Long Island Books: By Any Other Name

“Averse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell,” wrote Currer Bell, alias Charlotte Bronte, going on to explain in her flowing style why she and her sisters, Anne and Emily, sought anonymity:

____

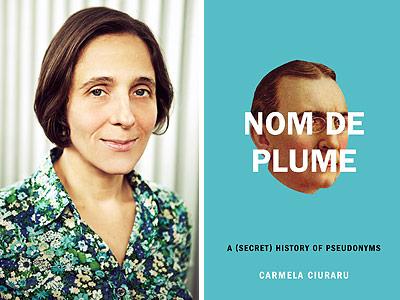

Nom de Plume:

A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms

Carmela Ciuraru

Harper, $24.99

____

“The ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women because — without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called ‘feminine’ — we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice; we had noticed how critics sometimes use for their chastisement the weapon of personality, and for their reward, a flattery, which is not true praise.” Simply put, women were not supposed to write books in 19th-century England.

Only after her death was Charlotte Bronte’s explanation printed in editions of “Wuthering Heights” and “Agnes Grey.”

In “Nom de Plume: A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms,” Carmela Ciuraru reveals the fascinating variety of reasons why the Bronte sisters wrote as the Bells, why Aurore Dupin wrote as George Sand, why Marian Evans became George Eliot, why Charles Dodgson penned his way down the rabbit hole as Lewis Carroll.

The curtain is raised on 19 writers in all, and while the diverse motives behind their choosing anonymity are what the author said inspired her to write the book, her clear, anti-pedantic style of presenting the lives and times of her subjects makes it a page-turner.

In August, Ms. Ciuraru visited the Montauk Book Shop to discuss her book. She pointed out that “nom de plume” was not a French phrase. It was an English invention. The French refer to a pen name as a “nom de guerre,” which in the case of a few of her subjects seems more fitting. O. Henry is a case in point.

Some say that O. Henry, alias William Sydney Porter, was one of the finest American writers of short stories. He once told an inquiring reporter that his decision to write under an assumed name stemmed from chronic “shyness,” but his shyness was certainly compounded by the fact that William Sydney Porter had been convicted of embezzling money from the First National Bank of Austin, where he worked for a time.

On the other hand, Samuel Clemens hid behind Mark Twain to accommodate his doppelganger. Ms. Ciuraru tells us that Twain called himself “an independent double,” and his biographer Ron Powers wrote that Twain’s “indifference to the boundary between fact and fantasy became a hallmark of literature, and later, of his consciousness.”

The Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa was not an independent double so much as an extremely dependent Hydra. “I’ve divided all my humanness among the various authors whom I’ve served as literary executor. I subsist as a kind of medium of myself, but I’m less real than the others, less substantial, less personal, and easily influenced by them all.” Pessoa called himself “a drama divided into people instead of acts.”

If Eric Blair had kept his given name, we would be calling the excesses of totalitarian states “Blairian” instead of Orwellian. He grew up in Edwardian England, the product of two prominent families. As a young man, he said it was an era that held “the sheer vulgar fatness of wealth without any kind of aristocratic elegance to redeem it.” He had bad lungs and was at times bedridden, which made him sensitive to “disparities in social condition.” Blair was extremely superstitious. He believed a pseudonym would prevent anyone from using his real name against him for evil purposes.

He attended Eton, worked in India for the Indian Imperial Police, but did a three-sixty, decided to live among the common folk of Paris, where he indulged in prostitutes, and London, where he dressed as a tramp and slept in Trafalgar Square. The experience resulted in “Down and Out in Paris and London.” George Orwell might have been a handle meant to save his family embarrassment, but it was the vehicle that allowed him to leave an ambivalent time behind.

George Sand (Aurore Dupin), and George Eliot (Marian Evans) were women who wrote under men’s names. Sand, a bohemian, seemed to grow into her androgyny. Eliot, from a small village, needed a shield against repercussions that would surely result from her “autobiographical ideas abut religion, faith, and unrequited love,” Ms. Ciuraru writes.

“Whatever may be the success of my stories, I shall be resolute in preserving my incognito, having observed that a nom de plume secures all the advantages without the disagreeables of reputation,” Eliot wrote to her editor’s brother.

Karen Blixen was a Dane, the granddaughter of a shipping magnate. Her father was a writer who, as “Boganis” (American Indian for “hazelnut”), wrote “Letters From the Hunt,” an account of his adventures in America. Blixen grew up in East Africa, as readers of “Out of Africa” will recall, but returned to Denmark to write as her father had. Her decision to become Isak Dinesen came from the same desire as her father’s, to “express himself freely, give his imagination a free rein. He didn’t want people to ask, ‘Do you really mean that?’ Or, ‘Have you, yourself, experienced that?’ ”

Ms. Ciuraru writes that Blixen’s name change allowed her to start fresh after the painful losses of her father to suicide, her farm in Africa, and her husband, Fenys Finch Hatton, in a plane crash.

“ ‘Must a name mean something?’ Alice asked doubtfully. ‘Of course it must,’ Humpty Dumpty said, with a short laugh. ‘My name means the shape I am, and a good handsome shape it is, too. With a name like yours, you might be any shape.’ ”

Charles Dodgson became Lewis Carroll because “my constant aim is to remain, personally, unknown to the world.” “Lewis Carroll” was a hiding place for this strange, Victorian, obsessive-compulsive mathematician with a penchant, as a boy, for naming the snails and toads in the family garden, and his curious attraction to young girls later in life.

There is not room here to delve into all of Ms. Ciuraru’s subjects, although the chapter on Patricia Highsmith (a virulent anti-Semite who would not allow her books to be published in Israel, and who smuggled her pet snails into France in her underwear), alias Clare Morgan, is a novel in itself. And Pauline Reage (Dominque Aury) remained under cover to distance herself from her own pornography.

Such delicious insights, but the real reward, the lasting stimulus of “Nom de Plume,” lies in the curiosity it generates to read or reread the fruits of the furtive — “Wuthering Heights,” “Tom Sawyer,” “The Gift of the Magi,” “Alice in Wonderland,” “Histoire de Ma Vie,” “A Clergyman’s Daughter,” “Middlemarch,” “Scenes of Clerical Life,” “Strangers on a Train,” “The Story of O,” on and on and on.

—

Carmela Ciuraru lives in Brooklyn and Sag Harbor.