A Ghastly Record

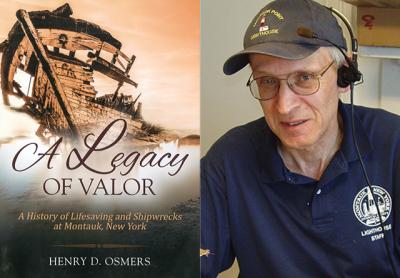

“A Legacy of Valor”

Henry Osmers

Outskirts Press, $23.95

In “A Legacy of Valor: A History of Lifesaving and Shipwrecks at Montauk,” Henry Osmers begins his fascinating narrative by describing a time when Montauk was almost void of European settlers. First House, Second House, Third House, and the Montauk Lighthouse were all that was there when the first lifesaving stations appeared in Montauk. He explains that, given the remoteness of the area and its lack of population, it was difficult to offer assistance to any ship that fell victim to storm, fog, or other maritime peril.

Mr. Osmers quotes an 1876 report that stated that “the Long Island and New Jersey coasts present the most ghastly record of disaster. . . . The broken skeletons of wrecked vessels with which the beaches are strewn . . . sorrowfully testify to the vastness of the sacrifice of life and property which these inexorable shores have claimed.”

It was these conditions, Mr. Osmers reports, that led the nation’s federal government to organize a growing network of lifesaving stations under the control of the Treasury Department. Mr. Osmers then offers a succinct account of the formation of the U.S. Life-Saving Service and its eventual arrival in Montauk. He also describes the two types of rescue strategies used by the lifesaving station crews. Rescues were attempted by boat or by a strong line that stretched from the shore to the troubled vessel.

Mr. Osmers details several different surfboats used in the rescues, various pieces of equipment used in them, and how the lifeline attempts were implemented. He also goes into the lives and activities of some of the men who served on the lifesaving crews.

After sharing accounts of the lifesaving stations at Montauk Point, Ditch Plain, and Hither Plain, Mr. Osmers offers descriptions of more than 100 shipwrecks that took place there over the past 300 years, divided by the time periods 1600s to 1877, 1878 to 1914, and 1915 to the 2000s.

Besides the straightforward listing, by date, of these wrecks, the author incorporates numerous accounts of witnesses to these tragedies. For example, in the aftermath of the wreck of the clipper ship John Milton in 1858, one witness wrote, “It was a sad, sad sight that our eyes were called to witness as all those stark and frozen bodies were brought and laid side by side in ghastly rows awaiting, some, the recognition of friends who came to claim them, but most, for the rite of simple sepulture at the hands of kind strangers in that quiet village by the sea.”

Appropriately, Mr. Osmers concludes his book with a section on Montauk’s Lost at Sea Memorial, with lists of “Lost at Sea Memorial Inscriptions” and “Keepers and Officers in Charge of Montauk Life-Saving and Coast Guard Stations.”

Generously illustrated with 86 historical black-and-white photographs, Mr. Osmers’s work succinctly relates a general history of the U.S. Life-Saving Service and offers insight into valiant attempts to save lives and property in Montauk. It is a valuable account of an important piece of the history of Montauk.

The Ditch Plain Life-Saving Station, shown in 1885.

Montauk Point Lighthouse Museum Photo

John Eilertsen is the director of the Bridgehampton Museum.

Henry Osmers is the tour guide and historian at the Montauk Lighthouse.