Marital States

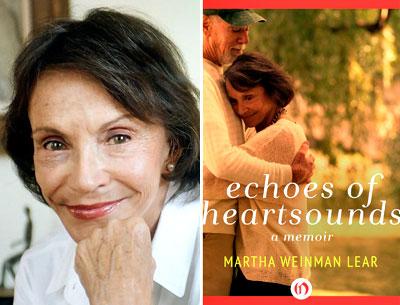

“Echoes of Heartsounds”

Martha Weinman Lear

Open Road, $9.99

Martha Weinman Lear’s new book, “Echoes of Heartsounds,” directly evokes her riveting, unsparing memoir “Heartsounds.” In the earlier work her husband, Hal, a beloved doctor, had a massive heart attack, followed by complications that led to his death at 57. The irony is not lost on Ms. Lear when, 30 years later, she has a coronary and ensuing infection and finds herself in the same hospital ward with the same attending physician.

Although she finds kindred spirits among many of the medical professionals, she is also afflicted with some of the same ignominy, the coldness, the cruelty that assaulted her first husband. Of course she is terrified that her outcome will be the same as her husband’s. But despite the parallels, Ms. Lear is far too clever and introspective a writer to be content with comparing and contrasting two myocardial infarctions.

“Echoes” is really a book about marriage, about long-ago widowhood, and about the “marriage” within oneself of former and present spouses, and the delicate balance that goes on within one’s soul as one honors the first spouse while loving the one who is present. Long after Hal’s death, Ms. Lear fell in love with and married Albert Ruben, a screenwriter.

One evening after eating mushroom barley soup, Ms. Lear becomes quite ill. It couldn’t possibly be the soup — she’d made it herself the night before. Albert speaks to her doctor, who maintains that vomiting is not a symptom of a heart attack but encourages Ms. Lear to go for an EKG the next day. The test reveals that something has happened, and a birthday trip she and Al were taking to Charleston was immediately canceled.

Shortly after she is admitted, Ms. Lear says she’s feeling fine and Al comes to the hospital, loops his arm through hers for a walk, and suddenly “everything turned surreal. Everything was powered by the most vivid sense of having been there before.” Ms. Lear feels she’s “tripping into Hal’s coronary and he into mine, even as I walked there with Al, oh, it was all so weird, and I knew that I was conflating the two men, both beloved, apart from my father the only men I ever truly loved, confusing them now in that strange and discomforting way, joining myself now with the one and then with the other, and their own images floating into and out of each other.”

Ms. Lear describes how she and Al had walked on West 86th Street shortly after they’d met, strolling hand in hand, knowing they were about to embark on something “serious.”

Transitions and the back story are an important part of this memoir. Years before, when Ms. Lear first decided to move into Al’s Central Park West apartment, “those first months were not easy. We were both out of the habit of compromise, flexible as a pair of wooden yardsticks.” And then Al asks Ms. Lear if he should take down the photos of the life he led with his wife Judy, who had died, their children, their grandparents. And rather than erase his past, they kept the photos and added her family photos, her grandparents’ and parents’ wedding portraits, and, as she points out, the photo of her wedding to Hal hung close to the photo of Al and Judy’s wedding. Those photos were joined by the “Al-and-Martha pictures,” representing a richer, fuller set of lives.

Ms. Lear’s comment is so original and so astute: “It may be love that makes the world go round, but continuity is what keeps it on its axis.”

But flash forward to the hospital: Things have grown much worse. Ms. Lear develops a staph infection that causes delirium and requires heavy-duty antibiotics. Days later as she’s coming to her senses and desperately wants to leave, she learns she has three choices: Return home (the antibiotics alone would be $500, never mind the astronomical cost of aides), stay in the hospital, or check into a nursing home.

She recounts a visit to a friend who’d gone to such a facility “to recover.” The portrait is bleak: “I had seen him there, seen the elders slumped catatonic in their wheelchairs lining the corridor walls, seen him visiting among them, head in his hands, staring into some grim personal space, smelled that odor — that characteristic ineffable odor of such places, attar of dust, decay, urine, grief, fear, hopelessness, eruptions of gas, exhalations of bile, floor wax, room fresheners (carnation, lavender, lily-of-the-valley), ammonia cleaners, astringent sanitizers — and I had thought, Oh, sweet Jesus, if sickness isn’t enough to finish a body off, this place could do it.”

The hospital staff encourages her to stay put. But Al wants her home. Again Ms. Lear uses her knowledge of the marital state and its intersection with the human condition for an observation. “ ‘Let’s sleep on it,’ [Al] said, which is what you always say about the indecisions that will keep you sleepless.”

In the end she remains in the hospital, and because she is “bad enough,” the physiotherapy department allows her admission to its special program — the aftermath of the staph infection gave her the leg up. On its own the heart attack wouldn’t have been “bad enough” to warrant the therapy. But the staph has provided her with the jobs of relearning to walk, to understand the mechanical requirements of getting in and out of cars, and of bathing and dressing. Even making a cup of tea becomes a task of gargantuan proportions.

But as I said, this is really a memoir about marriage. One of the book’s most poignant scenes falls between Hal’s death and Ms. Lear’s meeting Al. In a flashback she recalls driving on the Long Island Expressway when a tire blew; she over-steered and ended up spinning. Astonished to be alive as she emerged to the gawking of rubberneckers, she felt she had to get to a pay phone to call her husband, Hal. “But wait. Some problem here . . . I can’t call Hal. Hal is dead.”

She had in that instant “the most piercing sense that this was what marriage meant: Marriage meant that there was someone in the world whom you must call — not those whom you may call, not the relatives and friends who hold you dear and who would grieve if you were gone, but the one person, even if, let’s say, you do not hold each other so dear, the one person whom it would be unthinkable not to call — a matter of basic domestic civility, like calling to say that you won’t be home for dinner — and to whom you say, ‘Listen, I was almost killed on the Long Island Expressway but I am all right and not to worry and I will be home soon.’ ”

In the end the greatest task for Ms. Lear is to persuade the ghost of her first husband, Hal, to recede and let her resume her current life. There is a pull and push throughout the hospital stay as Ms. Lear bravely reveals her petulance with Al. But then she is able to return home in time for Thanksgiving dinner, surrounded by present family. Still recuperating, but with a renewed, vibrant inner voice: “Continuity, it said.”

Martha Weinman Lear lives in New York and East Hampton.

Laura Wells regularly contributes book reviews to The Star. She lives in Sag Harbor.