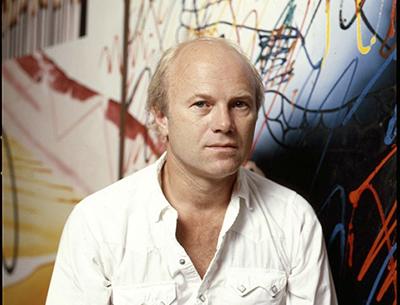

James Rosenquist, Pop Pioneer

James Rosenquist, a progenitor of Pop Art who expanded its scale and developed a painterly language marked by the juxtaposition of fragmented and disjunctive images, died at home in New York City on Friday after a long illness. He was 83.

His best known art, which encapsulated many of his concerns, was “F-111,” an 86-foot-long work he began in 1964 that took as its subject the F-111 fighter plane, parts of which were interspersed with images of a rubber tire, a child beneath a hair dryer, lightbulbs, spaghetti, and more, all rendered with eye-popping colors and cartoon-like imagery.

Describing that painting, he said the plane was “flying through the flak of consumer society to question the collusion between the Vietnam death machine, consumerism, the media, and advertising.” While there is no denying the painting’s political message, he nevertheless responded to a question from the Icelandic painter Erro, saying, “It was more about composition. I’d do anything for composition. I’d tear things up.”

According to Terrie Sultan, director of the Parrish Art Museum, “James Rosenquist’s iconic works definitively heralded a new direction in American painting. Along with his creative colleagues Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, Rosenquist charted the territory of Pop Art beginning in the 1960s and continuing to today. A master technician and inspired thinker, Rosenquist brought his real-world experience as a professional sign painter into the realm of high art.”

Writing about Mr. Rosenquist’s work for The East Hampton Star, the late Robert Long said, “No other painter understands as well as he does the power of juxtaposition; no other painter has used images from popular culture with such extraordinary force.” He also pointed out that the Rosenquist works reproduce easily but deceptively, because, up close, “You can see brushstrokes, and underpainting, and even marks where masking tape has been ripped away from the canvas.”

Born in Grand Forks, N.D., on Nov. 29, 1933, to Louis and Ruth Rosenquist, he moved to New York City in 1955 after three years of art study at the University of Minnesota. He said one of his teachers, Cameron Booth, “told me to get out of the Midwest and go to New York and study with Hans Hofmann. But Hofmann wasn’t there when I got there.”

Instead, he studied for a year with George Grosz and Edwin Dickinson at the Art Students League, and he moved to Coenties Slip in Lower Manhattan, where the artists Jack Youngerman, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana, and Agnes Martin had studios. During those early years, until 1960, his day job was painting billboards, but he was otherwise an abstract painter.

According to Sarah Bancroft, who organized Mr. Rosenquist’s 2003 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum, the painting “Zone” (1960-61) was the breakthrough that left abstraction behind and utilized “jarring shifts of scale and content for which the artist is known.”

Some established art critics, however, dismissed his and other Pop artists’ work. One noteworthy dust-up occurred in 1972 between Mr. Rosenquist and the New York Times critic John Canaday. In a letter published in The Times, the artist said, “Mr. Canaday has revealed himself over my work in the past when my ‘F-111’ painting was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum. He disliked this immensely.” Mr. Canaday was subsequently criticized by Thomas Hoving, then the museum’s director.

Mr. Rosenquist lived in East Hampton from 1964 until the mid-1970s. He also had houses in Bedford, N.Y., Miami, and Aripeka, Fla., where a fire in 2009 destroyed his house, office, and studio and much of his work.

His first marriage, to Mary Lou Adams, ended in divorce. His survivors include Mimi Thompson, his wife since 1987, a son, John Rosenquist, from his first marriage, a daughter, Lily, from his second marriage, and a grandson.