Long Island Books: A Family’s Life in Letters

“The Nicolls of

Sachem’s Neck”

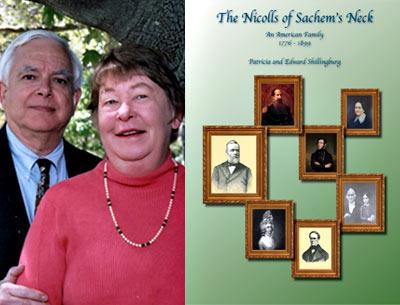

Patricia and Edward Shillingburg

Cedar Grove Press, $25

Have you ever wondered what the rest of the letter said, when you come across a mystifying tidbit reprinted in a book of letters where the editor has made selections all too sparingly, and without enough commentary to fill in the gaps?

Here to satisfy that need are 19 correspondents of a prominent Long Island family anchored on Shelter Island, who provide epistolary portholes into a history that slowly drifts through three centuries from the mid-17th century to the end of the 19th. They write to and about each other and their world, which included New York City, and their times, which covered the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, politics both local and national, the shift on Shelter Island from fishing to tourism, epidemics, and family deaths and illnesses, including alcoholism.

Charlotte Ann Nicoll (1827-1891), rightly identified by the editors as the heroine of “The Nicolls of Sachem’s Neck: An American Family, 1776-1899” as well as the person who saved the 350 letters now the property of the Shelter Island Historical Society, married a fashionable, rich, layabout cousin, Solomon Townsend Nicoll, who became deeply addicted to drink. Charlotte bore six children in rapid succession, as was the custom of the day, and carried on. Sol, as he was called, is swiftly depicted by the Shelter Island historians Patricia and Edward Shillingburg in a few deft strokes.

Much of Charlotte’s story is told by her children, and by “the aunts,” the unmarried sisters who helped her through her trials and who finished out their lives in Sag Harbor, in the handsome Federal house across the street from the Sag Harbor Elementary School on Route 114. Although women had few opportunities in the world, the best parts of this family history are woven of their thoughts, observations (sometimes wonderfully catty), searches for husbands, marriages, domestic duties, and quiet heroism.

Charlotte’s tale begins further back with two other young female cousins, dancing their hearts out with British officers in Revolutionary War New York in 1776 as the bodies of dead prisoners of war are silently — and nightly — dropped from the British vessels at anchor in the harbor. One, the gloriously named Gloriana Margaretta Nicoll (1750-1820), married John McAdam — yes, the inventor of the road-surfacing method that has given us the word “macadam” — and lived her life out in Great Britain. One of her letters, written to a nephew living at Sachem’s Neck, the family seat on Shelter Island that is now the Nature Conservancy’s 2,100-acre Mashomack Preserve, is printed in full.

Another, from Anne Charlotte DeLancy (1786-1852), who became McAdam’s second wife, written to her father in 1815 and also printed in full, is filled with cousins’ doings (the Nicolls’ world was composed chiefly of cousins) and lively descriptions: “Carolyn is a sweet affectionate girl. . . . Her eyes beautiful but her nose is not good and she has the abominable Carey Mouth from ear to ear but she is a darling girl I assure you.”

Readers will first wonder how to disentangle one story from another — and discover it doesn’t matter much as the red meat of the book is in the details set within the course of some quite ordinary lives, which, of course, are often the most fascinating lives. From time to time insular and genealogical interest obscures the wider view, as when James Fenimore Cooper, the author of “The Last of the Mohicans,” one of the most widely read novels in the world, the one that gave us both the stereotype of the American frontiersman and that of the noble red man, is described as an author of “40 adventure stories.”

There is nonetheless an eating-peanuts fascination to genealogical material, which, when parsed effectively here by the husband-and-wife Shillingburg team, exposes a family turning increasingly inward as the industrialized world diminishes the status of the family. It is as if they hardly know it, or don’t wish to recognize it, borne up as they are by their own history and bulwarked by a comforting sense of their own importance.

The first generations of men held significant colonywide governmental posts and derived their power from being the firstest with the mostest in the form of land acquisition (60 square miles in Islip, for example), while later generations became comfortable lawyers, doctors, and insurance men who nonetheless still owned rural acres on Shelter Island and houses in New York City. Only once do we hear about the world of Newport, R.I., and the Berkshires so well described by Edith Wharton and Henry James, when William Cortland Nicoll (1830-1901), one of Charlotte’s younger brothers, refers to the “Welthee” as he writes from his home in Flushing, his “quiet humble New England hamlet.”

The letters often capture the flavor of Shelter Island as the haven it was and is. In 1839, Charlotte’s older brother, 14-year-old Samuel Benjamin Nicoll (1825-1899), for this reviewer the liveliest letter writer of the 19 correspondents and the least obscure about his thoughts and feelings, wrote a Shelter Island fisherman’s lament to his father: “I have had but very little fishing this summer and when I went the walk was long, the time was short, the fish were small and few in number.”

His youngest sister, Anna Willett Nicoll (1844-1873), wrote a school composition sometime around 1854 that chronicles the delights of an island summer. It reads, in part, “the trees are covered with leaves and the grass looks green and the flowers in the garden and the flowers in the woods are in blossom and the birds sing and the lambs play.”

Read slowly and carefully, and with ample time to flip to the genealogy in back and to the useful tracking guides that head each chapter devoted to a single family member, “The Nicolls of Sachem’s Neck” will release the fragrances, both sweet and acrid, of what Edith Wharton, in her memoir, “A Backward Glance,” called “a life of leisure and amiable hospitality.”

Generous helpings from the book are posted on the website sachemsneck. com, including, for map lovers and for anyone interested in the evolving land use of Long Island, the section of the beautiful U.S. Coastal Survey Map of 1855 showing Shelter Island. A few black dots, scattered like dice, represent the houses, standing among the patchwork of fields that covers most of the island, crossed only by the roads leading to the old and new ferries.

Mac Griswold is the author of “The Manor: Three Centuries at a Slave Plantation on Long Island.” She lives in Sag Harbor.