Long Island Books: Round-Heeled Muse

Anne Roiphe is certainly a prolific writer. At the front of her latest book she lists 9 novels and 10 nonfiction works. “Art and Madness” is her third memoir. In it she goes back to her days as a very young woman, employing a somewhat confusing format by skipping back and forth in time between scenes from the 1950s and ’60s, creating an impressionistic mosaic of these years.

She covers marriage and motherhood, her prior student days at Smith and Sarah Lawrence, her upbringing by wealthy, emotionally estranged Jewish parents in their Park Avenue apartment, and her involvement with various writers from The Paris Review crowd.

The style is sweeping and high flown but the effect is confessional. With devastating honesty she recounts her abasement to the demands of the writers whom she revered. From the first meeting at the West End Bar with Jack Richardson, her darkly handsome, talented husband-to-be, he dazzles her with long, fluid monologues, and when he asks her to pick up the tab for his drinks, she doesn’t hesitate, offering as a bonus to drive him back to Queens, where he lives, she being the one with the money and the car.

A pattern is set for the dynamic of their relationship and subsequent marriage. She will work to support them both, and at night she will type up his manuscripts while he trolls the bars to pick up women and spend the money he has acquired pawning her china and jewelry: “He was not meant for the ordinary tasks of mortal days. Like Dracula he came to life at night, sleeping during the day with the shades pulled against the light. He survived on scotch and bourbon and cigarettes and German philosophy and French paperbacks. . . .”

cid and had become delusional.

___

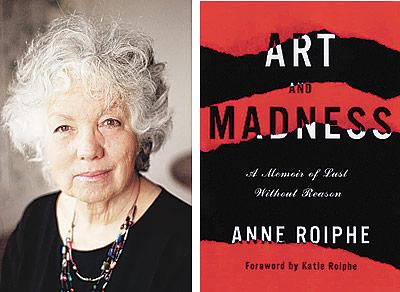

“Art and Madness”

Anne Roiphe

Nan A. Talese, $24.95

___

They both frequent parties at George Plimpton’s apartment, famous for the literary luminaries who had had their writing published in The Paris Review and gathered each Friday night to drink and pontificate. Harold Humes (known as Doc) had founded The Paris Review with Plimpton and Peter Matthiessen, but he had not weathered as well as they had, mainly because he was dropping a Since her husband was so blatantly unfaithful, she saw no reason not to respond in kind, but did she have to pick Doc Humes as the next famous writer in her bed? Even she admits that this was masochistic. By this time she has had a baby daughter — always referred to in her book as “the child” — with Jack Richardson, and she recounts an episode in which Doc phones in the middle of the night to tell her he is hearing voices and that someone has smashed his face into a mirror; he can feel cuts and blood gushing and yet when he looks in the uncracked mirror, he sees no injury to his face. He is panicked.

He tells her he will be dead by morning. She immediately bundles up the child, pulling a sweater over the baby’s pajamas, and hurries out to find a taxi and presumably save Doc from his demons. It is at this juncture that she tells the reader that despite her actions, her love for her child “is greater than all the seas that heave across the planet.”

I begin to suspect that Ms. Roiphe may be an unreliable narrator.

The memoir is naturally told exclusively from her point of view, and she is not only relentlessly self-involved, she is fanatically drawn to writing and writers (in college she had absorbed the works of Beckett, Sartre, and Camus, Steinbeck and Dos Passos, Hemingway and Fitzgerald, and, of course, the heartbreaking J.D. Salinger). She claims that “for me the art of the story, the written word, was worth dying for.”

While not a drinker herself, she says “alcohol was the lubricant of genius” and is drawn to the dramatic behavior it fuels because it satisfies her craving for the extreme, an attraction that is evident throughout the writing in “Art and Madness.”

After her marriage breaks up, she buys a little black notebook and, as though finally given permission, begins to write her own prose. She also continues to attend Plimpton’s parties, taking home sundry writers. By this time she is gaining some insight and makes a perceptive comment about the true nature of these gatherings: “Despite the heavy air of flirtation, the perfume of illicit sex that wafted through the book-filled rooms of George’s apartment, the game was something else. It was the famous men or the would-be-famous men flexing their skills, strutting their stuff. . . . It was the writers impressing each other, hoping to triumph over the one who was talking with an anecdote even more pointed, even more outrageous.”

Toward the end of the book the scene shifts to East Hampton, where she again socializes with writers and artists, in particular those with small children, playmates for her daughter: Jack Gelber, whose 1959 play, “The Connection,” was the first to explore the drug culture, Terry Southern, a casualty of that culture, Frank Conroy, Larry Rivers, and William Styron, who tends to turn up in various sex-and-alcohol-soaked memoirs.

Then abruptly she tires of fame; she begins to worry about its detrimental effects on the child. She starts dating doctors. She has a serious relationship with a Dr. Reiner, a psychoanalyst, and after him a psychologist, and then she meets Dr. Roiphe. The irony surely cannot have escaped her that having made such strenuous efforts to throw off the conventional restrictions of her parents’ upper-class Jewish background, she ends up in what is a classic Jewish joke: She marries a doctor.

Did she finally find contentment and an outlet for her passion for the written word? Well, she writes prodigiously and she was married to the same man for 40 years. Also, I notice that this memoir is dedicated to a Dr. Herman Roiphe.

—

Anne Roiphe had a house in Amagansett for many years.

Jennifer Hartig, a former Broadway stage actress, regularly reviews books for The Star. She lives in Noyac.