Drive, They Said

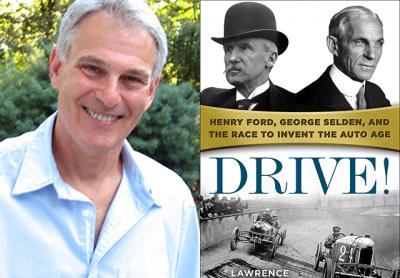

“Drive!”

Lawrence Goldstone

Ballantine, $28

Lawrence Goldstone has come down to earth. Following his 2014 book, “Birdmen,” a history of early aviation, he has now presented us with “Drive! Henry Ford, George Selden, and the Race to Invent the Auto Age.” (Dare we speculate that his next topic will be submarines?)

“Drive!” is a highly readable melding of business history and cultural history, focusing on a brief period of time, around the turn of the last century, when the advent of the automobile changed the American scene forever.

Although the emphasis is clearly on America — and ultimately on Henry Ford and the company he founded in 1903 — Mr. Goldstone enriches the study of his subject by including chapters on the scientific development of the internal-combustion engine, dating back to the 17th century, and on the development of the automobile in Europe, which began slightly earlier than it did in the United States.

The parallels on both sides of the Atlantic are striking. They include a great deal of trial and error. At first, the horseless carriage was assumed to be a frivolous fad that would soon pass. The invention was initially a plaything of the wealthy. The notion of speed, however, engaged the popular imagination. Automobile races, in Europe and in America, were immensely popular events, despite their tendency to produce gruesome injuries and fatalities among participants and spectators alike. The attention-grabbing Vanderbilt Cup race, underwritten in 1904 by William K. Vanderbilt II, a racing enthusiast, was originally to cover a course from Sag Harbor to Brooklyn.

“By June, Willie K. was finally resigned to the route he had chosen not being approved, so — reluctantly and with some irritation — he shortened the course to a 30-mile triangle, which would be traversed ten times. . . . The roads on the triangle were almost entirely within Nassau County, just east of the New York City line, but one corner spilled over into Queens. . . .”

The passion called “automobilism” swept across Europe and America, and it was not destined to be short-lived.

Though much about Henry Ford’s actual accomplishments is enshrouded in uncertainty — he is portrayed as perennially quick to take credit for things without acknowledging the contributions of others — it is indisputable that he was among the first Americans (possibly the very first) to see the widespread potential of the automobile across the wide swath of both urban and rural sections of the country. Thus, “while most of his competitors vied to make a more prestigious automobile, a more luxurious automobile, a more unique automobile, Henry Ford set about making an automobile that was plain, dull, and precisely the same as every other, right down to the color of the paint. But his car would also be supremely functional, simple to operate, and built not to impress but to get its passengers reliably from one place to another. . . .”

That is how Ford became the wealthiest man in America.

At the heart of Mr. Goldstone’s book (though I am not convinced that it is the best part of the story he has to tell) is an event that occupied newspaper headlines at the time but has been relegated to the footnotes of history books for probably a century now. In 1895, George B. Selden, a patent attorney from Rochester, obtained a United States patent on a gasoline-powered automobile, although he never produced a single working specimen of the invention. When others did begin to produce motorcars, in the early 1900s, Selden asserted his patent rights and demanded the payment of royalties.

Several leading manufacturers — including Winton, Cadillac, Locomobile, Peerless, and Olds, among others — acquiesced, paid royalties to Selden, and formed the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers. Others, including the staunch individualist Henry Ford, did not. And not just because they didn’t want to. Ford and others disputed the relevance of the Selden patent on substantive grounds.

While it lasted, the conflict was intense. Selden placed advertisements threatening not only unlicensed manufacturers with lawsuits for patent infringement, but threatening also their dealers and the purchasers of their vehicles. (Ford was quick to indemnify his dealers and all purchasers of Ford automobiles.) Mr. Goldstone’s description of the simultaneous automobile shows in New York in 1906 — one sponsored by Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers, the other by the competing Automobile Club of America — captures the ethos of the moment. “The dual — or dueling — auto shows were, to that point, the most significant public display of the rift among automakers.”

The Selden patent dispute amounted to a kind of American archetype playing out, pitting the inventor, the son of a prominent judge who was one of the founders of the Republican Party, against the plainspoken son of a farmer from Michigan. Ultimately, the matter went to trial. The decision was appealed. One can infer the outcome from the fact that George Selden’s name has been widely unknown until the publication of this volume.

While car buffs might revel in the plentiful detail provided by Mr. Goldstone, the greatest pleasure in this book is due to the colorful cast of characters, the amusing anecdotes, and what I can only describe as fun-to-know trivia. Consider the number of recognizable automobile names that receive first names here:

John and Horace Dodge (who worked with Ford until they left to begin their own auto company), Louis and Arthur Chevrolet, Ransom Olds, James Ward Packard, Armand Peugeot, Gottlieb Daimler, Karl Benz, Louis and Marcel Renault — we are well reminded that these were people (often quite interesting ones) before they were cars.

It makes sense that the automobile was originally marketed to doctors, as a time-saving (and thus a lifesaving) device. Personally, I was pleased to learn exactly how the name Mercedes-Benz was arrived at. And another longtime mystery was answered for me: Among my early childhood memories, in a Midwestern suburb, was that the family across the street, in the early 1950s, drove a Hudson. It’s the only one I ever saw or heard of. It seems that, in 1908, the Detroit department-store magnate Joseph L. Hudson (if you’re over a certain age, you will have heard of his emporium) bought a failing automobile manufacturer and began producing low-priced cars. “Never an immense success, Hudson was sufficiently profitable to remain in business until 1954.”

A last bit of good trivia: Ford’s first car was the Model A, in 1903. Each time changes were made or a new prototype developed (not all went into production), the letter changed. The Model T, the car that “made” the Ford Motor Company, was produced from 1909 until 1927. Counterintuitively, it was followed by another Model A, from 1927 until 1931.

Finally, Mr. Goldstone deserves credit for his handling of Henry Ford himself, a prickly subject, at best, for a historian to take on. The author’s treatment is balanced. He gives the automaker credit for his iconic accomplishments but does not shrink from describing his shortcomings. Ford was a misanthrope, a cruel player of practical jokes, and a terrible father (Mr. Goldstone’s contrasting descriptions of Henry and Edsel Ford, his only son, are particularly touching).

Even though the elder Ford was not the sort of person you would invite to your next party, there is no denying the significant place he occupies in the annals of American business.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader periodically contributes book reviews to The Star.

Lawrence Goldstone lives in Sagaponack.