Eastville Tintypes, From Floor to Wall

The Eastville Community Historical Society has a unique and rich story to tell about its background and earliest residents, one it can and will tell visually in the coming days.

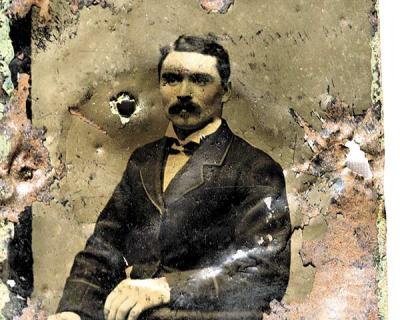

On July 11, it will open "Collective Identity: Portraits of Early Eastville Residents, 1882-1915," an exhibition of high-resolution reproductions of tintype and cabinet-card albumen images taken by William G. Howard, a 19th-century photographer who lived in the area and knew his subjects well. The result is a vivid document of a group of individuals whose personalities shine through the surface and who have a dignity and level of comfort unusual for any portraits of the time, but particularly those of minorities.

But just like Eastville’s mix of three ethnicities (African-American, Native American, and European immigrants), the images are also ethnically diverse. The subjects, all working class, range in age from babies to those late in life.

They have a formality and grace one would expect from portraits engraved on currency. Taken in Howard’s Sag Harbor studio, the subjects are mostly seated and in their Sunday-best attire. They are portraits that “show personality, dignity, and respect,” Donnamarie Barnes said recently. She is the photo consultant and conservator for the historical society and has managed the research, which has led to several identifications of sitters who had been previously unknown.

Georgette Grier-Key, the director of the historical society, added, “It’s unusual to see marginalized people of that era look so dignified and in clothing they had pride in wearing.” She said that she and Ms. Barnes feel a duty to them, both in their efforts to identify them and in their preservation. “Their spirits seem to say, ‘Don’t forget about us. Don’t let this history die.’ ” In addition to the exhibition, a book of the photographs with a history of them is in the offing. According to Ms. Grier-Key, it is the largest collection of African-American portraits and historical tintypes on Long Island.

The historical society has had the tintypes in its collection for years, but did not have the resources to address them in a scholarly way, nor display them without risk to their delicate condition. In the past year they had digital images taken and printed by Brian Luckey. Some came to them in photo albums found in a nearby house, but others were donated as a result of an unusual find.

Greg Therriault, who owned Ivy Cottage in the Eastville neighborhood until 1991, was renovating his house in 1978 when he came upon some metal tiles nailed to the floor in a back bedroom. When he lifted them up, he discovered 21 images, according to Ms. Grier-Key. She said it was part of the “quirkiness of the area, that such items might be used to keep out a draft,” adding that earlier East End residents were known for recycling timbers from old ships and moving entire houses to new sites with some regularity.

Because it was the back of the tintypes that faced up, the images, while degraded, survived. The backs have some green paint from an earlier attempt to match them to the floor color. Mr. Therriault collected them and gave them to the historical society soon after he discovered them.

What is a tintype? It is a positive image, such as you would get from a Polaroid camera — to give a more modern example — transferred directly to a thin piece of metal that has been lacquered or enameled. The treated surface is then used as the base for the photographic emulsion that allows the image to adhere to the surface.

While addressing the photographs was a priority of Ms. Grier-Key when she took the helm three years ago, her administrative responsibilities took up much of her time. It was the June 2014 retirement of Ms. Barnes, who had been a photo editor at magazines such as People and Life, that served as a catalyst to set the current project in motion.“We feel it was divine timing,” Ms. Grier-Key said of Ms. Barnes’s availability and her experience with photos, archives, and even genealogy, which has been key in identifying some of the unknown sitters. Eastville’s listings in the census records of the time have been very helpful.

Here is what they know about the photographer. Howard operated his Washington Street studio from 1882 to 1914. He was born and raised in Southold, and his father was an early photographer. He settled in Eastville in 1880 after hemarried. In addition to being a local businessman he was also chief of the Sag Harbor Fire Department for many years.

As for his subjects, they include the Green family, Esther J. and Henry Green, married in 1845, and some of their nine children, whose names were Charles, Mary, Sarah, Priscilla, Susan, Ida, Chinea, George, and Christina.

Mrs. Green was the sister of David Hempstead, who was a co-founder of St. David A.M.E. Zion Church. In 1840, the siblings were recorded as working at Sylvester Manor on Shelter Island as servants. She met her husband as a domestic in a New London, Conn., house. Mr. Green was born as a free man of color in New Jersey and was working as a boatman on Nantucket at the time.

They moved to Liberty Street in Sag Harbor after their marriage. They lost their eldest son to illness while he was fighting in the Civil War in 1864. Mr. Green had died the month before his son. Mary and Chinea died in childhood. Ida died after she was married. George, who was born in 1862, could not be found in the census after 1880.

Mrs. Green lived with many of her children in the Eastville house for the rest of her life. Four of the daughters never married and worked as seamstresses and domestics. Priscilla worked for a time in Providence, R.I., but returned to Sag Harbor and lived with her cousin Mary Hempstead in a house on Hempstead Street.

Nathan J. Cuffee, a Native American, was born to Jason James Cuffee, a Montaukett, and Louisa R. Cotton Cuffee, a Naragansett. He grew up on Liberty Street. His father was a whaler and laborer. He married Marie Louisa Payne, who immigrated from Barbados when she was 11. The couple eventually moved to Shelter Island, where he co-wrote a book with Lydia Jocelyn, who was married to a missionary from the Sioux Reservation in South Dakota. The book, “Lord of the Soil: A Romance of Indian Life Among Early English Settlers,” came out in 1905, making him the first published Native American from Long Island. Despite its title, the novel was full of conflicts and rivalries between the settlers and the different tribes of New England. He and his wife eventually moved to Islip, where he died in 1912.

The collection includes some tintypes and cabinet cards of European immigrants as well, but the historical society has not been able to identify them yet. “Our hope is as more people see the images and come to the exhibit someone will recognize them and tell us who they are,” Ms. Barnes said. One woman, whom Howard embellished with hand-painted rose-colored cheeks, fascinates her. “She just looks like she has a story.”

The show will be up through Oct. 10.