Out of the Cornfields

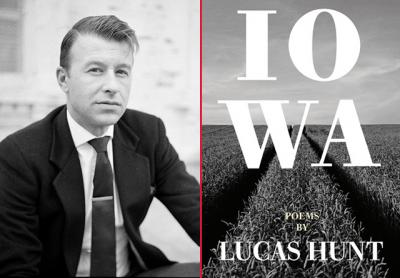

“Iowa”

Lucas Hunt

Thane & Prose, $21.99

Lucas Hunt’s new book of poems, “Iowa,” is a somewhat uneven collection that shows the poet engaging his subject matter through use of precise evocative imagery, while other poems — notably his shorter ones — fail to engage because they neglect to provide readers with surprise or illumination. So there is much to admire in this collection and much one wishes Mr. Hunt had further revised.

The physical book itself seems something of an anomaly; poems are printed on the recto pages only, an affectation that belies the poet’s simple, honest, and direct statements. Rear cover copy informs the reader that this volume is “the first of five books in an autobiographical collection of cinematic poetry.” This reader hopes the poet will improve upon his work by adding poetry to what is only cinematic.

What does this mean? Too many of Mr. Hunt’s shorter poems seem to lack poetry’s transformational energy, never leaving behind the literal or the cinematic for the figurative. Here, for instance, is “Walking” in its entirety:

With dogs on a gravel road

dust from passing

truck plumes

into a cloud over

the soy and corn fields.

Obviously, the title is meant to be read as part of the poem’s sentence. But what is the point of a poem that offers only an observation? Where is the poetry? Yes, the poem offers an image, and one may argue it offers an image as practiced by Williams and Pound. But this type of Imagism lacks the touch of modernist ambiguity or figuration found in Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow” or Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro.” What would the Williams poem be without the ambiguity of “So much depends / upon”? What would the Pound poem be without the final metaphor of “petals on a wet, black bough”?

In another short poem, “To You,” Mr. Hunt tries to add the figurative but confuses his reader. Here it is:

Suspended hair feathers

wave like leaves;

nature’s hand

applauds in the trees.

Here, Mr. Hunt unsuccessfully mixes his metaphors. First, hairs are not feathers; second, it takes two hands to applaud, unless, of course, Mr. Hunt is using “hand” in its meaning of to applaud, as in “let’s give him a hand,” which, of course, would make the verb “applauds” in the final line a redundancy. East Hampton’s own Allen Planz used to say at his readings that short poems were more difficult to write than long poems; I’m inclined to agree.

This reviewer also noticed a number of poems in which Mr. Hunt uses punctuation inconsistently or commits a number of grammatical or mechanical inconsistencies. Mr. Hunt needs to be more careful in his use of language, as every poet must. I’d be remiss if I didn’t call him out on these failings. True, some readers may accuse me of being too fastidious, but poets — especially poets — need to honor their language and its rules because mistakes detract from the work’s efficacy.

The poem “Tornado,” for instance, contains several errors, including “In nearby towns, or farther off, / A city candidates visit to get the vote.” What’s needed here? For the article at the beginning of the second line to disappear or for the poet to add an apostrophe and an s after city? Later in the same poem, Mr. Hunt writes, “Hits someone on the head and blood / soaks their face, / they run for cover . . .” I’m not maintaining that civilization will collapse (it hasn’t yet!) as a result of faulty pronoun agreement, but the rules exist for a reason. I also don’t get the sense that the rule is violated on purpose to mimic the voice of a speaker who doesn’t understand that “someone” is a singular pronoun and doesn’t agree with “their” and “they.”

As for punctuation, poets may decide to dispense with it entirely or use it to influence rhythm or use it as a grammarian might. Whatever choice a poet makes, readers will wish that the poet would follow his choice consistently, at least within each individual poem. In “Calling,” Mr. Hunt confounds this reader with his inconsistent comma usage. Here’s the first stanza:

Lake borne urges come to fruition

ripe watermelon juice down

both cheeks, pink rinds

smile from a sink a friend

calls late at night to talk about love.

Clearly, Mr. Hunt has decided to use commas in this poem, and in this first stanza we note the comma as caesura after “cheeks.” Perhaps Mr. Hunt has chosen to disregard the use of commas at the end of his lines; one would expect a comma, mechanically speaking, at the end of line one. Poets, however, often employ line breaks as commas, a contemporary convention. But Mr. Hunt does use the interior comma; so why include a comma after “cheeks” but not after “sink,” where another comma is expected to separate the two images? This inconsistency occurs elsewhere in this poem and in other poems in this collection and is simply maddening.

But I’m done playing the stuffy pedant with his picayune complaints. Mr. Hunt has a real eye for the apt image. The book is chock-full of effective imagery. The book’s third poem, “Cornfield,” recreates on a blank white page the complexity of a field, with its energies and subtleties, in a distinctly sensuous way. A single sentence broken over nine lines, here’s the poem in its entirety:

Emerald waves applaud midsummer’s

undulant hills, honeyed kernels,

amber tasseled stalks inert,

wind-wisped leaves stir earth’s aroma,

slow circling suspensions of time transpose

a dust blown cloud, adagios of air,

granular infinitudes above

a gravel road, long grassy ditch lined

with barbed wire fence that goes nowhere.

This poem is worth our time and scrutiny. It’s not only the cornfield that Mr. Hunt skillfully recreates here but also the sense of open space above and around it. The poem’s first line conveys motion and metaphor. The poem is rich in visual imagery and interesting diction (“granular infinitudes”). The language is fresh, the picture is clear, and the poet utilizes effective closure — the fence that goes “nowhere” offers a counterpoint to the image of the field and the space above and around it in slow, perpetual movement.

Even Mr. Hunt’s use of “inert” in line three seems apt; my dictionary defines this word as “not having the power to move itself.” So, while the field appears to sway, the ears of corn will not move unless another agent — like the wind — acts upon them. Readers smell the earth in line four, and the addition of a term of musical direction, here made plural, “adagios,” bolsters the sense of movement and auditory imagery within, around, and above the cornfield.

Immediately following “Cornfield” is “70th Avenue,” another strong poem dependent almost entirely upon imagery. But Mr. Hunt put this poem together without wasting a word. He also includes unexpected verbs, as poets must, and the verbs in this poem elevate the poem out of mere descriptiveness to the figurative level that distinguishes poetry from prose. The lines that simply describe place us firmly in the Midwest and are often fragments, like the opening two lines: “Barbed wire fences / overgrown with weeds.” But the poem’s final two lines rescue the rest of the poem from the mundane: “Fields roll under power lines / and harvest the sky.” That’s lovely closure, especially Mr. Hunt’s use of “harvest.” We expect the field to be harvested, but here the field performs the action of the verb, and this seems both true and new.

Many other poems like this exist in this collection, including “Dollar an Hour,” “Hired Hand,” “The End,” “Leaving the Farm,” and “Buena Vista Road,” just to name a few. These poems are economical, descriptive, and employ interesting metaphors or use verbs in surprising ways.

A favorite poem is “Cicadas.” Here Mr. Hunt employs wonderful poetic music, which is too often, in this reviewer’s opinion, missing from this collection. Mr. Hunt mines a wider vocabulary here for its sonic properties. The imagery is as precise as in “Cornfield,” but in this poem form and content most effortlessly merge. After all, this poem concerns the cicadas’ sound, a “unisonic / hum,” and Mr. Hunt uses alliteration, assonance, and consonance most effectively. This poem, therefore, seems to bristle with energy. It’s a pleasure to read multiple times, especially aloud.

I’m hoping Lucas Hunt will hone his editorial eye and begin to write short poems that will rise above the banal to surprise and engage as well as some of his longer poems do in “Iowa.” I’ll be watching for new work from him to gauge how he improves. With a talent like his, there’s no doubt he will.

Dan Giancola’s books of poems include “Part Mirth, Part Murder” and “Songs From the Army of Working Stiffs.” He teaches English at Suffolk Community College.

Lucas Hunt, formerly of Springs, is the author of the collections “Lives” and “Light on the Concrete.” He will read from “Iowa” at Harbor Books in Sag Harbor on Sunday at 5 p.m.