A Long Overdue Memorial

Fifty years ago in April, a 20-year-old from East Hampton was killed in action in South Vietnam. He would be East Hampton’s only casualty in Vietnam, and yet his ultimate sacrifice went unrecognized but for the friends who remembered him.

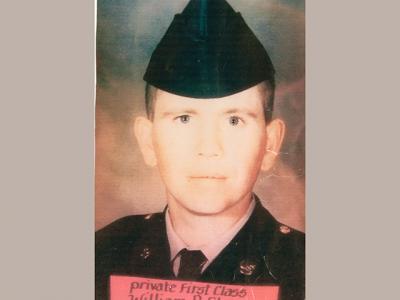

On Sunday, Veterans Day, a memorial was dedicated to Army Pvt. First Class William Patrick Flynn on North Main Street, just down the block from where he grew up. “It was long overdue,” said Sid Bye, a childhood friend of Private Flynn’s.

Private Flynn, who was known as Pat, was 19 when he was drafted into the Army in September 1967. “He was scared,” Mr. Bye said of his friend. The two met up during their leaves around Christmas at the bowling alley bar where everyone hung out in those days. “He told me it would have been easier but took more courage to go to Canada, than go to Vietnam. I didn’t understand what he meant by that until later,” he said.

After basic training at Fort Campbell, Ky., and then advanced infantry training at Fort McClellan, Ala., he left for Vietnam on March 22, 1968.

News of his April 28 death appeared in the May 19, 1968, edition of The East Hampton Star; his family first received word via telegram from the Army on May 5. The infantryman “was lost in a combat operation when engaged by hostile force in a fire fight,” the telegram read. Two days later, another telegram informed them that he had in fact been killed.

His mother, Margaret Flynn, told The Star at the time that her youngest son had been stationed in Chu Chi, near Saigon, with the 25th Division. The Army telegram did not specify the city where he was killed.

Mr. Bye learned of his friend’s death in letters from East Hampton. Some of his own letters to Pat that had never reached him were returned with a postmark noting that he was deceased.

Mr. Bye had tried over the years to memorialize his friend. He presented a petition to the East Hampton Town Board in the 1990s to have a new beach along the Napeague stretch named in Private Flynn’s honor. He thought it was a done deal, but nothing ever came of it, and as it turned out, he said, the town record made no mention of it.

Since then, the bridge from Sag Harbor to North Haven was renamed the Marine Lance Cpl. Jordan Haerter Veterans Memorial Bridge after a Sag Harbor native killed in Iraq in 2008. A 1.4-mile stretch of Route 114 was dedicated to Army First Lt. Joseph Theinert, who lost his life in Afghanistan in 2010.

As the 50th anniversary of Private Flynn’s death neared in April, Mr. Bye enlisted the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars in his efforts. John Geehreng, the commander of the V.F.W. who also knew Private Flynn, ran with it, Mr. Bye said. “If not now, when?” Mr. Geehreng asked.

With support from Bill Mott, commander of the East Hampton American Legion post, East Hampton Town board members, and village officials, they settled on placing a boulder with a plaque and benches on an existing but unused brick area by the entrance to the parking lot near the East Hampton Grill. “We thought this would absolutely be the appropriate location” — right along the path Private Flynn walked to school — said Town Councilman David Lys, who helped coordinate the effort.

A ceremony officially dedicating the spot to Private Flynn was held there on Sunday, followed by a lunch hosted by the East Hampton Fire Department. His namesake, Patricia Flynn, a niece born after he died, traveled to East Hampton just for the occasion and read excerpts from his letters home.

He never wanted to join the Army, his letters to his family revealed when they shared them with The Star in June of 1968. “I don’t agree with it myself,” he wrote in one letter, though he grew proud to be in the infantry.

In a Jan. 28, 1968, letter to his older brother, Richard, he wrote, “You see, I’m really quite shy about going to Vietnam. I think I’ll make it but if I don’t, I don’t want to have had my life wasted on another Korea.” A few sentences later, he added, “Don’t think I’m a coward, because I’m not afraid to fight.”

In a letter he wrote to his mother after arriving in Vietnam, he admitting to be afraid, “but it’s not the kind of fear you feel at home. It’s like you’re just afraid of not being able to do your job right. Don’t get me wrong though, I’m afraid of dying too.”

His confidence grew in the weeks he was in Vietnam. In an April letter he said, “You know it’s funny, God only knows how much I didn’t want to come over here, but now that I’m here I don’t think I would leave if I got the chance. You’re treated like a man over here and all the sergeants and other higher officers tell you straight. They say that we’re not fighting for God and country, we’re fighting to stay alive so we can go back to the world and live like a human being again.”

In a letter to his brother around April 22, he wrote about how the death of a man called Doc, “our medic a very good and close friend,” led him to think about his own death. He told his brother he wanted “a joyous funeral.”

“Don’t ever be sorry I died over here because I’ll have died like a true man. Sure, shed a few tears, but after the funeral I want all my friends to get very drunk. And most of all I want you and them to be proud of me,” he wrote.

“I am proud of him,” Mr. Bye said when read his friend’s letter. “He was a good friend. I always thought we would get together again,” he said, adding the two had talked about meeting in Australia if they could get leave after they both served in Vietnam.

Prudence Carabine, a member of the class of 1966 with Private Flynn, remembered him as “a good guy” with an artistic streak. “I don’t think the war at that point, when we graduated, had really hit us in our senior class, and then he went off and died,” she said.

She lost her brother, David, two years later in an accident coming off his tour in Vietnam (he was not listed as a casualty of war). “Unfortunately, I wrapped Pat and David up in the same ball of emotion,” she said. “The realization when Pat died, to all of us, was that this was serious business and there were a lot of questions about it.” She would later demonstrate against the war with the Students for a Democratic Society.

While the Legion and the V.F.W. has honored Private Flynn for the last 50 years, Ms. Carabine and her husband, Brian Carabine, a Marine who served in Vietnam and the quartermaster at V.F.W., said they are both thankful that Private Flynn was recognized in a public place.

“I think that John and Bill and Sid kept pushing on it and talking to everybody. They organized getting the stone from Bistrian’s. They had it delivered and put in place with help from Scott Fithian from the village. They got a generous donation for the plaque from the man who owns Buoy One (Robert Pollifrone),” Mr. Carabine said.

It came together quickly, Mr. Mott said. “We went from nothing in April or so to this day,” he said, adding that the Legion paid for one bench and the V.F.W. for another.

“It was a great coordination between civic organization and municipalities,” Mr. Lys said. “It was a long time coming.”