Lit and Lies in the Cold War

“The Unwitting”

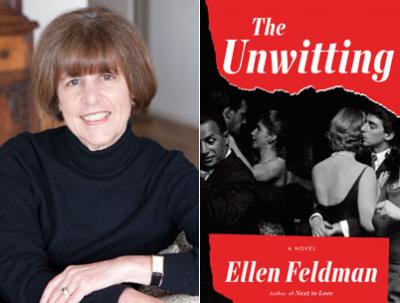

Ellen Feldman

Spiegel & Grau, $26

When the writer and naturalist Peter Matthiessen died last April, one of the most surprising aspects of his obituaries for many was the reminder of his involvement with the C.I.A. and the money the agency poured into The Paris Review during its early days. Just why would spies care about an artsy journal read by the literati?

In the magazine’s inaugural issue William Styron wrote: “I think The Paris Review should welcome . . . the good writers and good poets, the non-drumbeaters and non-axe-grinders. So long as they’re good.” Doesn’t sound like much of a manifesto for overthrowing totalitarian regimes, does it? But for decades the agency deemed the work of a left-wing journal crucial in its fight against communism.

In her novel “The Unwitting” Ellen Feldman takes us back to the ’50s and ’60s, to Cold War insanity and McCarthy red scares. Through the prism of one loving marriage we see more clearly why and how people made the choices they did. Her analysis of that evolution is fascinating.

Here is a précis of “The Unwitting” — in C.I.A. parlance a “witting” is one of the handful of people who know whence the money is being funneled. Nell, the narrator, falls madly in love with Charlie. They marry. Nell, a bit of a rabble-rouser, becomes an investigative reporter. Charlie is named editor of a literary magazine, Compass, and begins earning a decent wage. (Yes! The red flags began waving for this reader at that very moment!) Nonetheless, the two dote on their daughter, Abby, they revel in their ideological discussions, they lead earnest, fulfilling lives. Then on the day John F. Kennedy is assassinated, Charlie is murdered in Central Park. Nell goes about unraveling the mystery of who her husband actually was.

One of the themes Ms. Feldman has explored soul-searchingly in this and some of her other novels is marriage, its extraordinary complications, and the myriad fears of infidelity, as well as the devastating repercussions when there is — are? — one or more affairs in a marriage. She has plumbed those depths in her extraordinarily evocative and extremely well-researched novel “Lucy,” the behind-the-scenes story of Lucy Mercer Rutherford, Eleanor Roosevelt’s secretary, and her affair with Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

In “The Unwitting” Nell does wonder about whether or not her husband is straying. But the truth is that she is the one who ends up cheating when fate puts her on a trip to Soviet Russia along with her pre-husband boyfriend with whom she had a pregnancy scare just before she met Charlie. “What kind of a girl starts the day in love with one man and ends it inside the coat of another?” (Ms. Feldman also skillfully interweaves ’50s and ’60s black-white complications. Woody, her former boyfriend, now an N.A.A.C.P. lawyer, is black. Nell is white.)

Ironically Charlie’s infidelity is not with another woman but with his becoming a Witting and leaving her out of a major part of his life. “Trust isn’t a cup of sugar you can borrow from a neighbor when the household supply runs out,” Nell thinks. Throughout the novel she fights with the concepts of reliability and honesty. In rereading a letter Charlie wrote to her, she is taken aback as she analyzes his hedging of his bets: “You are my love. And my conscience. And my touchstone. You keep me honest, or as honest as I can be.”

Ruefully she remembers another moment. “ ‘You know as much as I do.’ He held up his right hand. ‘Scout’s honor.’ Odd that I didn’t believe him when he was telling the truth but that I fell for his lies. No, not lies, evasions and omissions.”

In a discussion of Executive Order 10450 Ms. Feldman gives us yet another insight into the craziness of the time. Eisenhower had signed into law demonstrations that the rationale behind disloyalty included negative views of one’s “character, morality, and behavior.”

“In other words, the government could destroy your life and put you in prison for drinking, gossiping, and screwing around, favorite pastimes of just about everyone we knew.”

Charlie is hauled to Washington to be interviewed by a pair of close-cropped Kafkaesque goons. Again the theme is about trust within the marriage. Ms. Feldman reminds us of so much that happened during the Cold War that has faded from public knowledge, including that which happened to a number of literary, journalistic, and artistic figures. She mentions Mary McCarthy, and East Enders such as Robert Lowell and Sydney Gruson, an important New York Times executive whose career in Central America has been manipulated by the C.I.A.

“Nell was right,” Charlie wrote in his diary, one given to Nell long after his death. “It was no accident that Sydney Gruson was pulled off the Guatemala story. Someone at the CIA was spreading rumors around the Times that Gruson was a dangerous radical with communist connections and therefore not the correspondent to cover the overthrow of a left-leaning president.”

Nell pays a horrifying visit to Soviet Russia during the course of the novel, accompanying a road company of “Porgy and Bess.” There she sees the extraordinary suffering repression and human rights abuses can cause. She goes on to discuss the C.I.A. and its desire to present other versions of the up-and-coming arts scene to the Soviets in the form of — astonishingly enough — Jackson Pollock!

“Gossip said the CIA, with the help of Modern Art and certain critics, had made popular the new school of painting, which they saw as the opposite of dull, prescribed Soviet realism. Here was the spirit of American individualism, vibrating in living color on larger-than-life canvases. The Agency’s darling was said to be Jackson Pollock. Instead of an effete European-influenced artist, our national painter was a hard-drinking, hard-driving, all-American who wore cowboy boots and painted from the hip.”

One evening, three and a half years after her husband’s unsolved murder, Nell catches a Mike Wallace special on television: “This is a report on a fantastic web of CIA entanglements, an almost comical intelligence debacle that reached into every corner of American life — academia, student organizations, labor unions, magazines, newspapers, and more.” Nell is handed the coup de grâce: Her husband is named. “March 13, 1967: the night I grew up. . . . In this world, naïveté is irresponsible, but willful naïveté is criminal.”

There are occasional lapses in the book. Characters seemingly contradict themselves, which, admittedly, is part of human nature. Nell is a slightly argumentative, often contradictory figure. In a very few instances the language she uses exceeds the grasp of one telling her own story, as evidenced when she calls her own nose “retroussé.”

Yet in “The Unwitting” Ms. Feldman tackles astonishingly complicated topics. She has carefully, delicately unraveled so many networks without pointing fingers. She writes about secrets and secret keepers, those who hoist the dissemination of misinformation to an art form. Her narrator asks serious questions throughout. Her husband, the literary fellow who wanted to do right by his country by publishing and not publishing materials according to certain C.I.A. dictates, is a complex, often distant figure.

Ms. Feldman negotiates these complexities so expertly that the reader is never confused. She has done her homework well, even enlisting experts such as Stacy Schiff, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer, to be the reader of her drafts. Ms. Feldman is a novelist who cares about the facts, ma’am. Who knows that using real, somewhat obfuscated stories can create the most compelling of fictions.

At one point Elliot, who becomes Nell’s lover, then fiancé after Charlie’s death, and who is head of the foundation that poured money into Charlie’s literary magazine, tells her: “It didn’t take much to persuade [Charlie] that what we needed was a good left-wing anti-Soviet magazine.” In some ways the C.I.A. was far more generous in its support of the nation’s arts and cultural entities than the federal government’s arts and humanities arms designated for that very purpose. Ms. Feldman’s characters relish such ironies.

Laura Wells is a regular contributor of book reviews to The Star. She lives in Sag Harbor.

Ellen Feldman lives in New York and East Hampton.