A Little Encouragement

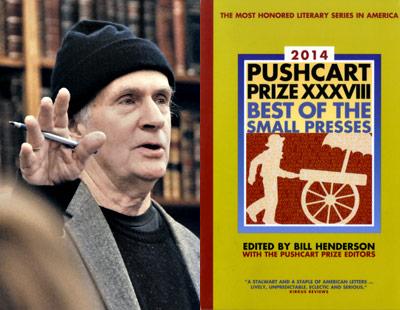

“The Pushcart Prize XXXVIII”

Edited by Bill Henderson

Norton, $19.95

Bill Henderson: Here’s a guy who saw that something was missing in the literary landscape. Hey, this man who had been a player in mainstream publishing uncovered gaps in the intellectual terra firma. Lapses in the American literary emotional playing field. The idea behind Pushcart? So much beautiful writing is published in small journals but seen by too few people. Why not go on a treasure hunt, find the best, then highlight the works, make sure that they are brought to the attention of a much wider audience.

Thirty-eight years ago Mr. Henderson began redressing literary voids by creating a prize. Not a press. A prize. Do good: You will be rewarded. Do poorly: Well, that’s our little secret. He began letting the presses know that even more people cared. He was also saying: Because all those presses have believed in the power of writing and have slaved to create a safe haven, a soapbox, a podium, they also deserve recognition and encouragement to keep on fighting for literature.

This edition is replete with writing that alerts us to the power of imagination. The strong-arming of emotion. Take Amy Hempel’s searing “A Full-Service Animal Shelter,” which ran in Tin House. The short story takes us into an extraordinary world — that of a city-run facility in Spanish Harlem where dogs that are not adopted are euthanized. Through the eyes of a volunteer trying desperately to give the dogs quality of life, we see the horrors of bureaucracy, cruelty — as well as the extraordinary kindness of many strangers.

“They knew us as the ones who got tetanus shots and rabies shots — the latter still a series but no longer in the stomach — and who closed the bites and gashes on our arms with Krazy glue — not the medical grade, but the kind you find at hardware stores — instead of going to the ER for stitches, where we would have had to report the dog, who would then be put to death.”

Others of the 69 selections in The Pushcart that stand out as the best of the best of the best: In Louise Gluck’s “A Summer Garden” (Poetry), she writes: “How quiet it is, how silent, / like an afternoon in Pompeii.” Lorrie Moore’s “Wings” (Paris Review), which is included in her new collection of short stories, starts with this very funny line: “The grumblings of their stomachs were intertwined and unassignable.”

In the beginning of Charles Baxter’s “What Happens in Hell” (Ploughshares), the humorist relates a question he was once asked: “ ‘Sir, I am wondering — have you considered lately what happens in Hell?’ No, I hadn’t,” he notes, “but I liked that ‘lately.’ ” In “Your Body Down in Gold” (Sugar House Review), the poet Carl Phillips conveys a different mordant set of thoughts: “saying / aloud to no one I have decided how I would / like to live my life, and it isn’t / this way . . .”

But a true killer piece? Andre Dubus III and his essay “Writing & Publishing a Memoir: What the Hell Have I Done?” which originally ran in River Teeth. Mr. Dubus muses over whether the persona he presents in his memoir is his true self or whether it’s a completely different character. His musings go to the heart of the matter for all memoirists. Have I got this right? Am I being too kind to myself? Am I trying to atone for my sins? Or am I creating a bad boy (or girl) image simply for the sake of causing a sensation?

Mr. Dubus quotes the writer Janet Burroway, saying that when readers pick up a novel what they’re actually saying is: “ ‘Give me me.’ ” Mr. Dubus talks about looking out at an audience as he’s about to give a talk: “. . . please don’t confuse me with that Andre in the book; he’s a character and I’m real. That was then, and this is now.”

And then something magical happens: “. . . they stopped clapping and the hall grew quiet. I could hear the rain on the roof and against the windows, and I could see so many of their faces — expectant, slightly wounded, hungry for something helpful, many masking this hunger, and I felt the younger Andre, the only one they knew, descend into my legs and arms and chest and face. Then we were both stepping toward the microphone, and together, we began to speak.”

A review of the anthology in Publishers Weekly makes an extremely valid point: “With large publishing houses facing an uncertain future, the Pushcart Prize is more valuable than ever in highlighting the treasured voices thriving in America’s small presses.”

But the battle the Pushcart Prize is waging is larger even than that. The National Endowment for the Arts has been foundering. Funding has been severely cut back, and the organization has been without a chairperson for over a year. (The same is true for the National Endowment for the Humanities.) A candidate is currently being vetted. But if, in a liberal administration, the arts are not “treasured” by the federal government, many of the small presses and literary reviews have a much harder time existing.

One wonderful touch in this edition is the dedication: “For Harvey Shapiro (1924-2013); Poet, editor, friend.” Shapiro lived here on the East End for many decades. A longtime editor of The New York Times Book Review, he was extraordinarily generous with other writers and editors. He was also a very fine poet. It was Harvey Shapiro who told the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that the next time he was incarcerated he should write about the experience. The result? “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” a stirring document during the civil rights movement. What Shapiro understood deeply was the need for encouragement, which is what Mr. Henderson also supports wholeheartedly.

Forty years ago Pushcart Prize editors began their search. And all those presses whose editors took the time to nominate the works they felt were the strongest? Mr. Henderson makes sure they’re listed in the PP. Along with their addresses, so that we can track down the publications and editors whose sensibilities mesh most closely with our own.

Laura Wells, a regular book reviewer for The Star, lives in Sag Harbor.

Bill Henderson lives in Springs.