The Barrier Beach Blues

“Fire Island: Past, Present,

and Future”

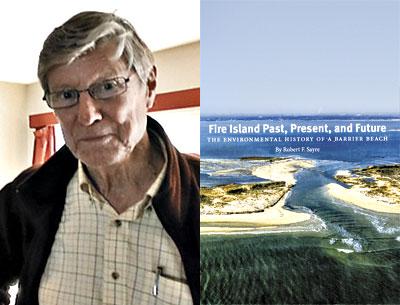

Robert F. Sayre

Oystercatcher Books, $24.95

Robert F. Sayre, a retired English professor from Iowa, had the pleasure of spending his summers from childhood onward at the family house in Point O’ Woods on Fire Island. From this long-term, personal experience, he gained a valuable perspective about this roadless island that is accessed by pedestrian ferry boats from the mainland of Long Island.

I must confess to being jealous of Mr. Sayre, as I grew up too far from the water’s edge and only migrated to the coast in later years as a coastal geomorphologist. I have had the privilege of conducting scientific studies along the South Shore of Long Island since 1977, with my most recent work being in the Hamptons. I devoted six years of my life to intensive studies of the area from Fire Island Inlet to Montauk Point, which culminated in the production of historical shoreline change maps that quantitatively display five or more shore positions during the past 100 years as well as a 350-page National Park Service monograph, “Geomorphic Analysis of the South Shore of Long Island, New York.”

I know the area well, having lived at National Park Service quarters at Watch Hill and the lighthouse in Kismet while conducting beach surveys of off-road vehicle impacts and driving vibracores through the sedimentary layers of the barrier island to determine its past changes.

The front cover of the book shows a new inlet cut by Superstorm Sandy through the eastern section of Fire Island, which has persisted to date. This wilderness area within Fire Island National Seashore is called Old Inlet because of previous inlet breaching in this same locality. Superstorm Sandy certainly heightened the interest of people “living on the edge” as well as mainlanders who fear this new inlet will increase storm tides during future hurricanes. The National Seashore has been under pressure to close the inlet, as was the case for the other two cuts, but wilderness areas are special places (e.g., this is the only one in the State of New York) where nature can take its own course without interference from humankind.

This slender, oblong book is organized chronologically, with many color and historical black-and-white photos that serve well to illustrate the text. I applaud the author for taking his posters and converting them into such a handsome booklet.

Most people will enjoy reading this book, but there are many mistakes from the perspective of a coastal scientist, starting with the caption for the frontispiece, where overwash deposits are attributed to Hurricane Sandy. Sandy was not a hurricane on Long Island, as the sustained winds reached only 50 to 60 miles per hour (i.e., far short of the required 74 m.p.h. wind field), and it was responsible for a snowstorm in the Appalachian Mountains — hardly the hallmark of a hurricane.

Second, there needs to be a map as the first figure with sufficient detail to show the 17 communities on Fire Island as well as other island features. What is finally presented on page 60 is a reproduction and reduction in scale of the National Park Service brochure, making nearly everything illegible without a magnifying glass — something that few take to the beach or carry on airplanes.

Many of the photos are from Point O’ Woods, which is understandable, but the iconic Fire Island Lighthouse is only briefly mentioned, and one small photo of it is presented on the last page in the reference section. This sentinel was constructed near the western terminus of the island in 1825, and since that time, the island has built westward by longshore currents at the astonishing rate of around 150 feet per year. It was only the construction of the Democrat Point jetty and regular dredging of Fire Island Inlet to keep it navigable that have prevented this downdrift growth of the island as a sand spit.

In fact, the whole barrier chain along the South Shore of Long Island was doubtless formed over thousands of years as a sand spit emanating from the morainal cliffs in East Hampton. Historical studies have shown that the Montauk Point Lighthouse was constructed more than 200 feet from the cliff edge. The surveyor in charge was George Washington — he wanted to make sure that the lighthouse lasted for several centuries. Our first president and brilliant general during the Revolutionary War was also an astute observer of coastal change.

Throughout this book there are statements such as armoring the bay shore with bulkheads “tends to increase erosion at other points” along the barrier island. Although localized erosion can occur, there is no generalized increase in bayside erosion rates. The real problem with wooden bulkheads is the poisons used to preserve the wood that leach out and contaminate the adjacent bay bottom. In addition, bulkheads form a sterile interface, rather than the highly productive environment of a salt marsh.

On page 67, the author repeats a long-disproven theory that the Westhampton Beach groins and Moriches Inlet jetty are responsible for erosion problems on the western end of Fire Island, where the 17 communities are located. The Fire Island Association has been lobbying for decades to make the federal government responsible for their erosion problems so that they can obtain beach nourishment via the Army Corps of Engineers at 100-percent public expense. While it would have been far cheaper for the federal government to buy out the few hundred residents in the area now known as the Village of Westhampton Dunes rather than guarantee them a wide and stable beach for 50 years, there was no denying that the updrift (eastward location of the 15 long federal groins) had greatly accelerated the erosion rate, causing severe losses during the 1992 northeaster. The same case cannot be made for the 17 communities on Fire Island. (My colleague Francis Galgano and I wrote about this in “Beach Erosion, Tidal Inlets, and Politics: The Fire Island Story,” an article in a 1999 issue of the journal Shore and Beach.)

The Fire Island Association also played a key role in re-electing U.S. Senator Alfonse D’Amato in his very tight race in 1992. Known as the “pothole” senator for bringing the money home to Long Island, he paid back the Fire Island Association for its raising millions of dollars in the final days of this close election — he stopped a Senate vote on a bill, already passed by the House of Representatives, to mandate that the Federal Emergency Management Agency could use erosion rates in their National Flood Insurance Program.

I certainly agree with the author that deer are a major problem on Fire Island. In addition to impacting the natural environment by eating native plants and exposing the sandy, mobile substrate, they are responsible for Lyme disease, which is a serious illness. The National Park Service should eliminate every deer on the island for the sake of the natural environment because there are no natural predators and deer overpopulation is a continuing problem. During especially cold winters as just experienced, Great South Bay can freeze solid, and the deer can walk from the mainland to the island, but these newcomers can be quickly weeded out by experienced hunters using bows and arrows.

Over all, this book will probably have a good reception from the general public, especially Fire Island residents. To his credit, the author did consult some of the U.S. Geological Survey reports, but it appears that this occurred in the final stages of writing because the science is not well explained or referenced, whereas the history, especially for Point O’Woods, is quite strong.

Stephen P. Leatherman, known as Dr. Beach, is the director of the Laboratory for Coastal Research at Florida International University and the author of “Dr. Beach’s Survival Guide,” among other books. In 2013 he ranked East Hampton’s Main Beach as the best in the nation in his popular annual top 10 list.

Robert F. Sayre, a descendant of one of the first settlers of the South Fork, is the author of “Thoreau and the American Indians” and the editor of “Recovering the Prairie” and “Take the Next Exit: New Views of the Iowa Landscape.”