Long Island Books: Boyhood Dreams

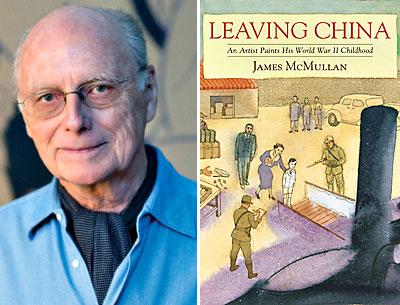

“Leaving China”

James McMullan

Algonquin, $19.95

Before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941 and so entered World War II, war had been raging between China and Japan for four years. In 1937, long-simmering tensions burst into warfare, as the Japanese rapidly occupied large swaths of China. One family’s life in that time and place is revealed to beautiful effect in James McMullan’s graphic memoir, “Leaving China.”

In full-page watercolor paintings, each matched with a brief elucidation of some moment of the author’s childhood, frequently placed in historical context, that world is brought to life in lovely, poetic detail. Though the book is aimed at young readers, one wonders if it won’t appeal even more to adults interested in this period of history and in the emotional development of a young artist.

Mr. McMullan’s family began its Chinese sojourn as missionaries. His Irish grandfather and British grandmother met in Yangchow in 1887, when both had come to work with the China Inland Mission, a Protestant missionary group. They settled in Cheefoo, a northern port city, where they encountered dire poverty and widespread female infanticide. Devoting themselves to the cause of saving the babies regularly abandoned in a cemetery tower nearby, they eventually founded an orphanage.

As the fortunes of Cheefoo improved, fewer babies were abandoned, and the McMullans turned their attention to establishing an embroidery school, where the girls learned to make lace and embroider the local silk and cotton. Their efforts were so successful that these girls — English-speaking, Christian, and trained in a craft — became more valued in the marriage market than girls who had been raised by their own families. The James McMullan Company exported the lace and embroidery made by the girls.

Alongside this business venture, the McMullans founded their own missionary organization, the Cheefoo Industrial Mission. The pair’s four children — among them the author’s father — would continue both the evangelical and the business strains of their parents’ accomplishments, making a comfortable life for their own families in Cheefoo.

Mr. McMullan offers a rare and fascinating glimpse into expatriate life in the prewar China of his earliest childhood. Describing his musician father playing songs from “Anything Goes,” he tells his reader, “Those popular songs and movies influenced much of what my father and mother wore, what they drank, and how they arranged their social life. It was for them a special connection (and a style tutorial) to that fabulous world very far away from Cheefoo.”

This stylish expatriate life is pictured in gorgeous watercolors, where purple shadows fall from majestic porches, his young mother selects flowers from the garden in a pink gown, and his father stages musicals at the community theater, chorus girls lined up beneath the stage.

The McMullans held luncheons in a cottage overlooking the ocean, took part in endless balls, dressed up for costume parties. This social whirl stood in contrast to the austere missionary life Mr. McMullan’s grandparents had come to Cheefoo to lead, and he tells us, “Occasionally, I would overhear my father proclaiming that they must stop all this partygoing and lead more Christian lives.”

It was, of course, not their moral rigor but the war that ended the partygoing and set the author’s life on a new path. When the British Consulate instructed British citizens to leave in 1941, the family quickly lost its wealth and James and his mother embarked on a peripatetic life, while his father joined the British Army to fight for the Chinese. Moving from Shanghai to San Francisco to Seattle to Vancouver to a family home in the Gulf Islands off the western coast of Canada, as Mr. McMullan tells it, “My mother and I were now wanderers, not yet attached to any particular place and without any clear destination.”

The story is captivating enough, but Mr. McMullan brings to it the dreamlike sheen of childhood memory, infusing these long-past events with the glow of lost time and the bittersweet taste of a long-ago family pulled apart by war, but also by the emotional push and pull that animates all families. James and his mother both are haunted by the fear that they will disappoint his father, a war hero. Sadly, their fears seem justified. The young McMullan is nervous, not masculine enough to please a father who barks, “Oh, for God’s sakes, be a man!” at his 10-year-old son, who cries as his parents leave him at his new boarding school in India.

The emotional divide between father and son, and the artistic son’s anxiety as he realizes that he will not be the kind of man his father wants him to be, is beautifully illustrated in the watercolors. In the early years in Cheefoo, we see the father playing piano while his son plays with toys on the floor. They occupy opposite ends of the room, separated by stark lines of rug and light, and they don’t look at each other, each absorbed in his own activity.

This distance would never be crossed; Mr. McMullan’s father was killed in a plane crash a month after the end of the war. Some of the most evocative writing describes Mr. McMullan’s complicated feelings in the wake of his father’s death.

The loveliest moments of the narrative — both verbal and visual — are those where we step away from the historical framework and enter the pure sensorial memory of childhood. We might glimpse the young artist’s perceptions as he describes “that moment when the sun coming through the tall windows would be carved into clear rectangles on the carpet into which I could steer my trucks and cars as if they were entering a city of light.”

Or we might hear of darker times in Cheefoo under Japanese control, in which the young McMullan hears Japanese soldiers running outside at night — again we get the dreamlike consciousness of the child: “I lay in bed listening to this ominous percussion and imagining many of the bad things my parents had assured me were never going to happen.”

Or, at another moment his enchantment with his aunt’s beautiful house on Salt Spring Island, as he recognizes “how much comfort I found in the intelligence of my visual surroundings.” There are many moments of such simple beauty, and a reader can spend hours exploring the watercolors that so powerfully convey these childhood fears and early glimmerings of artistic leanings.

Those leanings would eventually take the shape of a very successful career, one in which Mr. McMullan, a Sag Harbor resident, has illustrated posters for Lincoln Center musicals (including “Anything Goes,” which his parents so loved in Cheefoo), a New York magazine piece on 1970s discos in Brooklyn that would inspire the movie “Saturday Night Fever,” book jackets that continue to turn up on bookstore shelves, and popular picture books written by his wife, Kate McMullan.

Mr. McMullan has said that it was only recently, in his 70s, that “I began to recognize and accept how much my boyhood self is a large part of who I am today, and how much his anxieties and enthusiasms are the underground river always bubbling up in the tone of what I draw and paint.”

Readers should be glad that he did come to this realization, and that he chose to share it in the breathtaking form of “Leaving China.”

Sasha Watson is the author of “Vidalia in Paris,” a young-adult novel. A onetime reporter at The Star, she lives in Los Angeles and has a family house on North Haven.