Long Island Books: Boozing, Brawling, Bookish

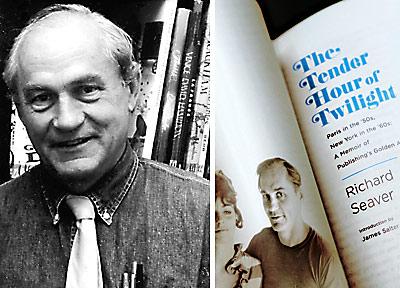

“The Tender Hour

of Twilight”

Richard Seaver

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $35

No review can do justice to this incredibly rich memoir of publishing’s golden age — Paris in the ’50s and New York in the ’60s. At best what follows is just a sketch. You will really have to read Richard Seaver’s masterpiece for yourself. Buy “The Tender Hour of Twilight” at an independent bookstore, Canio’s or BookHampton — it is a celebration of the heyday of such stores long before the metastasis of the e-book, chains, and Amazon.com.

Imagine! In the ’50s and ’60s publishing was fun! Authors and editors knew each other, celebrated, fought, and cried together. Bottom-line corporate hacks were unknown. Small presses and tiny bookstores struggled to survive and did the truly valuable work of discovering new literary talent.

And editors like Seaver were at the center of it all. This vivid recollection — wonderfully edited by Seaver’s widow, Jeannette (he died in 2009), immerses the reader in that era.

Seaver journeyed to Paris after graduation from the University of North Carolina and a brief stint as a teacher and wrestling coach at Connecticut’s Pomfret School. He won an American Field Service Fellowship and headed off to France expecting to find a whiff of the long-gone Hemingway and Fitzgerald magic. A decade later, I too set off seeking the same whiff. Seaver and I stayed at the same Left Bank hotel, 21 Rue Jacob, he for 30 cents a night, but by the time I arrived such a room cost $1.40 a night. I briefly planned to start a magazine titled Patterns but thankfully the notion expired.

Like many an expat, Seaver got by teaching English to the French, at Berlitz, and also to Air France stewardesses at Orly Airport. To get to Orly he biked from Paris on his Peugeot (Big Blue) — a three-hour round trip.

Seaver was there at the start of a little English language journal called Merlin, which kept the faith for a few years after an initial funding from a founding editor’s dad in, of all places, Limerick, Me. Early on Seaver and Merlin championed an unknown named Samuel Beckett: “the most exciting writer I have read since I’ve come to Paris . . . he had just turned forty-five . . . for God’s sake, and nobody was reading him!”

Seaver set out to rectify that oblivion at Merlin and later in New York at Barney Rosset’s Grove Press. He devoured everything that Beckett wrote and attended the first performance (in French) of “Waiting for Godot” at a nearly empty Left Bank theater. The reviews were not enthusiastic.

Beckett was reclusive and Seaver labored long to meet him. He describes their first encounter:

We’d all but given up hope of ever hearing from Beckett when, one dark and stormy early evening in late November . . . a knock came at the door. The noise of the rain on the glass roof up above was so deafening we barely heard the knock. When finally I answered, there, outlined in the light, was a tall gaunt figure in a raincoat, water streaming down from the brim of the nondescript hat jammed onto the top of his head. From inside the folds of his raincoat he fished a package, not even wrapped against the downpour: a manuscript bound in a black imitation-leather binder.

“You asked me for this,” he said, thrusting the package into my hand. “Here it is.”

It was the manuscript for his novel “Watt.” Beckett disappeared into the night.

Other Paris notables of the era were not so hard to meet. Brendan Behan, a stranger to Seaver, arrived at Seaver’s room one night thusly:

“SEAVER! I’m looking for RICHARD SEAVER. HIMSELF! I know you’re in there, SO OPEN UP!”

. . . “WHO IS IT?” I shouted, trying hard to match the door-side decibels.

“BRENDAN,” the voice said. “BRENDAN BEHAN’S THE NAME. SO OPEN THE FUCK UP! WE NEED TO TALK.”

And so Brendan Behan, boozing all the while, moved right in.

Merlin and George Plimpton’s Paris Review were rivals of sorts in the Paris of the 1950s. Also present was the ambitious publisher of Olympia Press erotica, Maurice Girodias, who briefly hooked up with Merlin to distribute Merlin books. But Seaver’s Parisian odyssey was about to end. The Navy called him up in his reserve status and he and his new French wife, Jeannette, headed to the Boston Naval Base to await future orders.

Before he left, Seaver received a letter from a New Yorker, Barney Rosset, who had read his piece on Beckett in Merlin number 2 and wanted to meet him in Paris. Rosset had just bought the failing Grove Press for $3,000 and was hunting for authors.

“Barney was a slight, intense, wired-up young man whom I judged to be in his early thirties, although his receding hairline made him look older,” Seaver writes of their first meeting. “He was wearing thick horn-rimmed glasses, and when he laughed — which he did often, though nervously, as if he weren’t quite sure a laugh was appropriate to the remark — he looked strangely equine, baring both gums.”

Their association would last over a decade and change the literature of the century. In New York, Seaver found Grove Press to be “a beehive of scuffle and scurry.” Grove was about to publish the first unexpurgated “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” by D.H. Lawrence, a sure lightning rod for censorship — along with 60-plus other titles by Frank O’Hara, Henry Miller, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, John Rechy, and all of Samuel Beckett. The censoring lawsuits against “Chatterley” and other titles were endless and threatened to bankrupt Grove, but Seaver and Rosset soldiered on and forever altered what was permissible to publish. (Rosset died last week.)

The high point of the ’60s included two amazing eyewitness accounts. At the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention the Seavers escorted the French writer Jean Genet through what amounted to a police riot wonderfully recalled by Seaver. Two years later, in April 1970, Grove’s offices were invaded by a women’s liberation group demanding union representation. They took over Rosset’s office and threatened to burn years of invaluable correspondence. Again Seaver was the center of the action, trying to calm red-hot passions.

Soon thereafter the house Barney built suffered a startling financial collapse. Seaver started his own imprint at Viking and later was publisher of Holt, Rinehart, and Winston before founding Arcade Publishing in 1989, which he and Jeannette ran until his death. Arcade published over 500 books by authors from 30 countries and was a beacon as one of the last independent literary houses.

For me at Pushcart he is no less than a hero. What he did in Paris and at Grove is an inspiration for thousands of writers and editors in today’s small-press movement. We insist, as Seaver did, that literature should never be just about money. It comes from the heart, and publishing is a matter of guts and daring and not the bottom line.

If there is any sadness to be noted in this review let it go on record that Seaver was a beautiful writer. I only wish he had written more and not devoted 100 percent of his life to other authors.

Richard Seaver had a house in Southampton.

Bill Henderson publishes the Pushcart Press in Springs. His latest book is a memoir, “All My Dogs: A Life.”