felt sorry for himself from time to time and unquestionably was unhappy enough to try to take his life, but Mr. Gaines, the adult memoirist, is unfailingly bright, chipper, funny, and candid.

Mr. Gaines is a wonderful writer. His prose is crisp, informative, often lovely. He is always unflinchingly direct and honest about himself and those around him. He tends to think in film, by which I mean that he peppers his narrative with abundant references to the films of his youth. This is due no doubt to his grandmother having been chums with Murray, the manager of the Culver Theater, who always let him in without paying. “I went to the movies like other kids turned on the TV set.”

Because he feels different from nearly everyone he knows, the young Steven often observes his family and his neighborhood from afar, as an outsider. He regularly goes up to the El station on 18th Avenue.

“It was like a crane shot in a movie where the camera pulls back, revealing an Edward Hopper tableau come to life. I stood on the station platform transfixed for hours watching our little drama unfold below, the people going about their business, the big store [belonging to his grandparents] in the middle of the block with the pink neon Rose’s Bras Girdles Sportswear sign, the salesgirls and customers and shopkeepers, my father’s frightening rages, the tragic secret of my perversion, my grandfather’s shameful affairs, all this marked in quarter tones by the roar of the passing trains.”

As a young boy Steven is isolated by his sexuality and feels like a “freak,” “nature’s mistake”: “They always hated me at Hebrew school, where like a wolf pack they smelled out my homosexuality and expelled me as a weak pup.”

He hears his parents and their friends talking about Christine Jorgensen (an early trans woman who had been a World War II G.I.), “a homo who went to Sweden and had his dick and balls cut off. . . . I didn’t want to have my dick and balls cut off. So I kept it a secret that I was a homo as best I could. . . .” Michael, the only other neighborhood “homo” he knows, he thinks of as a monster in a science fiction movie “where a man melds with a woman, a creature that didn’t deserve to live.” But he figures that Michael knows about him because all of “nature’s mistakes recognize each other.”

A discordant but delightfully effective mix of desperate self-loathing and humor runs throughout the memoir. After his suicide attempt, Steven is asked why by his father and Dr. Doris, an adolescent psychiatrist (who, because she sits stiffly in a wheelchair, reminds him of Dr. Strangelove). “I did it because I’m the Frankenstein monster.” They decide to commit him to Hillside Hospital in Queens for long-term care.

When Steven realizes that Hillside is the dreary and awful facility with bars on the windows he can see from the Long Island Expressway, he is motivated to finish what he started. “Later that night I would slip out of the house and throw myself under the D train, northbound to Manhattan, which I thought was more glamorous than throwing myself under a train headed to Coney Island.”

But upon consideration that this strategy might prove difficult and painful, he remembers being warned about a man who peed on the third rail. Supposedly the electricity traveled up his urine stream into his penis, killing him. “I could pee myself to death; that would give them something to talk about.” Though funny, the idea of killing himself through the very piece of his anatomy that is causing him such angst is fitting.

Eventually Steven talks Gog, his wealthy grandfather, into paying for him to stay at the famed and fashionable Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic on the Upper East Side. It is a place where movie stars and famous writers stay for their “nervous breakdowns.” And it is here where, oddly enough, he meets people who share his sensibilities. They are wealthy, educated, well dressed, and artsy. And they are all unusual. Peculiar. Quirky. “She owned a small savings and loan in Vermont and shoplifted at Bergdorf Goodman.”

Steven is the ugly duckling who at last lands among swans. Here he finally feels at home, an atypical boy among atypical people, and here he also meets the man who would become his analyst for many years, Dr. Wayne Myers.

Even if it was a horrible thing to be a homo, it made me unique. That horrible part of me also made me special. . . . My curse in some ways made me . . . superior.

Dr. Myers watched my expression as this train of thought played out in my head. Special. Different. Something I’d chew on for a long while. He had managed to pull off a clever psychological sleight of hand by producing epiphanies out of a hat. Self-examination with a good shrink is like an opiate.

During the course of one of these talks, Steven tells Myers that he saw the film “Splendor in the Grass” 11 times.

He interrupted me, breaking protocol. “She [Natalie Wood] had a nervous breakdown because she wanted to have sex with her boyfriend, but sex is forbidden because she’s a ‘good girl,’ and her mother wants her to be a virgin. And her bottled up desire eventually drives her to a suicide attempt.”

I felt my cheeks go on fire.

Eventually Steven admits to his sexuality. “ ‘I hate myself,’ I whispered. ‘I’d rather die than be one.’ ‘I see,’ he said. ‘Is that why you tried to kill yourself?’ ”

This is the beginning of self-acceptance for Steven, though, this being 1962, Myers tells him, “Homosexuality can be cured, like many other disorders.” (As a psychoanalyst, this part made me cringe in shame and anger.) Despite this misguided bit of psychotherapeutic idiocy, Myers proves to be a pretty good analyst, and when Steven has a session with him decades later, Myers even apologizes: “I’m sorry I tried to change you. I’m afraid that, in retrospect, I caused you more pain.”

Thankfully, homosexuality is no longer thought of as a mental disorder, so that at least the teens of this generation will not grow up thinking of themselves as sick or freaks and can accept themselves more easily.

Michael Z. Jody is a psychoanalyst and couples counselor with offices in Amagansett and New York City.

Steven Gaines lives in Wainscott.