In the Key of Prayer

“Without a Claim”

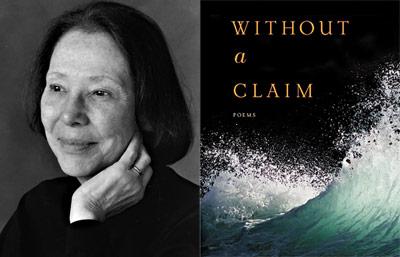

Grace Schulman

Mariner Books, $14.95

“The land was ours before we were the land’s,” wrote Robert Frost — famously and infamously. Brazenly entitled, bizarrely defensive, Frost’s “The Gift Outright” has been the source of controversy ever since the bard recited his poem at the 1961 presidential inauguration, when his hair was as wintry as his wisdom, and his eyes failed to read the poem he’d actually written for the occasion. Although “The Gift Outright” admits of nuance — such as is contained in the troubling 13th line (“the deed of gift was many deeds of war”) or the magisterial close (“such as she was, such as she would become”) — discerning minds have difficulty accepting its message of America’s manifest destiny.

In her seventh collection of poems, “Without a Claim,” Grace Schulman swaps Frost’s tenet for that of many Native American tribes (whose dispossession “The Gift Outright” ignores). The title poem openly rebukes all pioneering swagger:

This land we call our place was never ours.

If it belonged to anyone, it was

the Montauk chief who traded it for mirrors,

knowing it wasn’t his.

Ms. Schulman’s assertion is refreshingly clear, and clarity is her principal attribute. Indeed, detractors will deride “Without a Claim” for the same quality others will admire: accessibility. Perspicuity may be a privilege of her age — Ms. Schulman is 78 — as well as her keen, and comfortable, sense of place. Her poems are rigged with the seascapes and hamlets of Long Island’s East End:

Accabonac, Shinnecock, Peconic, Napeague,

the creek, the bay, the stream, the Sound, the sounds

of consonants, hard c’s and k’s. Atlantic,

the ocean’s surge, the clicks of waves

collapsed on rocks in corrugated waters . . .

Poets of praise are, I think, often given to litanies. Look no further than Whitman, whose influence on Ms. Schulman came early and has been continual. Albeit quieter than her precursor, Ms. Schulman is also a poet of praise. Even the titles of her poems announce her optimism: “Celebration,” “In Praise of Shards,” “Love in the Afternoon.”

However, throughout “Without a Claim,” Ms. Schulman seems compelled to answer for her hopefulness, time and again acknowledging the fear, pain, and misunderstanding in the world that trouble hope.

In “My Father’s Watches,” for example, the poet remembers her father’s Sunday ritual when she was a girl: “he brought us smoked fish . . . then combed files of letters / from his parents in Poland, / hoping they were still alive.” Later in the poem, the young poet tries to assuage her father’s anxiety by reading him her verse. Sadly, she recognizes:

. . . no words

could mute the drone

of planes in his head.

To which the mature poet responds, unsurprisingly, in the key of prayer: She wishes for time enough to “write lines / [her] father might hear / over bombs and gunfire.”

If not in its healing power, Ms. Schulman at least seems confident in the permanence of art. In “Chauvet,” she muses on the meaning behind the early cave paintings found there:

. . . Some say the cave was an altar,

the beasts sacred, but I think the task

was to get it right, the horse’s leap,

the faun’s terror, the lion’s charge, knowing

that in a life of change those animals

would stay. They have. . . .

What Ms. Schulman finds enduring in art — and the imagination — is its sense of unity and wholeness. Reflecting on a broken whelk, she writes:

I see the ruined shell

as I might gaze

at the headless statues

of gods and imagine

their eyes whole.

The problem, however, is that wholeness is incongruent with our lives. And Ms. Schulman knows this. “Why does the mind reach for completeness when the fragments are all we have?” she asks. As for the permanence of art, there is too much evidence to the contrary. Art can — and probably will — fade. To preserve against the same damage wrought in Lascaux, Chauvet has been closed to the public for nearly two decades. Will the image, as Ms. Schulman suggests, really stay? Does it matter if no one is around to experience it?

It may be unreasonable to expect poetry to satisfactorily answer these questions, yet these are the questions Ms. Schulman poses in her book. Rather than wallow in doubt, she tends to place her trust in epiphanies, accept that “all work is unfinished by definition,” or elide matters with a wish. Just how convincing her poetry of praise is depends upon a reader’s acceptance of the language of prayer.

Will Schutt won the 2012 Yale Younger Poets Prize. He is the author of “Westerly,” a collection of poems published in April, and lives part time in Wainscott.

Grace Schulman, distinguished professor of English at Baruch College, lives in Manhattan and Springs. “Without a Claim” came out on Sept. 10.