Life as a Non Sequitur

Here’s how it went: Kurt Vonnegut Jr. was at a posh Bastille Day brunch at an oceanfront East Hampton home. A young woman, newly arrived on the East End, trying to make conversation over the smoked salmon tray, offered: “Oh, I’m from Indianapolis, too.” Whereupon Vonnegut, of the rumpled face and sweet, bovine eyes, said: “My mother committed suicide. She should have done it a lot earlier.”

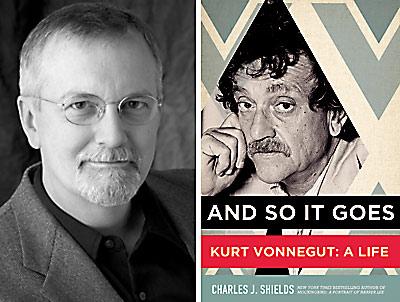

“And So It Goes”

Charles J. Shields

Henry Holt, $30

If anything, what Charles J. Shields proves in his well-researched, well-reasoned biography is that Kurt Vonnegut’s life was a non sequitur. Nothing flowed logically.

Take, for example, his name: Born in 1922, he was the third child. The oldest, Bernard, a scientific genius, didn’t get the appellation “Jr.” Kurt Vonnegut Jr., the least favored of the children, was once told point-blank: “You were an accident.”

Vonnegut’s parents were among the richest in the Hoosier capital city. When the Depression hit, the family lost most of its money. But they went right on spending despite the fact that they were unable to sell their fancy house. His father was an architect and responsible for a truly remarkable engineering feat: He moved an entire office building, the Indiana Bell Building, with all the workers doing their job in it. The edifice was winched up and moved 52 feet forward from its foundation and then swung around. Even the elevators continued to operate during the incredible maneuvers. But despite a triumph that brought observers from all over the globe, Vonnegut Sr. couldn’t prosper as an architect or engineer.

“Kurt Vonnegut:

Novels & Stories,

1963-1973”

Edited by Sidney Offit

Library of America, $35

Big brother Bernard insisted Vonnegut Jr. study science at Cornell, where he loved writing for the student paper. But in science classes things really weren’t going well. It was World War II. Vonnegut decided to enlist. By then his parents had finally moved to a smaller Indianapolis house, which his mother roamed, Lady MacBeth-like, all night long. He got a military pass to come home. But it was too late: On Mother’s Day when he was 21 the family found Edith dead from an overdose of sleeping pills. She had not left a note. He had not gotten to see her that weekend.

As a P.O.W. Vonnegut’s experiences were devastating. And then came the bombing of Dresden. Coming up out of the bowels of the earth where he was imprisoned, he was forced to search shards of buildings for days to find and stack rotting corpses. He was barely alive himself. Some of his starving fellow soldiers were shot when they found and pocketed bits of food. The images, the horrors, were indelible. Masterfully Mr. Shields uses a Dostoyevsky phrase that Jane, Vonnegut’s first wife, provided him: “One sacred memory from childhood is perhaps the best education.”

Upon Vonnegut’s return from war, Bernard, a puppet master, finagled a job for his brother with his own employer, G.E. Vonnegut, newly wedded, was thrilled with the job as a flack for a scientific concern. But soon he earned the dismay of his employers because he was too busy writing his own stories. Some of which were published. Many not. He quit his cushy job anyway. Editors such as Knox Burger nurtured him enormously.

“Harrison Bergeron” (get it?), originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, appeared in “Welcome to the Monkey House” in 1968. The story centers on a constitutional stipulation that each American is completely equal — no one is weaker, slower, uglier, or less intelligent than anyone else. The story takes place in the year 2081. There’s even a Handicapper General and a swat team of agents. The problem is a beautiful, graceful ballerina. She has to wear a mask as well as weights around her ankles, which is figuratively what Vonnegut had to do his entire life.

Vonnegut once provided a list of rules for aspiring writers that were, of course, contradictory — and these rules carry both the sweetness occasionally manifested in him as well as his orneriness. Here are a few: Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted. Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them. Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia. To heck with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on that they could finish the story themselves should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

Mr. Shields is the author of “Mockingbird,” a biography of Harper Lee, who is a very different type of writer and whose personality, although feisty, can’t be more different from Vonnegut’s. It is clear that Vonnegut’s widow, the photographer Jill Krementz, did not cooperate with this biographer. That she is depicted as a harridan is putting it mildly. And perhaps as a result the photograph albums included in the book are not particularly interesting or revelatory. Indeed, Vonnegut is barely recognizable in most of the photos. Another nitpick: Mr. Shields misspells the name of the town of Southampton — surprising given the fact that much of Vonnegut’s later story takes place in Sagaponack.

The Shields biography could perhaps have benefited from a more intense examination of Vonnegut’s novels and short stories. However, the recently issued Library of America omnibus contains many of Vonnegut’s finest works in a handsome collection, and it’s perhaps best for readers to return to the original. In Vonnegut’s case there’s a great deal of prescience. In “Breakfast of Champions,” also titled by Vonnegut as “Goodbye Blue Monday,” his famed Kilgore Trout (the author’s alter ego) makes an appearance. The book, which takes place in Midland City (hmm, wonder how the Indiana author thought that one up), involves “two lonesome, skinny, fairly old white men on a planet which was dying fast.”

In “Cat’s Cradle,” Vonnegut’s fourth novel, a satire of the arms race, Felix Hoenikker is the fictional co-creator of the atomic bomb.

Then there’s “Slaughterhouse-Five” and Billy Pilgrim, the alien from Tralfamadore, who witnesses the bombing of Dresden. The book’s succinct subtitle? “The Children’s Crusade: A Duty Dance With Death, by Kurt Vonnegut, a Fourth-Generation German-American Now Living in Easy Circumstances on Cape Cod [and Smoking Too Much], Who, as an American Infantry Scout Hors de Combat, as a Prisoner of War, Witnessed the Fire Bombing of Dresden, Germany, ‘The Florence of the Elbe,’ a Long Time Ago, and Survived to Tell the Tale. This Is a Novel Somewhat in the Telegraphic Schizophrenic Manner of Tales of the Planet Tralfamadore, Where the Flying Saucers Come From. Peace.”

Is there any wonder why this author who was made to feel apart from the heartland, apart from his parental home, his marital homes, his children, from everything, would not be alien-obsessed? Mr. Shields points out that Vonnegut often felt dismissed as just a sci-fi writer by the literary establishment. But of course “Slaughterhouse-Five” was named the 18th greatest novel in English of the 20th century by the Modern Library. That’s how it went.

—

Kurt Vonnegut died in 2007.

Laura Wells is an editor and writer who lives in Sag Harbor.