The Dead Don’t Lie

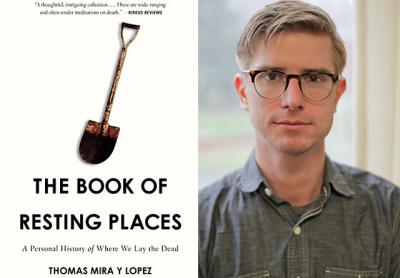

“The Book of Resting Places”

Thomas Mira y Lopez

Counterpoint, $26

I don’t know if “tour de force” can be applied to a 23-page essay on death — big subject, limited space — but Thomas Mira y Lopez packs so much, so subtly and so smoothly, into “Memory, Memorial” that a reader can be forgiven for wondering.

It opens his debut essay collection, “The Book of Resting Places,” as he visits the house in the Pennsylvania countryside where his mother has been left to figure out what comes next after what gave her life meaning is gone. At the center of the visit is the Ohio buckeye tree, now more than 20 feet tall, that her husband, Rafael, a cell biologist, had planted before a seizure led to two craniectomies and paralysis. The tree, visible from the kitchen window, becomes a stand-in for the father, as does an American elm in Central Park, purchased as a memorial tribute, which takes a dark turn as the author contemplates the number of branches in the park that have fallen and killed people.

Mr. Mira y Lopez reveals himself to be something of a scholar of classical mythology, here the seed of a tree becoming a metaphor for a coin to pay Charon for passage across the underworld rivers Styx or Acheron. Later, we see him wedge a coin between his father’s dead fingers. “He might need this,” he tells his mother.

Part of what’s appealing about this author and guide is how hard he is on himself. It shows honesty. As when he goes on to explain that what he’s really doing is setting his father afloat like driftwood on the Lethe, the river of oblivion and forgetfulness, “trying to obscure memory, to make surreal or unreal what I would otherwise have to account for as the truth.”

He pulls the old trick of imagining he’s standing outside himself, watching his motions as if he were part of a movie, as he runs through Central Park and his father lies dying. Later in the vigil, he says to himself, in essence, Where’s the harm in taking a break to catch the Giants game and order Chinese?

The answer comes in a bracing turn as his father, in an expletive-laced harangue from the grave, excoriates his son for his inattention: “. . . you tried to pretend I wasn’t there . . . you stayed away while I was dying . . . you were content to let me go if it made your life easier, you selfish son of a bitch. But now I’m coming to get you.”

He haunts the rest of the book.

Meanwhile, the mother, Judy Thomas, is no cipher, no mere figure of sympathy, not simply some eccentric widow, although she does imagine herself entombed in her afterlife by mounds of her own belongings in an 8-by-10 Manhattan Mini Storage cube, climate-controlled behind a corrugated steel door, her cremains settled in next to Senator Sumner’s desk and a painting by Alfonso Ossorio.

In fairness, her first wish was to have her ashes placed in a low stone wall next to her parents’ behind St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in East Hampton (the author spent a good chunk of time hereabouts as a kid). Decades later, she still laments the tomb-raiding actions of her own relatives, “who took all the best stuff” from her mother when she left East Hampton, stealing away, in her son’s words, “what kept the dead alive.” Her thinking, he adds, is that “if she recovers her mother’s prized possessions, she’ll recover her mother herself.”

Possessions — kept, jettisoned, shown, stored — figure throughout the book, and in eye-opening ways, for instance in the definitions of a collector, who “displays a self,” and a hoarder, who “searches for one.”

Among the journalistic pieces, Mr. Mira y Lopez visits a real pro of a collector near Tucson, where he got his M.F.A. in writing. The collector, Roger, owns a junk shop chockablock with historical artifacts — a mummified 4,500-year-old child, the skull of a Mexican soldier shot at the Alamo — much of it insensitively displayed. Roger is friendly, engaging, entertaining; the author likes him a lot. But when he discovers Roger’s racist id revealed on Facebook, his reaction is dispassionate rather than visceral, and it ties in with one of the book’s themes — the bifurcation of the self. The old saw has it that we’re all different people every day. Here it’s posited that we’re different people at one time.

What’s more, if the person you care most about disappears, and you’re left bereft, clinging to memories, who exactly is the ghost?