Long Island Books: Bad Business

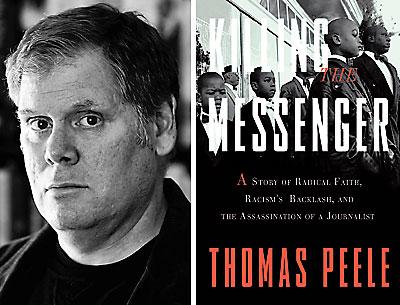

“Killing the Messenger”

Thomas Peele

Crown, $26

On Aug. 2, 2007, a 19-year-old male wielding a handheld shotgun killed the editor of The Oakland Post, a small, free, weekly newspaper in California. The killer had followed the orders given him by his 21-year-old employer, Yusuf Bey IV. Chauncey Bailey, his newspaper career tumbling in an avalanche of misfortune, seemed to be an unlikely target for murder, but he had written an unflattering story about an Oakland institution, Your Black Muslim Bakery.

What Bailey had written was not the kind of story usually published by The Oakland Post, in which black business success stories were used to herald community progress. Nor was Bailey’s story about the bakery exceptionally well written. In fact, The Post’s publisher had refused to print it because it lacked attribution. But Yusuf Bey IV, who had been head of the bakery for two years, did not know the paper had refused to publish its editor’s negative story about the bakery’s nefarious business activities.

Fourth, as he was called, became head of Your Black Muslim Bakery after his brother, four years older, was killed, possibly at the behest of Fourth. Yusuf Bey IV was ill equipped to manage the complex business enterprises established by his father, Yusuf Bey, consisting of one semi-legitimate business, the bakery, and numerous scams. Your Black Muslim Bakery made and sold banana cakes and fish sandwiches in the black community, a much healthier menu than white people/corporations offered to blacks, Bey claimed. The success of the bakery, however, depended heavily on the forced labor of women and children. Much of the rest of Bey’s enterprise depended on welfare payments for the children of the women and girls he enslaved and impregnated behind the walls of the bakery.

Yusuf Bey, a k a Joseph Stephens, had been a “coiffeur with panache,” styling the hair of white women. After he converted to the Black Muslim religion and changed his name, he claimed he wanted to help his people. In addition, though, he wanted to become rich and to take any woman he desired to be his sexual partner. When he was criticized by leaders of the Black Muslims, he disassociated himself from the Black Muslim faith, but “clung to their rhetoric and preached their radical faith to his breakaway sect,” convincing many to give themselves totally to his version of the faith. While preaching self-determination, Bey “held absolute power over his followers, controlling when they worked, ate, and spoke, when and where they slept, what they wore, where they went.”

In his weekly TV program, he preached that drugs were the devils’ (white people) way of suppressing and destroying blacks and preached against drinking alcohol. He also preached black superiority and stressed the “inferiority of other races, especially whites and Jews.” He recruited and trained a small army made up mostly of released convicts. They were, ostensibly, employees of Your Black Muslim Bakery, paid for by government grants for training and employment. The ex-con army was used to intimidate anyone who opposed Bey.

His group controlled areas of Oakland that had been a problem for the overworked Oakland police force. Because the crime rate went down in the area around Your Black Muslim Bakery, the police practically withdrew, leaving the neighborhood in the hands of Bey and his men. The bakery obtained repeated government loans and grants that supported the army and, at the same time, a lavish lifestyle for Bey. The good life for Yusuf Bey lasted nearly 30 years.

Under his fictional version of Islam, Bey justified both polygamy and sex with young girls as perfectly permissible. Eventually, some of the women he had abused banded together to file charges because their children, even their grandchildren in some cases, were being raped and enslaved. Finally, 27 rape charges were filed, Bey was arrested, and bail was set at $1 million. By that time, Bey was terminally ill. He was able to delay a trial long enough to die without being convicted. With no conviction for his crimes, those among his women and children who were loyal could claim his innocence, and Your Black Muslim Bakery was left to his heirs.

Yusuf Bey had founded his business on the philosophical base of the Black Muslim faith, but as he moved forward he concentrated on his personal goals — power, money, and sex. His son and successor, Yusuf Bey IV, seemed to have little use for religion when he, still a teenager, first took over the bakery and its related enterprises. He also lacked the charisma and administrative ability of his father. As his inherited empire crumbled around him, he began studying the early words of the religious people his father had followed. He began thinking of himself as special, as having a divine calling. Despite the evidence that things were not going well in his empire, he believed himself to be protected.

That kind of magical thinking must have led him to believe he would suffer no repercussions if he sent his soldiers to kill the journalist, Chauncey Bailey, who had written a negative story about him and Your Black Muslim Bakery. He was almost right. He almost got away with a brutal murder.

Why he did not is what makes this one of the most important books I have read in the past decade. If I had the persuasive ability of Yusuf Bey, who persuaded officials to award some large grants to Your Black Muslim Bakery, perhaps I could persuade every elected official and every government employee, especially those in law enforcement, to read this book. Then I’d recruit ordinary citizens to read “Killing the Messenger,” especially people who think that no problems for our country will emerge from the differences in opportunity and lifestyle between the absurdly rich and the staggeringly poor.

Just as Bey cajoled government officials into giving him money, if I had his ability I’d cajole religious fundamentalists to read this book. I mean those who believe their brand of religion should be the only religion for our democracy. “Killing the Messenger” is more than a nonfiction thriller, it is, perhaps unintentionally, a commentary on some of the major problems that face our country.

This book reminds us all of the importance of the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States because, ultimately, it was good old-fashioned journalism that brought justice to the murderers of Chauncey Bailey. When it was known that he might have been murdered because of a story he had written, the Chauncey Bailey Project was formed and journalists from many regions assembled in Oakland.

Thomas Peele, the author of this book, was part of the project. For four years, dozens of investigative stories were written and published, finally exposing the facts about Your Black Muslim Bakery, the Oakland Police Department, and government officials who had developed selective vision in the expenditure of public funds when it was expedient to do so. Money from universities, foundations, and organizations supported the project. On the basis of this cooperative journalistic endeavor, Yusuf Bey IV and his henchmen were arrested, tried, and convicted for the murder of Chauncey Bailey.

In the late 1960s, I was the minister of a mostly white church in a mostly black neighborhood in Pittsburgh, a stronghold, along with Detroit, of the Black Muslim faith. A group of white ministers held regular meetings with the leaders of the Black Muslims to promote understanding and cooperation through dialogue. In those meetings we heard about the forces of racism that gave root to their movement. In “Killing the Messenger,” the author also provides a summary of the historical context out of which a radical such as Yusuf Bey could manipulate a community and have the kind of impact on a city that Bey had in Oakland. On page 66, the author recounts what was happening when Southern blacks were migrating to the industrial areas of the North:

“The Klan was growing rapidly in the North. Membership in Michigan eventually exceeded 800,000, the largest of any state. At rallies in the hinterlands, Klansmen claimed Detroit should be the exclusive domain of Caucasians. Klan membership in Detroit grew from a few thousand in 1921 to 22,000 less than two years later. As ballot counters began tallying the results of the 1923 municipal elections, crosses burned outside city hall. On Christmas Eve, the Klan placed a giant, oil-soaked cross downtown. A man dressed as Santa Claus ignited it, and four thousand men encircling the conflagration bowed their heads, reciting the Lord’s Prayer.”

It is extremely important that readers of this book have a clear understanding of the history of prejudice and intimidation. Without this context for the emergence of the Black Muslim movement, the reader might easily drift into new layers of prejudice and be tempted to assign characteristics of the few described in this narrative to the many. Complex forces brought about the Black Muslim movement, and eventually the events in Oakland, culminating in the murder of the black writer Chauncey Bailey.

Not even the history of suffering among blacks in the North can soften the horrible crimes and abuses that were inflicted on people in Oakland and documented in “Killing the Messenger.” However, without the historical reference provided in a dramatic, although brief, section of the book, I fear information about the events in Oakland as described might not only affirm racial bias but also give credence to individuals and organizations that oppose worthwhile social programs for struggling neighborhoods that need them.

The First Amendment prohibits the making of any law impeding the exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, or infringing on the freedom of the press, as well as other protections. This galvanizing book, “Killing the Messenger: A Story of Radical Faith, Racism’s Backlash, and the Assassination of a Journalist,” may be uncomfortable to read because it reminds us how terribly fragile and violable those precious First Amendment rights are, even in an established, pluralistic society. Despite that discomfort, it should be read and appreciated as an important and timely book.

Thomas Peele is an investigative reporter for the Bay Area News Group. He grew up in East Hampton and graduated from East Hampton High School.

Gary Reiswig is the author of “The Thousand Mile Stare: One Family’s Journey Through the Struggle and Science of Alzheimer’s.” He lives in Springs.