Kids These Days

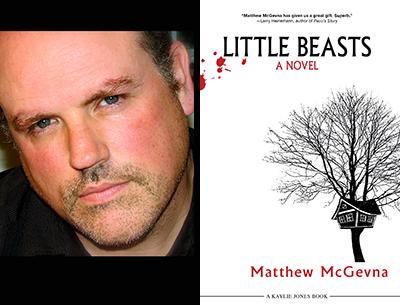

“Little Beasts”

Matthew McGevna

Akashic Books, $15.95

Let me begin by skipping a reviewer’s reserve and saying up front that I loved the idea of “Little Beasts” before I read a word: A young writer who could have stayed in his pajamas downing energy drinks and composing Internet “content” and Twitter posts instead practically took up residence in a bunker-like public library in an aging strip mall in Shirley to obsessively research a 1979 murder that haunted his childhood.

When four teenagers killed a 13-year-old behind a Smithtown school by stuffing rocks down his throat it became a cautionary tale for kids like Matthew McGevna, who went on to fictionalize it into his debut novel in a tried-and true attempt to get at the crux of the matter through storytelling. After all, there must have been more at work in the horror than the ill will of a few Long Island dirtbags.

Bourgeois niceties do not apply. Mr. McGevna has fashioned a gripping exploration of teenage alienation and temporary depravity that’s all the more so for its working-class setting. That would be hardscrabble Turnbull, based on the Shirley and Mastic Beach area, where the author grew up.

The novel opens with a poignant dissection of an eviction, a common occurrence that three local boys, James, Dallas, and Felix, turn into a chance for spying and adventure as the gorilla movers toss stick furniture and bad motel room art into a pile out front that by all rights should simply be set aflame. Inside, social services and bankruptcy attorney phone numbers are penciled on a kitchen wall, notes from a disintegrating life.

Stimulation is wanting in Turnbull. It’s the early 1980s, and these kids are so bored they’ll get themselves chased out of Zambrini’s Brick and Masonry yard just for fun.

What they do have is the woods — the pull of coursing the winding footpaths, befriending stray dogs, and brazenly raiding other kids’ forts for materials to build their own. Naturally that’s where the trouble starts.

Mr. McGevna sets two distinct storylines on trajectories for collision, the other involving a sensitive 15-year-old, David Westwood, who is artistic and somewhat politically aware — he’s skeptical of Reagan-era jingoism, at least. He has a couple of sketchy friends, but at school he’s ostracized. Adding to his isolation is a lonely home life in which his mother waits tables at Windmills Diner and his father works a double shift as a security guard at a King Kullen “in a rich town farther east.”

The psychological portrait of David is astute, and thus sympathetic. After he is branded a commie over a mural he painted, he retreats, for instance holing up in the school library, where he pores over encyclopedias in search of arcane facts, as though “tearing up the floorboards of the world and discovering what lay beneath.” (“The umbrella was not originally intended for rain,” he tells his girlfriend as he stands soaked on her doorstep. “It was intended for shade from the Egyptian sun.”)

Though he is taunted, he’s not exactly bullied, a la Klebold and Harris of Columbine fame, and though he is an outcast, there is always the “rejected camaraderie,” as Mr. McGevna puts it, of fellow losers. No, David’s halfhearted dumping by a girl he is too much in love with, who in turn is enamored with an in-crowd football player, is emotionally crippling, compounding his other largely self-inflicted agonies.

Mr. McGevna has a lot to say here, come courtroom time memorably skewering the local press’s nonsense pontificating, hasty conclusions, presumption of intimate knowledge, and thudding, metaphor-mixing prose: “To look at David Westwood’s sketchbook is to gaze down the barrel of a mind poised on the edge of destruction.”

More galling still, this windbag columnist sees his fortunes rise at the expense of a confused adolescent, echoing a kind of a karmic seesawing experienced elsewhere in the novel, as when the murder victim’s devoutly Christian dad is brought low, while a surviving friend’s useless drunk of a father, Ivan, is so moved by the funeral service, with its invocations of the trials of Job, that he quits the bottle and re-examines what he’s doing with his life.

Renewingly so, you might say: In bed with his wife, “For the first time in years, she gripped his hand and drew him to her.”

As Ivan would later tell his young son — about a bruise, a weakness, a circumstance, you name it — “Don’t worry. A thing doesn’t stay ugly forever.”

Matthew McGevna has an M.F.A. in creative writing from Southampton College. He lives in Center Moriches with his wife and two children.