How Glackens Found His Voice

It could not have been easy to be an American artist at the turn of the 20th century and the years to follow.

Playing catch-up with the revolutionary movements of European modern art must have been discouraging at the very least to the young artists who tried. Those who did may have been dismissed by unsympathetic audiences or shunned entirely by fellow artists for not pursuing a more nativist vision.

The career of William Glackens, who is being showcased with a survey at the Parrish Art Museum through Oct. 13, is emblematic of the times he lived in and the choices available to artists of that era.

Born in 1870, he came of age in 19th-century Philadelphia, a talented and popular student at an advanced high school that emphasized art. It was there he befriended Albert Barnes, who would become a leader in bringing French Modernism to America, based initially on the recommendations and purchases of Glackens.

He attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and became an illustrator for local newspapers. Robert Henri and John Sloan, who championed unadorned renderings of the working classes, brought him into their circle, which came to be known as the Ashcan School. Glackens adopted their approach, but tempered it with a more French sensibility.

Glackens also had a strong career as an illustrator that continued after a move to New York in 1896, where he landed regular assignments from Collier’s and Harper’s and reported on the Spanish-American War for McClure’s. The exhibition includes a good variety of illustrations that show his strong ability as a draftsman as well as his populist sensibility.

His early art was shaped by James McNeill Whistler in its tonality, and, while he was viewing the work of the French Impressionists, it was the somber lessons of Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas that lingered in his paintings from 1895 to around 1908. The first years were shaped by a trip to Europe, where he studied French and Flemish art. The last year was pivotal in producing the exhibition of artists from Henri’s circle who would become known as “the Eight.” Similar to the French Impressionists’ Salon des Refuses, it marked one of the first revolts from the National Academy of Design and a move toward more freedom of expression for American artists.

Many of his earlier works seem to be painted at night and underwater, with otherwise lighthearted park scenes looking murkily akin to a funeral cortege by Gustav Courbet. “May Day, Central Park” from 1904 was one of the paintings he chose for the show that is also in this exhibition. It depicts a tangled crowd of children, exuberant if not unruly, with the few adults doing little to promote order. The painting is a collection of figure studies, capturing the human body in a variety of poses, accurately but in the sketchy style of the Impressionists. The white dresses of some of the girls add mere highlights to an otherwise moody green landscape.

A shift can begin to be seen in another work exhibited in both shows, “View of West Hartford” from 1907. Gone are the dark undertones; a sunny sky actually looks sunny, and the landscape is open and rolling in contrast to his often oppressive views of urban parks. As the exhibition of the Eight traveled the country through 1908, the artist continued to lighten his palette, experimenting not just with Impressionistic renderings that refer to the brighter colors of Pierre-Auguste Renoir, but also leaping past the 19th century to the hues of Henri Matisse during his Fauvist phase. Both artists would become major inspirations in Glackens’s mature work.

These early forays are represented by “Vaudeville Team” from 1908-9 and “Cape Cod Pier” from 1908. Both are highly successful, if derivative. He continued in this vein for a while, expanding the expressive use of his color while often grounding it in darker undertones. His American city and waterfront scenes are clearly defined, but the expressive use of color is markedly French and would continue to be so throughout his career.

The Parrish installed the exhibition thematically to mixed responses, but it works over all. A purely chronological show may have underscored the nuances between individual works executed days or months apart, as this artist was clearly working hard to find a unique voice within and between the modern movements. Yet, the urban, fashion, seascape, and still-life sections allow these differences to be seen over the years in a meaningful, like-versus-like way.

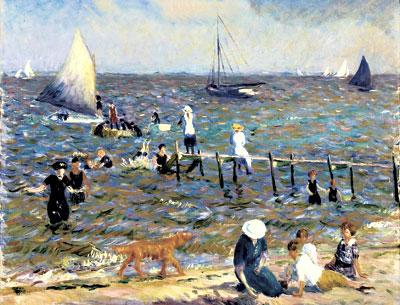

The seascapes he painted at Bellport during 1911 to 1916 demonstrate his experiments with color, prompting him to say to Barnes during a visit there that he could see the entire spectrum of color in the water, where Barnes said he could only see blue and green. This is noticeable in paintings such as “The Little Pier” and “Summer Day, Bellport.”

The quality of the artwork varies, and when contrasted with the radical advances that continued in Europe (the Cubist experiments of Picasso and Braque were under way in 1909) seems quite tame. By the 1930s, American Social Realists had caught up with him and his peers, but his handling of ladies at a soda fountain from that time looks anachronistic compared to the modern setting and clothes. In his later works and still lifes, one wishes to see more Paul Cezanne than Renoir, whose oeuvre makes up a significant portion of the Barnes Collection, often to its detriment.

Still, there is much to be said for any artist (particularly Glackens, who also worked on the 1913 Armory Show that introduced European and American modern art to the country on a broad scale) willing to adopt the demimonde subject matter and avant-garde techniques of the Europeans at that time. It was an open-mindedness that would help other American artists see how the painting of modern life would also need to be different from the world they had previously known.

The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalog.