Long Island Books: Like Father, Like Son

“In the Land

of the Living”

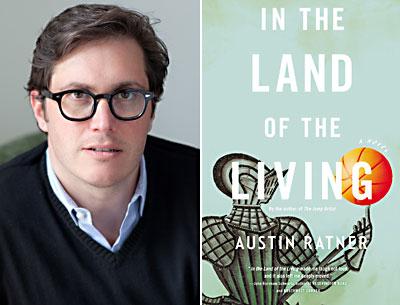

Austin Ratner

Reagan Arthur Books, $25.99

The follow-up to his award-winning debut, Austin Ratner’s second novel, “In the Land of the Living,” is the story of fathers and sons, stepfathers and surrogate fathers, brothers-in-arms and brothers estranged. It may be read as multiple bildungsromans; or as a tragic family saga of ambitious, fatherless men looking for acceptance in genteel — a k a gentile — America; or as a satire of manboys with congenital hemorrhoids.

The first section of the novel follows Isidore, the son of Jewish immigrants, as he comes of age in Cleveland. The family’s last name, Auberon, is a corruption of their Polish name, Abramowicz. Before long, Isidore’s mother dies of stomach cancer, and his father, Ezer, an abusive jack-of-all-trades, abandons his children to the care of foster homes and orphanages. By the “force of his personality,” Isidore gains access to the ivory tower, excels in medical school, and marries into a well-heeled family. Life’s a dream. Until, that is, Isidore dies abruptly, leaving behind two little boys of his own.

Isidore’s eldest son, Leo, is the protagonist of the second half of the novel. Like his father, he is ambitious, angry at the world, and hesitant to get a leg-up from his forebears. A straight-A student, he chooses to attend Yale over his father’s alma mater, Harvard, because: “To repair a legacy that lay in ruins was no easier or harder, he reasoned, than to start one from scratch. . . .” Or else, Mr. Ratner writes just a few lines later, “To use his legacy at Harvard would be to cheat and to lie to himself and leave the question open of just how strong he was.”

Mr. Ratner frequently attests to his characters’ brilliance, but little of their brilliance is ever on display. Despite the abundance of doctors in the novel, there’s seldom any mention of medicine. When not dropping demotic nothings (“There’s a huge painting of [Oliver Hazard] Perry in the capitol . . . It’s crazy-looking”), Isidore’s father-in-law, Dr. Neuwalder, the man supposedly responsible for curing sickle-cell anemia and inventing gene therapy, concocts implausible platitudes (“People say you live every day as if it’s your last — and maybe that works for people who have no idea what a last day on earth is like. I say, you live every day like you’re gonna live forever”) and Buddhist bromides (“It seems to me since then that a person’s a homunculus, and the child is the greater part of the self, and everything that comes after in life is in comparison a veneer”).

Medicine appears to be the least of anyone’s concerns, particularly Leo’s, who is more interested in shtupping Melody, the vegan from Portland, than in caring for the sick.

Melodys, Danielles, Dustys, Michelles: The women in “In the Land of the Living” live up to their bling name badges. Bailey from Brown is described as having “a French beauty about her, which is to say a dignified beauty cultivated like a crop by hundreds of years of genetic snobbery. . . . And mixed with her easy, stainless, French beauty was an American ruggedness and openness.”

As for Melody: “It seemed odd that [she] was single, since she was sexy with dark hair and a clear gentile face and had such a nice-smelling bathroom . . . Melody was very motherly in a certain way.”

Then there is Leo’s overblown love scene with busty Michelle from the University of Michigan: “[T]hey fit right together like two puzzle pieces meant for perfect apposition. He felt on his own chest the soft successive rise of hers against him, like the susurrant camber and retreat of waves on the sand. Her eyes were so alert and open and he was so close to them he could see splinters of topaz shining in her green irises.”

That this is a novel about fathers and sons does not excuse Mr. Ratner from plopping every woman under neon light; it is troubling to watch an author treat characters with so much uninspired fantasy. Many are described with the same blithe, generic observations Mr. Ratner makes about the cities Leo and his younger brother, Mack, drive through at the novel’s end: L.A. suffers smog, San Francisco steep hills, and Portland earnest vegans (vide Melody above).

Cleveland, Mr. Ratner’s hometown, is more convincingly drawn, and his portraits of children are genuinely funny and endearing. Yet the book is, ultimately, scattershot; there is too much Sturm und Drang for the story to be comic and too much cheap humor to call it tragic. Part of the trouble with defining “In the Land of the Living” stems from the novel’s radically inconsistent style. A reader is served Bruno Schulz for starters, James Joyce for an entree, and a slice of Judd Apatow to finish. Unfortunately, the perceptions of Leo and Isidore pale in comparison to “Portrait of the Artist,” and their Lost Boys attitude has less heart than “The 40-Year-Old Virgin.”

Will Schutt, who lives in Wainscott, won the 2012 Yale Younger Poets Prize. “Westerly,” a collection of his poems, will be published by Yale University Press next month.

Austin Ratner, the author of “The Jump Artist,” is a regular visitor to East Hampton, where he has family. He is clinical assistant professor of preventive medicine at the Stony Brook University School of Medicine.