James Salter’s Character Sketches

“Don’t Save Anything”

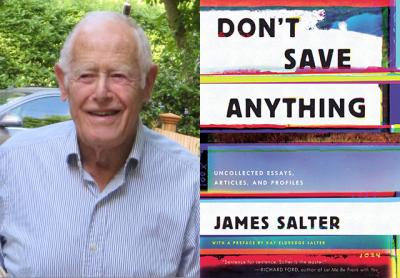

James Salter

Counterpoint, $26

It is a near certainty in publishing that when a writer of renown passes away, a year or so later a haphazard collection will appear in bookstores. It is almost always a flimsy thing, this book, which may include some uncollected magazine pieces, a few poignant letters, a book review or two, some lost poems — any scraps the writer’s estate can find to pad what is advertised as the final word of a great writer. Twenty-six dollars, please.

This was the fear in learning the daunting title of a new book of nonfiction by James Salter (who died in 2015), “Don’t Save Anything: Uncollected Essays, Articles, and Profiles.”

Happily, as it turns out, the title is misleading. As the writer’s wife, Kay Eldredge Salter, states in her preface, “don’t save anything” refers to a notion her husband held about his own work. To paraphrase: Resist the temptation to hold material for later use. Throw everything in now. In fact, most of the pieces included in “Don’t Save Anything” are more than serviceable, and a handful indispensable, many of them, as Ms. Salter states, rescued from boxes the writer had “stored in places I could only get to with a ladder.”

It is astonishing now to think that a writer of Salter’s prestige once wrote for People magazine. But that is exactly what happened in the mid-1970s, when he was sent to Europe to profile writers such as Graham Greene, Vladimir Nabokov, and Antonia Fraser. (Different magazine, different world.) All three pieces are collected here, each showing Salter’s gift for brief portraiture. Of waiting to meet the Nabokovs at their hotel in Montreux, he writes, “The great chandeliers hang silent. The tables in the vast dining room overlooking the lake are spread with white cloth and silver as if for dinners before the war.” Of Nabokov himself, he states, “Novelists, like dictators, have long reigns.”

I would dare to venture that such sentences, and subjects, have not appeared in the magazine since.

An essay on his literary hero, Isaac Babel, crystallizes the Russian writer’s genius. “The strength,” Salter writes, “came not when you could no longer add a sentence but when you could no longer take one away.” Salter imagines Babel’s last moments before his execution by Stalin’s regime in 1940: “What he felt as he walked to the chamber or courtyard in which he would be executed, shaken and alone, we cannot know. It may have been memories, his wife, daughter, even the fate of the folders of manuscripts that had been taken from him. Then, standing or kneeling near a wall, like countless others, he was shot.”

Not all the pieces here have the same heft. In “Passionate Falsehoods,” Salter remembers his work in film, and shows he is not above a bit of name-dropping. There is a light romp for The New York Times in which he takes to the Austrian slopes with the legendary skier Toni Sailer, and another about eating in France that culminates with a recipe for figs served with a Scotch whiskey sauce. Even among the fluff, however, one can find genuine literary pleasures. In “Passionate Falsehoods,” Salter writes of hanging out with Robert Redford, just then on the cusp of mega-stardom, “There was a dreamlike quality also, perhaps because Redford seemed to just be passing through, not really involved. It was washing over him, like a casual love affair.”

The one misfire might be the essay titled “Younger Women, Older Men,” written for Esquire in the early ’90s. While advocating the erotic tension of disparity — “the woman’s age should be one half that of the man’s plus seven years” — Salter includes brief fictional sketches meant to illuminate his theme. Instead, these fragments — unmoored from a larger whole — are carried off with precious descriptions of exotically named beauties nestled among the trappings of leisure. “She had a slight accent, South America, Rome?” “They order a good wine — Raoul knows these things.” The timing, also, couldn’t be worse. While Salter never endorses anything perverse or untoward, the specter of Roy Moore and #MeToo casts a pall that makes for uneasy reading.

Again, what one cherishes here most are the biographical sketches, displaying the author’s keen eye for what was once known as character. An appraisal of Dwight D. Eisenhower, for example, almost single-handedly revives Ike’s beleaguered reputation. “Those who think of him only as president, an old crock with a putter, fail to see the man as he really was. He was tough, resilient, wise.” Somehow Salter makes us believe it.

But it is an evocation of the Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio that is perhaps the collection’s piece de resistance. D’Annunzio is a Salter hero writ large — louche, romantic, libertine, staunchly European, and, like Salter himself, a former fighter pilot. For 20 sublime pages the profiler sinks his teeth into his subject and doesn’t let go. About one of the poet’s famous works, “Alcyone,” the author writes, “It describes the sensations of a Tuscan summer, the sounds, smells, glare, the burning noons. Many of the poems are of astonishing beauty. . . .”

Much the same could be said of the work of James Salter, this valedictory collection proving once again his place among the essential American writers of the last half-century.

Kurt Wenzel is a novelist who lives in Springs.

James Salter lived in Bridgehampton.