Calling Papa Hemingway

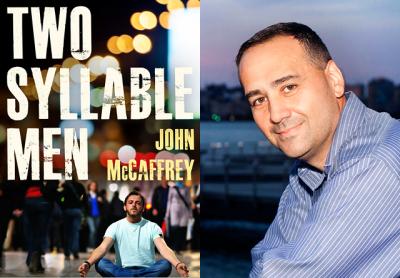

“Two Syllable Men”

John McCaffrey

Vine Leaves Press, $14.99

“Two Syllable Men” by John McCaffrey is a short collection of 12 stories in which the men are either a) divorced, b) in the process of getting divorced, c) looking for girlfriends, or d) dissatisfied with the girlfriends they have. And the women assume the roles of ex-wives, ingenues, manic pixie dream girls, or, in one memorable instance, a psychologist who eats barbecue pork sandwiches during therapy sessions.

The main thrust of the book is the existential search for pure masculinity — whatever that might mean in a time when the gender binary is rapidly decaying. Mr. McCaffrey manages to both subvert and reinforce the Bechdel test, which, to pass, a work of fiction must have at least two named female characters who talk to each other about something other than a man. In “Two Syllable Men,” the male characters exist in the stories only in relation to women. The bulk of their interactions are with women; the majority of their thoughts are about women. On the other hand, the women function as the objects of desire, or to facilitate the life-changing realizations of the men.

In “William,” the first story in the collection, William looks through his girlfriend’s notebook, and what she’s written there causes him to recall a fight when she accused him of cheating with “some young girl.” William called his girlfriend (she is not named) “crazy” and “possessive.” Something else she’s written reminds him of “the night before. They had gone to a movie. And then back to her apartment. They had undressed each other. Played. Danced and wrestled their way to the bedroom. Then, on her low-lying bed, they kissed. And he was flooded with joy; it ripped through him. He had gripped her bare shoulders. Licked at her skin, off-white and flawless. Gripped her tighter and tighter; absorbed her body. Later, as they lay sated, he looked at her and said: ‘I feel so content.’ ”

We do not know what the girlfriend makes of all of this — the dancing, the wrestling. She’s gone out to fetch pizza and, for the reader, lives only in William’s memories. The story is two pages long, but by the end it appears that William has resolved to be kinder in the relationship, more aware. “William walks toward her, searching for the right word.” It is the subtle use of the word “right” that indicates William has changed, and for the better.

The following stories, “Daniel,” “Graham,” “Kevin,” etc., center on damaged men (“a man without purpose or identity”; “I was hurting from my wife walking out on me”; “after his wife left him, Byron tried to blunt his loneliness with obsession”; “Steven felt inadequate in this raucous world of ribald men”; “after my wife and I separated, I spent most evenings wandering the cavernous aisles of a local Sam’s Club”) pursuing or being pursued by attractive women (“she was tall and stylish in a beige mini with matching heels”; “a great looking blonde in a halter top”; “a tall, lithe woman”; “the sound of her voice ignited an erection”; “she was wearing a black turtleneck that accentuated long, taut breasts”; “she was tall and shapely”).

All of these stories are variations on the classic boy-meets-girl scenario. Mr. McCaffrey has a knack for plotting, moving briskly between scenes in a way that holds the reader’s interest. Threaded throughout the book are references to “The Sun Also Rises,” most explicitly in “Thomas,” a meta-story wherein Thomas is cast as Cohn in a dramatized version of the novel. What convinces Thomas to take the part is the possibility that he might have a chance to sleep with the actress portraying Brett. “An image of Carolyn’s nipple popped into Thomas’s mind. Things started to seem less complicated. He visualized the two of them together. And then he gave his answer.”

Moments of humor like this add an absurdity to the world of “Two Syllable Men,” in which masculinity is ever at stake and the male characters feel as though they’re on the verge of being outed as phonies.

What “Two Syllable Men” aims to do, according to the copy on the back of the book, is “explore the male psyche in all its fragmented glory.” It’s an inward, navel-gazing collection of stories. The characters have a bluster, a bravado that’s often countered by a raw vulnerability. If they can just find the right woman, their problems will be solved.

The overall impression, after reading the book cover to cover, is that women are from Venus and, yep, men are still from Mars. This lends a melancholy feeling to the stories. The characters are separated from one another along gender lines. They want to connect, but they can’t quite figure out how to cross the divide.

Emily Smith Gilbert is the managing editor of The Southampton Review. She lives in East Hampton.

John McCaffrey is the author of “The Book of Ash,” a science-fiction novel. He lives part time in Wainscott.