Denatured and Denuded

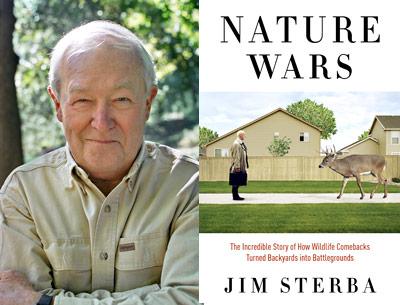

“Nature Wars”

Jim Sterba

Broadway Books, $14.95

Last September, deer became a deeply personal issue for me, and I crossed over to the other side, where I’d never been before.

I live in the woods of the North Fork along with an expanding family of deer that I wish I didn’t have to see every day. Ten years ago I would hold my breath and run for my camera on the family’s occasional visits, exulting over my relationship to nature. I felt privileged and honored by their presence.

More recently, forced to acknowledge that their eating preferences controlled my planting decisions, the exulting waned along with my gardening interests, and I justified my new laissez-faire shoulder shrugs by proclaiming that “they live here too; they were here before I arrived.”

After a standing-room-only Southold Town meeting in September during which a succession of local and other experts revealed the true extent of what was now being described as a plague, my deer beliefs underwent such transformation that I wondered whether my experience might rival Paul’s on the road to Damascus! I left the meeting utterly clear that only an immediate and radical culling of the thousands of deer in our town would do. To argue for anything less would be sentimental and irrational.

This clarity was established for me by the second speaker, a botanist, in his description of the deer’s destruction of the understory, the technical name for the forest floor. If the deer were killing my woods, I thought, they could no longer live here. They would have to go. Forests come first.

This speaker also introduced the audience to Jim Sterba’s book “Nature Wars: The Incredible Story of How Wildlife Comebacks Turned Backyards Into Battlegrounds,” essential reading, he said, if we were to understand the trajectory that had brought us to our current plight. That’s what makes this book so important: It lays bare the inevitability of our deer plague on the East End, demonstrating that it could not be otherwise.

Mr. Sterba, a veteran reporter for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, brings us a story that is indeed incredible. He tells it meticulously but gracefully, replete with numbers and facts so startling that at times I felt I was reading the back story for a dystopian movie! “Nature Wars,” a history and then a “new arrangement of man, beast, and tree,” analyzes the changes in the American landscape over the past 500 or so years.

Schoolchildren are taught about the arrival of Europeans in the 15th century and the impact of colonialism on the land’s native peoples, but less familiar perhaps is the resulting 350 years of extensive deforestation and brutal exploitation of wildlife that precipitated the conservation, rehabilitation, and renewal movements of the late 19th and 20th centuries. These attempts to reverse centuries of depletion led not only to the regeneration of forests and the renewal of wildlife, but also to what Mr. Sterba shows has become a dangerous overabundance, not least because of a “species partisanship” focused on saving the wolves or the cats or the trees without reference to the greater ecological system of which each is part.

This imbalance would not have happened without the postwar development of the automobile industry, interstate highways, and the migration of urban populations to the suburbs, to the sprawl between cities and farms, the “geography of nowhere” where, according to the 2000 census, the majority of Americans now live. Designed by humans for their own comfort, the sprawl territories have proved just as desirable for wildlife, providing them with not only food but also shelter and protection from predators. Wildlife, it turns out, likes what we like!

Mr. Sterba grew up on a farm in rural Michigan in the 1950s, learned how to kill, clean, and eat birds and animals, and enjoys hunting — and venison — today. From this perch, he laments the “denatured” people that today’s Americans have become, locked into climate-controlled houses, experiencing nature at a remove through car windows or as cartoons and staged documentaries on electronic screens. We now live what Mr. Sterba calls “a denatured life” where nature is feared or disliked and wild animals are perceived in unrealistic ways as “adorable pets” rather than the wild creatures they are until the time that they inhabit our habitat, proliferate, and end up demonized.

He traces our culture’s anthropomorphizing of wild animals to Walt Disney and “Bambi” in 1942 and, further, to the beginning of the 20th century, when writers such as Jack London and William J. Long “took liberties” writing their best sellers about the natural world and were dismissed as “nature fakers” by the conservationist President Theodore Roosevelt.

Here on the East End we are focused on deer, a parochial view if we look through Mr. Sterba’s expanded lens to this country’s overpopulations of wild geese, beavers, nutria, coyotes, wild turkeys, black bruins, and, yes, feral cats. The sheer numbers he cites are astounding: Hunters and other predators kill 12 million deer each fall, and 25,000 wild geese reside in the New York metro area. Sixty million to 90 million feral cats are said to kill 500 million birds each year in this country. Describing bird feeders as “wildlife aggregators” and characterizing highways as “wildlife magnets,” Mr. Sterba cites daily road-kill estimates of as many as a million birds and animals. (Road ecology has emerged as a new academic field to study the relationship between roads and the environment.)

These numbers encourage macabre reflection on abundance and challenge us to parse our prevailing notions of culling, wildlife management, and species and wilderness extinction. Mr. Sterba deepens the provocation by blaming our ills on the consequences of “too much of a good thing” rather than a “narrative of loss.” It’s the excesses of the rich man’s burden we carry, excess measured in terms of the car-wildlife collisions we have on interstate highways and then repair, our blithe discarding of edible deer meat and hides, the $50 billion we spend on pets, and the $5 billion to feed wild birds.

Recognizing we cannot easily undo what we have wrought and that changing our nature is not a trivial undertaking, Mr. Sterba avoids prescriptions while encouraging us to “understand and accept the need for human oversight” so we can ponder: How much of nature is in fact our business and how much should we leave alone? To what extent has our personal denaturing left us with a misplaced compassion that conflicts with stewardship of our complex ecosystems?

But be prepared when you read this bountiful book to question and rearrange your closely held beliefs. I did. I also discovered that the birds of my feather did not necessarily share my new fervor and that we may not so naturally flock together — at least for the moment. Be prepared for challenging encounters when you discuss your town’s deer management plans and what it means to feed wildlife and to have gardens, landscapes, mulch, composts, bird feeders, and cats. But first read this book!

Hazel Kahan lives in Mattituck, hosts two radio programs on WPKN, and writes about growing up in Pakistan. Her website is hazelkahan.com.

“Nature Wars” was recently released in paperback.